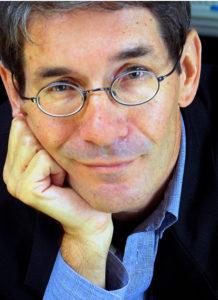

A series of informal, intimate talks given by literary and cultural luminaries, In Conversation with the Rosenbach delves into fascinating histories, intellectual curiosities, and inspiring ideas. Each program offers the audience a chance to join the conversation after the talk and share their own thoughts and questions. Join us March 23 to hear book columnist Michael Dirda and Rosenbach programs manager Edward G. Pettit discuss the storytelling of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Rosen-blog: You’ve been called the “the best-read person in America” (by The Paris Review) and most of your publications address a wide range of literature; On Conan Doyle is your only book about a single author. What makes Sir Arthur Conan Doyle stand out among the classics?

Michael Dirda: If you visit used bookstores, you’ll often see a shelf or case labeled “Books on Books.” Everything I’ve written could be filed under this category. My very first publication was a paperback, written for the Book of the Month Club, titled “Caring for Your Books.” “Readings” is subtitled “Essays and Literary Entertainments.” “An Open Book” is a memoir of how reading shaped my early life. “Bound to Please” collects my more serious pieces on world literature. “Book by Book” derives from quotations and passages in my commonplace book. “Classics for Pleasure” got its start as an expansion of Clifton Fadiman’s “Lifetime Reading Plan” and “Browsings” gathers a year’s worth of weekly essays I contributed to The American Scholar’s homepage.

As you rightly say, “On Conan Doyle” is the only one of my books focused on a single author. It came about this way. Princeton University Press has a series called “Writers on Writers,” short books of about 200 pages in which a poet, novelist, or critic reflects in a personal way on a favorite writer. When I was asked whether I might want to write one of these little books, I suggested Montaigne or Stendhal, from among classic authors, or Russell Hoban, from among living writers. But when I happened to mention I was a member The Baker Street Irregulars, the people at Princeton immediately counter-proposed Arthur Conan Doyle.

I could see why. Conan Doyle would be a fresh, unacademic choice. I’d bring to bear unusual knowledge, since I was part of the BSI, a celebrated but slightly mysterious organization. Most of all, though, the book could ride the flapping coattails of Robert Downey Jr. and Benedict Cumberbatch (the Jonny Lee Miller “Elementary” hadn’t started yet). So I wrote the book fairly quickly and Princeton brought it out just about the time the second –or was it the third?–season of the BBC “Sherlock” was being aired.

Of course, Conan Doyle was also a remarkable writer, in multiple ways. The editor of The Strand magazine called him the greatest natural-born storyteller of the age, rivaled, I think, only by Kipling and the young H.G. Wells. He wrote every sort of book—historical swashbucklers (“The White Company” “Sir Nigel”), light serio-comic novels (“Beyond he City,” “A Duet”), supernatural fiction (“The Parasite,” “The Horror of the Heights”), fantastic adventures (“The Lost World,” “The Poison Belt”) and much else, including poetry, essays, travel books, spiritualist tracts and even pirate tales (the excellent “Dealings of Captain Sharkey”). Almost all these are worth reading, so there was a whole body of work I could talk about, much of which has been overshadowed by the Holmes stories.

RB: On the basis of “the whole art of storytelling,” what is your favorite Sherlock Holmes screen adaptation?

MD: I think Basil Rathbone’s “Hound of the Baskervilles” and “Adventures of Sherlock Holmes”—the first two of Rathbone’s many movies about the detective—are still terrifically entertaining and well done. But Nigel Bruce is a bumbling dolt, which the real Watson wasn’t. In fact, it’s the Watsons—Edward Hardwicke, Jude Law, Martin Freeman, Lucy Liu– who have made the modern screen adaptations of the stories so much better than the older treatments.

The Jeremy Brett adaptations are probably the most faithful to the originals and I very much enjoy them still. The Robert Downey Jr. films are certainly exciting, but they’re really steampunk adventures. Jonny Lee Miller is constrained by the hour limit of commercial television, but I enjoyed the first two seasons of “Elementary,” even if I gradually drifted away from it. I’m among those who feel the BBC “Sherlock”—after the first two seasons—grew too mannered and too clever by half. It was always fun to watch— Cumberbatch and Freeman are wonderful actors and I could never get enough of Andrew Scott’s Moriarty—but the plots moved too far away from the Holmes stories for my taste and became rather indulgent and show-offy.

RB: You’ve been an active member of the Baker Street Irregulars since 2002, joining a number of literary luminaries past and present. Are there any good stories you can share about the group’s activities?

MD: There are many I might tell, but I should probably save them for my Rosenbach evening. Perhaps what is most notable about the Baker Street Irregulars is that its members are remarkable not just for their knowledge of, and passion for, the Sherlock Holmes canon. The 300 or so invested Irregulars—that is those who have been given a canonical name, called an investiture—include one of the country’s leading cardiologists, a former CTO of Apple, the owner of New York’s Mysterious Bookshop, the writers Nicholas Meyer, S.J. Rozan, Lyndsay Faye and Neil Gaiman, a distinguished curator of rare books, a retired Pentagon strategist, a well known film and TV actor, a leading Hollywood tax lawyer, several librarians, many lawyers, a museum director and people from England, Switzerland, Japan and other countries.

RB: As you note in your book, the Sherlock Holmes stories comprise only a fraction of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s oeuvre. Is there one other work by this author you wish were more widely read?

MD: After the Sherlock Holmes stories, Conan Doyle’s most-read book is “The Lost World,” an account of an expedition led by the irascible Professor George Edward Challenger and the eventual discovery of a Central American plateau inhabited by . . . well, I won’t say. That book, though, is quite well known, as is its first sequel, “The Poison Belt.” After these, I would recommend the swashbuckling short stories gathered in “The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard” and “Adventures of Gerard.” In them an old Napoleonic hussar reminiscences about his youthful escapades, which are, by turns, exciting, romantic and comic. They are among the best historical short stories ever written.

RB: What’s your favorite book or object at the Rosenbach?

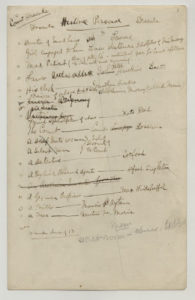

MD: Since I’m working on a book about British popular fiction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, I suppose the draft of “Dracula” is the item that is of most interest to me just now. That said, I’m also a member of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America and a fervent admirer of Dickens and Conrad, so I’m also drawn to the Rosenbach’s manuscript holdings of their work.