Years ago as an undergraduate student of literature, I ended up in a class that focused solely on the work of William Blake and I wasn’t exactly thrilled about it. I had just discovered the vivid trove of Latin American magical realism and the last thing I wanted to spend my time reading was the antique poetry of an English romantic. Blake’s tyger just didn’t burn brightly in The Norton Anthology, the only place I had ever encountered his work. Of course, a semester spent studying his illuminated engravings upset all of my assumptions. I walked away with a profound appreciation for the book as a physical object and with a curiosity about the nature of interpretation, particularly the question of what distinguishes the act of looking from that of reading. My work as a collections intern at the Rosenbach has provided me with a wonderful opportunity to really steep in these issues.

I’ve always felt that books are magical things. As anyone who has helped me move between apartments will tell you, I’m reluctant to let go of a book once it has found its way into my personal library. I’ve never been one to keep a diary but I do feel that my collection of books amounts to something like that. The notes I scribbled in the margins of Pride and Prejudice at the age of 16 instantly bring me back to certain cringe-worthy experiences that led me to some interesting interpretations. Each book in my library is a little portal that allows me to regain access to a particular time in my life. The stacks amount to a museum of past impressions.

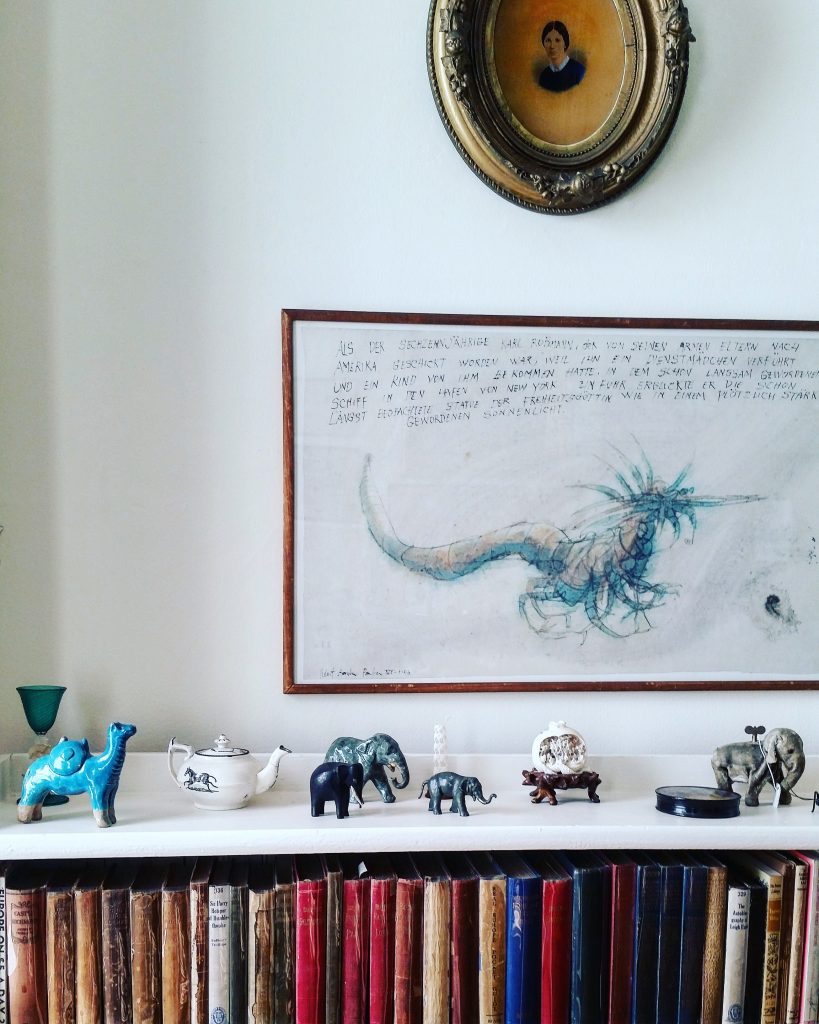

Recently, the registrar and I have begun an inventory of the Marianne Moore collection. Moore was one of the great Modernist poets, drawing admiration from the likes of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. In 1969, the Rosenbach purchased her personal and literary papers. A couple of years later, Moore bequeathed the contents of her living room to the museum which were later reassembled to carefully mirror the layout of her Greenwich Village apartment. Moore herself was something of a magpie collector. She saved almost every scrap of ephemera she came across resulting in a collection that includes diaries, magazine and newspaper clippings, postcards, letters, and more than two thousand books. Various knick-knacks and furnishings — a footstool from T.S. Eliot, a painting by E.E. Cummings, a baseball signed by Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle — come together to convey a particular moment in history with a great sense of intimacy.

Working our way through the collection, we’ve come across such seemingly banal objects as handkerchiefs, rubber bands, and pens that all have accession tags attached to them. Essentially, we’ve been rooting around in a deceased woman’s junk drawer, making certain that all of the contents are there and in good repair. All of this has had me thinking: why do we conserve, collect, and exhibit these objects? Ultimately, I think their value lies in their fragility. This quality serves as a reminder of our own mortality. It is this delicate transience that gives the book, the letter, and even the rubber band the ability to convey difficult emotive knowledge.

During a 1951 radio interview, Moore was asked about what inspired her to write. She replied, “Books, conversation, a remark, objects, circumstances, sometimes make an indelible impression on one, and a few words which occurred to one at the time the impression was made, remain associated with the original impression and suggest other words.” Students of Moore would do well to spend time with this very special material archive.

Leah Comiskey is a Collections intern at the Rosenbach. She is currently pursuing a master’s degree in museum education at the University of the Arts with research interests in contemporary art and postmodern literature.