“I have known men to hazard their fortunes, go long journeys halfway about the world, forget friendships, even lie, cheat, and steal, all for the gain of a book.”–A.S.W. Rosenbach, Books and Bidders: The Adventures of a Bibliophile (1927)

In January of this year, the book world was shocked by a daring theft from a rare book warehouse in London. The thief or thieves apparently bypassed security measures by entering from the roof, drilling holes in the warehouse skylights and rappelling about forty feet down on ropes. Around 160 rare books were stolen–including works by Dante Alighieri, Leonardo da Vinci, and Galileo Galilei–totaling more than £2 million. Experts on the scene posited that it was a crime of opportunity, but the precision and sophistication of the hit prompted speculation that the theft was commissioned by a private collector–the media began calling this hypothetical collector “The Astronomer.” Those responsible have not yet been captured, but public imagination certainly was.

Thanks to our exhibition Clever Criminals and Daring Detectives, we’ve been enjoying a summer of books about crime, but we haven’t encountered quite so many crimes about books. While art theft gets a glamorous fictionalization in films from the Thomas Crown Affair to Muppets Most Wanted, and most crime buffs can name at least a few major paintings that were “artnapped” (such as the Mona Lisa), book theft doesn’t usually get such a high-profile treatment in media. Nonetheless, rare book history is speckled with a few shady characters with nicknames as colorful as “The Astronomer”: Stephen “The Book Bandit” Blumberg, who stole around $5 million worth of rare books from libraries across America for his own use; William “Tome Raider” Jacques, who was found with a substantial list of books he had already stolen or intended to; John “The Man Who Loved Books Too Much” Gilkey, whose exploits were chronicled in a book by the that title. With few exceptions–such as Forbes Smiley, who sliced maps out of library atlases and sold them to collectors–most notable biblioklepts did not steal for financial gain but for personal use. Indeed, a few of history’s book thieves were diagnosed with a condition called bibliomania, which indicates an obsession with book collection to the point of jeopardizing personal relationships or health.

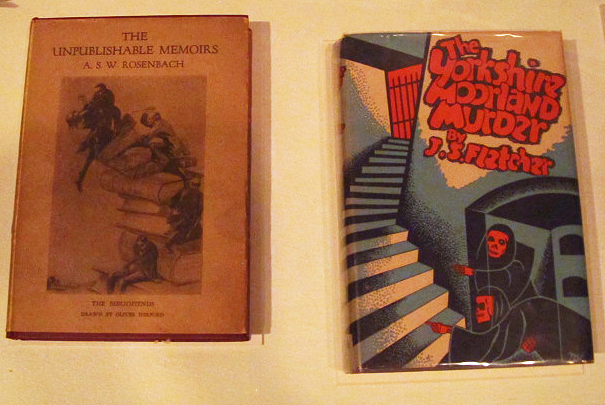

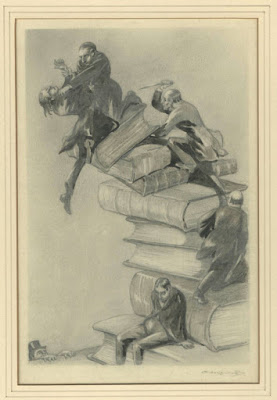

Dr. A. S. W. Rosenbach certainly knew a thing or two about “the gentle madness” (as author Nicholas Basbane dubbed bibliomania) and its illegal counterpart. As a dealer who bought and sold rare volumes for collectors, Rosenbach himself had a passion for acquiring important books and learning their fascinating histories–and as noted in the epigraph above, he met several others who would go even further. In 1917, he published a volume of stories about a book collector, Robert Hooker, who lacked the funds to finance his desire for rare volumes. The opening story in The Unpublishable Memoirs involves a highly-coveted eighteenth-century book (the titular memoirs) which Hooker attempts to buy, but he is outbid by a richer and more ostentatious collector. The lucky buyer’s gloating is short-lived, however, as Hooker finds a way to relieve him of this priceless volume and claim it for his own library. Like many of history’s biblioklepts, Hooker’s origin story is rooted in a desire to possess books rather than wealth, but the character’s dabbles with forgery and theft made some contemporaries wonder just how Rosenbach knew so much about book-related crimes.

But it was years after the publication of both Memoirs and Books and Bidders that Dr. Rosenbach would have a close encounter with an organized ring of book thieves. As told by rare book curator Travis McDade in The Thieves of Book Row, the rare book trade in America flourished in the 1920s, accompanied by soaring prices and competitive auction, and glamorous style section coverage of collectors and dealers (of which Dr. Rosenbach certainly had his share). The Great Depression saw these profits plummet, but book crime began to climb–particularly targeting universities and public libraries. Some of these priceless tomes have never been recovered, but a dedicated investigator named G. William Bergquist was able to pinpoint some of the key players in the book thieving trade and reclaimed some of their loot. Of the bibliocriminals Bergquist tracked, one of the most surprising figures is a man called William Mahoney, who assisted a ring with the uninspired name of “the Romm Gang.” Mahoney not only associated with biblioklepts but recruited them, and was responsible for targeting a number of the east coast libraries that were hit. Yet evidently Mahoney had a real feeling for rare books; when Bergquist tracked him down, rather than arresting him on the spot, he actually invited him to a nice dinner with a number of book trade luminaries–including our own Dr. R. Perhaps this dinner offered William Mahoney a turning point; he turned his life around, got a job at the Newark Public Library, and assisted G. William Bergquist in investigating and tracking down book crime throughout the 1930s. His story is almost the opposite of Dr. Rosenbach’s 1927 quote–Mahoney certainly did lie, cheat, and steal for the gain of a book, but he was also willing to forgo all those activities to protect a precious collection.

You can see Dr. Rosenbach’s The Unpublishable Memoirs as well as a Dr. Rosenbach-inspired mystery, The Yorkshire Mooreland Murder, on view in Clever Criminals and Daring Detectives through September 1. We just ask that you leave them where you find them!