April 2 is International Children’s Book Day–a day you might well celebrate with a visit to our exhibition of books bequested to the Rosenbach by Maurice Sendak, which include some remarkable rare editions of books by Beatrix Potter, Margaret Wise Brown, and the brothers Grimm as well as the marvelous movable circus book by Lothar Meggendorfer.

Maurice Sendak once famously said “I don’t believe I have ever written a children’s book”–a statement which begs the question of what makes a book “for children” in the first place. After all, theories about childhood education and development are always changing. Today we usually consider books appropriate for a certain stage of childhood if the text is written at a specific reading level, the themes or conflicts mirror a child’s development, and the illustrations are eye-catching and evocative. But what about books that are written by authors better known for their books for adults? The following books are written or edited by authors from our collection whose most famous writing may be considered difficult, intellectual, even–in some cases–inappropriate for children!

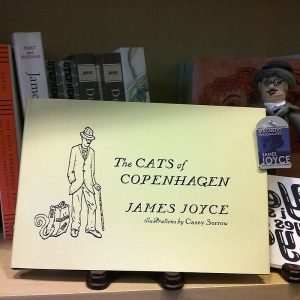

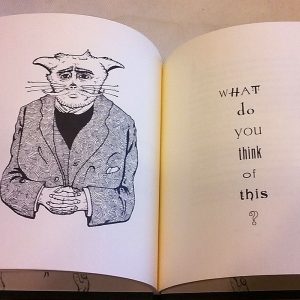

James Joyce, Cats of Copenhagen. This odd little book was not conceived as a book for children generally; its text was taken from playful letters written by Joyce to his grandson, Stephen James Joyce, and was not published until Joyce’s writing entered the public domain. Its whimsical illustrations and creative typography were therefore not explicitly part of Joyce’s creative vision, but seem well-suited to the very suspicious behavior of the inhabitants of Copenhagen, who are definitely not cats. This book is available for purchase in our museum shop.

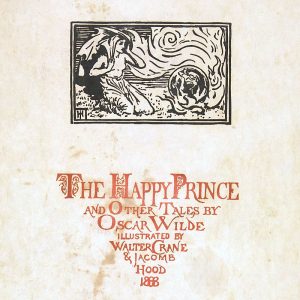

Oscar Wilde, The Happy Prince and Other Tales. Continuing the theme of “Books for children written by adults whose books were banned for obscenity,” Wilde’s collection of fairy tales was first published in 1888 with illustrations by Walter Crane. The stories invoke the romantic figures of princes and princesses, magical flowers and gems beyond price, and the broad emotional categories (happiness, selfishness) which are characteristic of many traditional fairy tales. These characteristics might also be said to anticipate the allegorical, magical elements of Wilde’s 1891 story The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Our copy of The Happy Prince was bequested to the Rosenbach by Maurice Sendak; it is not currently on display.

Detail of The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde. Illustrated by Walter Crane and Jacomb Hood. London: Published by David Nutt, 1888. Collection of the Rosenbach.

John Ruskin, The King of the Golden River. John Ruskin was a prolific writer and thinker whose theories left their mark in many arts and sciences–painting, architecture, politics, and on and on; students of art history may know him best as the critic who defended the unconventional art of J. M. W. Turner and Pre-Raphaelite painters. Victorian children might have known him best, however, as the author of a cautionary fable featuring winds who turn into men and men who turn into rocks.

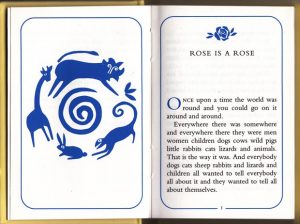

Gertrude Stein, The World is Round. Margaret Wise Brown, who authored the two fuzzy editions of Little Fur Family currently on display in the Recent Acquisitions exhibition, is probably best known for writing Goodnight Moon. But Brown also edited and published children’s stories by other authors. In the 1930s, she conceived of a series of children’s books written by celebrated authors of literary fiction. Not many took her up on the offer, but surprisingly, the famously avant-garde poet Gertrude Stein responded that she had already drafted a children’s book and was ready to publish. That book became The World Is Round; the chapter pictured below seems to echo one of Stein’s most famous quotations, “A rose is a rose is a rose.”

There are many more fascinating examples, including two poets and friends of Marianne Moore–Langston Hughes and e. e. cummings–who published books for children entitled The First Book of Jazz and Fairy Tales respectively. But Maurice Sendak’s point is made: perhaps some stories are written to be good for children, but good stories are written for everyone.