This post was cross-posted at the Free Library of Philadelphia blog, where our affiliates have been celebrating their One Book One Philadelphia selection, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time.

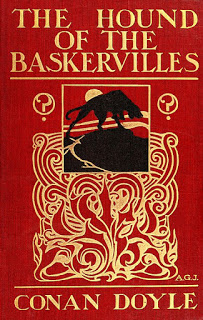

In The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Christopher Boone’s investigation into the death of a neighborhood dog is inspired by his love of detective fiction. In particular, he is an avid fan of Sherlock Holmes, whose legendary powers of observation help make Christopher proud of his own ability to perceive and remember details that would be missed by most. But the adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson also help Christopher make sense of surprising or difficult things that happen to him as he gets closer to solving his own mystery. He motivates himself to travel alone to London by reminding himself that Holmes and Watson stop for lunch at Swindon when they are traveling by train in “The Bosombe Valley Mystery” (131). Christopher occasionally struggles to recognize emotions other than happiness and sadness, but he is able to recognize and respond to the sensation of fear thanks to these stories: “I felt my skin… cold under my clothes like Doctor Watson in ‘The Sign of Four,’” he observes (135). Christopher’s favorite book is The Hound of the Baskervilles, a Sherlock Holmes adventure in which dogs both real and imaginary play a crucial role in the mystery plot, just as they do in Christopher’s own story.

The Hound of the Baskervilles occupies an unusual position in the world of Sherlock Holmes, and its popularity speaks volumes about what makes Sherlock Holmes appealing both to Christopher and the world at large. This book is one of the only novels Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about Holmes; most of the master detective’s adventures are published as short stories. Also, The Hound of the Baskervilles was first serialized in 1901, which is close to ten years after Doyle publicly and controversially killed off his beloved creation in an 1893 short story titled “The Final Problem.” The Hound of the Baskervilles was written as a sort of prequel—a throwback to the early days of detection before Holmes perished in mortal combat with his nemesis Moriarty—but Doyle eventually resurrected his creation in yet another set of short stories in 1903.

Why would Doyle kill off his most famous character, only to bring him back to life? In his own interviews and autobiography, Doyle is careful not to say; fans can only speculate. Sherlock Holmes made Doyle one of the highest-paid and most famous authors of his own time; perhaps money or celebrity lured him back, or pressure from multitudes of fans who sent letters to 221 Baker Street as though it were a real address. But Doyle also wished to write in other genres of literature—plays and historical romance, which he considered to be more serious fiction, although his publications in that genre never picked up much steam. “I do not wish to be ungrateful to Holmes, who has been a good friend to me in many ways,” Doyle wrote in his 1924 autobiography; “If I have sometimes been inclined to weary of him, it is because his character admits of no light or shade. He is a calculating machine” (Memories and Adventures 92). Yet one might argue that the machine-like abilities of Holmes are part of what makes him so appealing as a character. He is aspirational: his powers of detection and deduction are beyond most of us, but as we watch him solve the mystery, we can glimpse those powers. For Christopher, who sees himself in Holmes’ powers of logic and perception, the master detective is a model of bravery and survival.

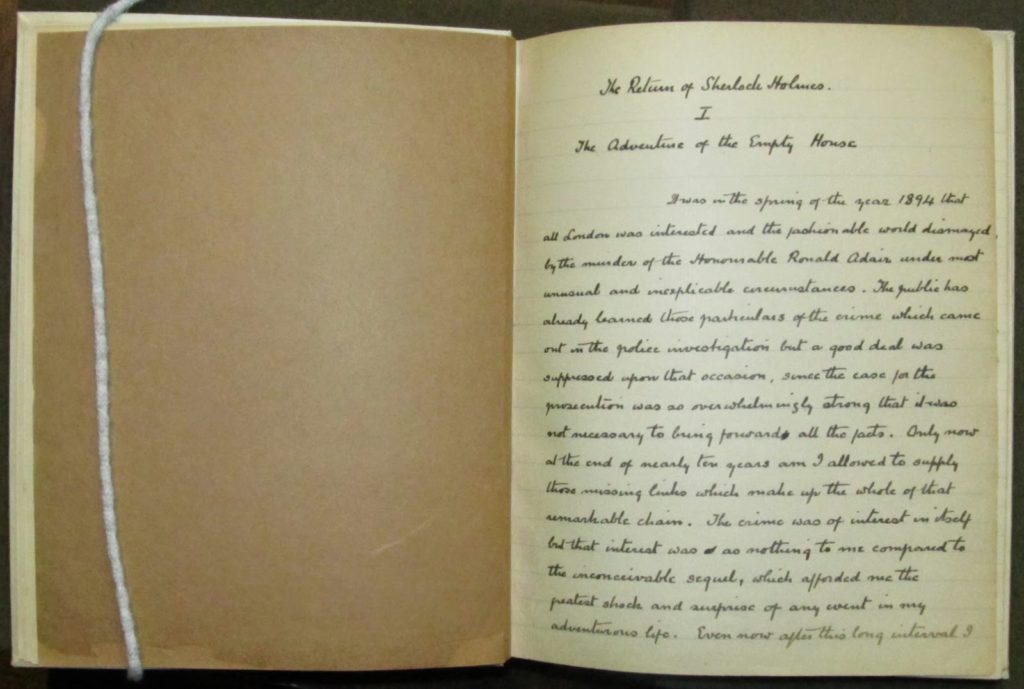

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle may not have been able to see the enduring literary appeal of Sherlock Holmes in his lifetime, but other book lovers and collectors certainly did. After Doyle’s death in 1930, Dr. A. S. W. Rosenbach purchased Doyle’s “crime library” and the Rosenbach collection also includes Doyle’s hand-written manuscript of “The Adventure of the Empty House,” the story in which Sherlock Holmes reappears and explains that he didn’t actually die at Reichenbach Falls, just found it convenient to pretend for a while. Indeed, by popular demand, Sherlock Holmes has continued to live on page and screen in the century since then.

“The Adventure of the Empty House,” along with other related objects, will be on view during The Rosenbach’s Clever Criminals and Daring Detectives exhibition next spring.