Your husband flees to another country after Mary Tudor becomes Queen of England. When he goes, he tells another man to “look after” you. Thirty years later, you have a Renaissance poetry stand-off with the man in Queen Elizabeth I’s court and you win. The nature of the 16th century court can get very confusing and racy to say the least, but Lady Mary Cheke did not stand down to it. Born Mary Hill in 1530s Hampshire England, her father was the wine merchant and master of Henry VIII’s wine cellar. Henry VIII is Elizabeth I’s dad, so there’s a lot going on here. Lady Mary eventually makes her way to the House of Tudor, becoming Elizabeth I’s Lady of the Privy Chamber, or someone who helps the Queen with decision-making, whether political or personal.

We really don’t know much else about Miss Mary Hill, but we do know that she upset a duchess at some point. Through a letter that her husband wrote to the duchess, he had repeatedly told Mary to “be plain” and anticipated that Mary’s “honest nature” would “content” the duchess; it becomes clear that Mary simply spoke her mind. Her husband eventually passed away and she remarried to a gentleman of Elizabeth’s court.

At this point, who started what becomes blurry. The man who “looked after” Mary at the start of our story, Sir John Harrington, writes an offensive poem towards women. Unfortunately, Sir John Harrington had a reputation for this sort of thing. He was booted from England once when he translated an Italian play in a racy way. While he was temporarily banished, he invented the first flushable toilet, wrote a book about it, which also had politically charged commentary. Elizabeth I then banished him for good.

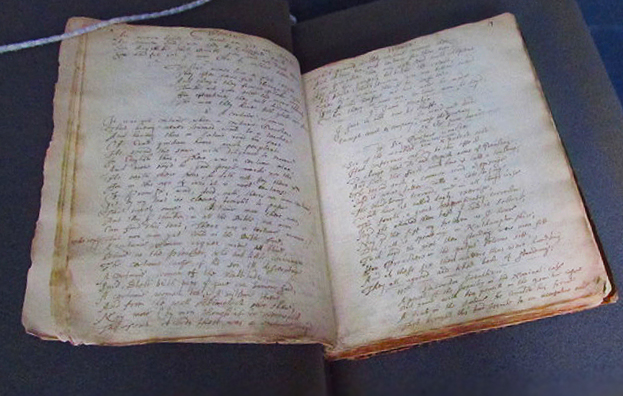

This brings us to the text we have at the Rosenbach: the aggressive epigram written by Sir John Harrington and the counter-epigram written in response by Lady Mary Cheke. An epigram in nature is witty and uses its cleverness to point out a moral, which becomes really clear in the tone we will see. The poems are found back-to-back in Robert Bishop’s commonplace book, which is a book that functions as a scrapbook where the book’s owner would transcribe something they wanted to remember. Bishop’s book in specific has a section of over 80 poems all relating to women. We don’t know anything about Robert Bishop other than that he finished the text in 1630, so he was likely an English citizen just around the time these poets exchanged their poems.

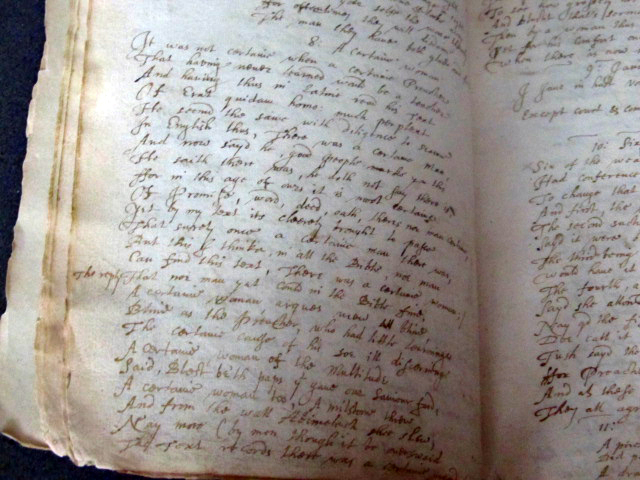

8: A certain woman – Sir John Harrington

1 It was not certain when a certain Preacher

2 That having never learned would be a teacher

3 And having thus in Latin read his text

4 Of Erat quidam homo: much perplex

5 He seemed the same with diligence to scan

6 In English thus, There was a certain man;

7 And now said he, good people mark you this,

8 He said there was, he doth not say there is,

9 For in this age of ours it is most certain

10 Of Promise, word, deed, oath, theres no man certain,

11 Yet by my text is clearly brought to pass

12 That surely once a certain man there was;

13 But this I think, in all the Bible, no man

14 Can find this text, There was a certain woman.

Sir John Harrington’s epigram starts the poem by quoting a preacher giving a sermon who says that the preacher cannot find a “certain” woman in the bible. In other words, he can’t see a woman that does good deeds or oaths and things of that nature. Towards the middle of the page we can see the reply, and this is where Mary comes in with her counter-epigram.

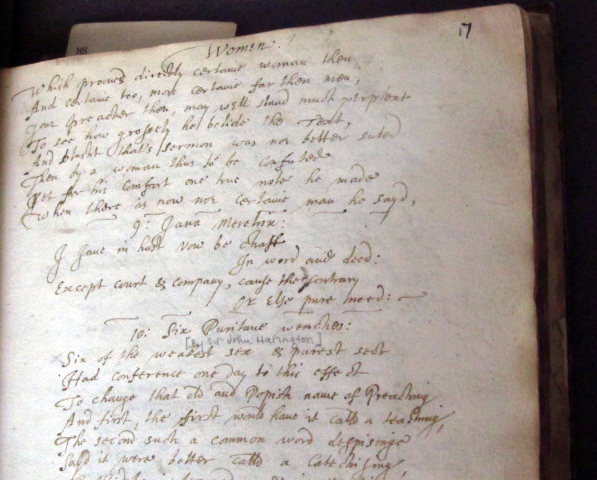

The reply – Lady Mary Cheke (counter-epigram)

1 That no man yet could in the Bible find,

2 A certain woman, argues men all blind,

3 Blind as the preacher, who had little learning

4 The certain cause of his so ill discerning.

5 A certain woman of the multitude

6 Said, Blest be’th paps that gave our Savior food,

7 A certain woman too, A milestone threw

8 And from the wall Abimelech she slew,

9 Nay more, by men though it be oversaid

10 The Text records there was a certain maid.

11 Which proves directly certain woman then

12 And certain too, more certain far then men,

13 Your preacher then, may well stand much perplex

14 To see how grossly he belied the Text,

15 And blusht that’s sermon was no better suited

16 Then by a woman thus to be confuted

17 Yet for his comfort one trust note he made

18 When there is now no certain man he said,

Very witty right?! It’s definitely an epigram in nature. Her response is so lyrically clever, she literally uses Sir John Harrington’s words directly against him by pointing to the preacher, “Blind as the preacher, who had little learning” (3), ouch! Here Cheke doesn’t mean literally “blind”, she is using his ignorance against him showing how “grossly he belied the Text” (14). She even cites the Bible for substantial proof (lines 6 and 7)—she’s ready to send him off with a list of evidence. She also does some really interesting with the lines as well: even though Robert Bishop’s copy of this poem is unfinished, it is still longer than Harrington’s—an example of poetic skill, ending in boastful mastery for the case of women.

To see this poetry showdown in person, along with writings by other female poets such as Phillis Wheatley, Emily Dickinson, and Marianne Moore, register for one of our upcoming Women Poets Hands-On Tours on August 4, August 6, and August 11.

Natalie Risser is the Rosenbach Collections Intern and is a rising senior at Temple University, studying English and minoring in History and Anthropology. She does manuscript readings for Saturnalia Books and was a recipient of the Collegiate Poetry award from the Academy of American Poets this past Spring.