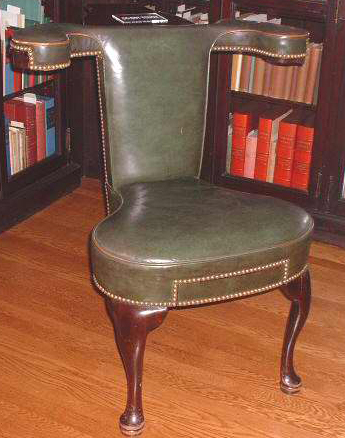

In two weeks, on September 22, our “In Conversation with the Rosenbach” series will feature a conversation on the history of the chair with architectural writer Witold Rybczynski, author of Now I Sit Me Down: From Klismos to Plastic Chair, A Natural History. There are more than 60 chairs in the Rosenbach’s decorative arts collection, but probably the one that generates the most questions on tours is the “cockfighting chair” in the East Library.

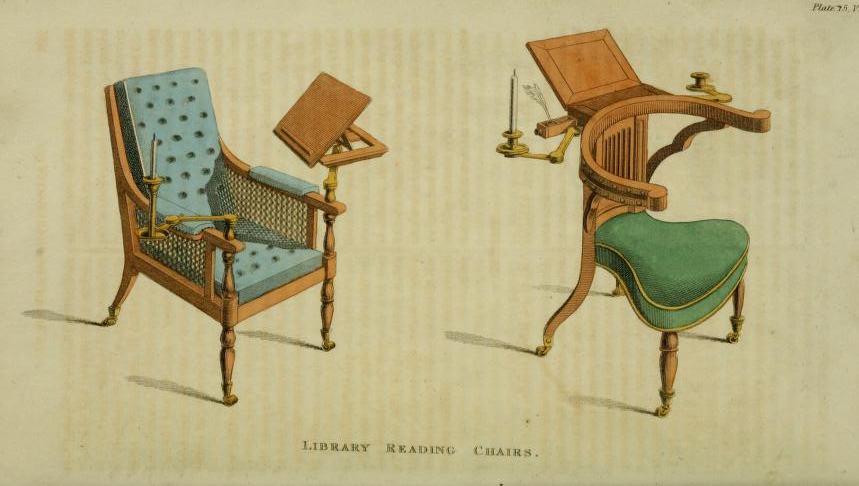

The term “cockfighting chair” seems to be a modern collector’s term; our chair is described this way on the Rosenbach Company’s 1952 purchase invoice from Wood and Hogan. But when chairs like this were created in the 18th and 19th centuries they were described in terms of reading. Here’s an 1810 image of “Library Reading Chairs” from the magazine Ackermann’s Repository.

a more novel article, but equally convenient and pleasant [as the chair on the left]: gentlemen … sit across, with the face towards the desk, contrived for reading, writing, &c. and which, by a rising rack, can be elevated at pleasure… As a proof of their real comfort and convenience, they are now in great sale at the ware-rooms of the inventors, Messrs. Morgan and Saunders, Catherine-street, Strand.

Thomas Sheraton’s furniture design book The Cabinet Directory, published in 1803, also provides an image of this type of chair and a description of its use.

These are intended to make the exercise easy and for the convenience of taking down a note or quotation from any subject. The reader places himself with his back to the front of the chair and rests his arms on the top yoke.

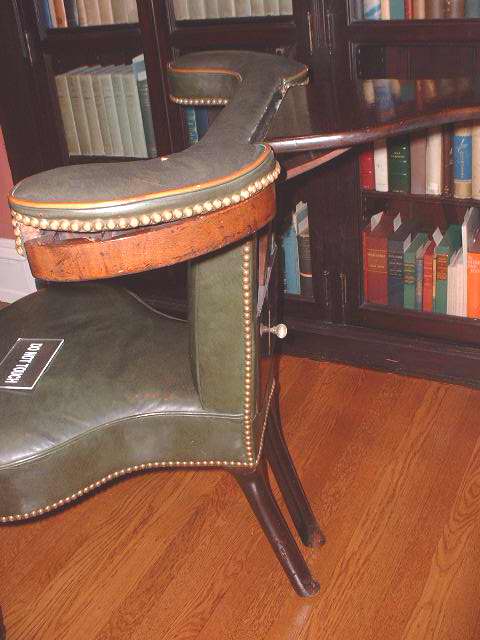

Unlike the examples in Ackermann’s and Sheraton, ours has no convenient candle holders, but it does include drawers under the arms and seat, presumably to hold paper and writing implements for “taking down a note.” Also in contrast to ours, both the Ackermann and Sheraton models have semi-circular arms with the reading surface mounted in a groove so it can be moved along the arms to many different positions. As Ackermann’s explains, “when its occupier is tired of the first position, it is with the greatest ease turned round in a brass grove, to either one side or the other ; in which case, the gentleman sits sideways.”

By the way, I’d like to note in passing that both Sheraton and Ackermann’s describe the user of this furniture in male terms; this would seem to

be a very gendered form of furniture, since women’s clothing would not

have allowed the straddle position the chair was designed for, nor would

it have been considered seemly, although maybe the sideways position described by Ackermann might have been acceptable.

Another drawing of a reading chair with arms more similar to ours turns up in the Winterthur library, which preserves drawings of furniture made ca. 1780-1810 by the Gillow Company. This chair is described in the company’s estimate book (apparently in the Westminster archive) as “a mahogany reading chair”

In addition to these images, examples of reading chairs like ours survive in a number of collections. Here’s a ca. 1750 example from the Met.

And here’s a 1725-35 example from London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

This ca. 1720 example, also from the V&A is thought to have belonged to John Gay, who wrote the Beggar’s Opera.

Preservation concerns keep me from trying out our cockfighting chair to personally assess its ergonomic and comfort qualities, but the form seems to have had a long run and is certainly an ingenious and fascinating piece of furniture.