Between the crazy drama of this election season and the crazy popularity of the musical Hamilton, it seems an apropos time to look at some on-the-spot reporting from the crazy election of 1800. For those of you who have seen or listened to Hamilton, or just remember your history books, you’ll recall that the election of 1800 came out as tie in the electoral college between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr.

Pinckney against Jefferson and Burr from the Democratic-Republican party (generally called “the Republican party” by historians). Constitutional election rules had not foreseen the rise of political parties and did not separate presidential and vice presidential voting; instead, each member of the electoral college voted for two men with the overall winner becoming president and the runner up becoming vice president. When the electoral college met, one Federalist elector cast a throwaway vote for John Jay rather than Pinckney, giving Adams 65 and Pinckney 64. However, despite the fact that the Republican party had seen Jefferson as the Presidential nominee and Burr as V.P., all of the Republican electors voted for both Jefferson and Burr, leading them to tie at 73 votes apiece .

With the electoral vote tied, the choice between Jefferson and Burr was to be decided by the House of Representatives. In the run-up to the House vote Alexander Hamilton tried to convince his fellow Federalists to back Jefferson, who “though too revolutionary in his notions, is yet a lover of liberty and will be desirous of something like orderly Government – Mr. Burr loves nothing but himself – thinks of nothing but his own aggrandizement – and will be content with nothing short of permanent power in his own hands.” Hamilton, an experienced political deal-maker, argued that Federalists would not be able to trust the self-interested Burr, since “no compact, that he should make with any passion in his breast except Ambition, could be relied upon by himself – How then should we be able to rely upon any agreement with him?” Hamilton thought Jefferson might be willing to accept a bargain that including retaining the Federalist monetary system, the navy, and low-level Federalist office holders in exchange for Federalist support in the House vote. But Jefferson declined.

Voting finally began in the House of Representatives on Wednesday February 11, 1801. Each state delegation would get one vote; since there were sixteen states at the time (the original thirteen plus Vermont, Kentucky and Tennessee) nine votes were need to win. The Republicans controlled eight

congressional delegations and the Federalists, who backed Burr despite Hamilton’s efforts, controlled six, with two states deadlocked. As the day wore on, in ballot after ballot neither Jefferson nor Burr could reach nine votes.

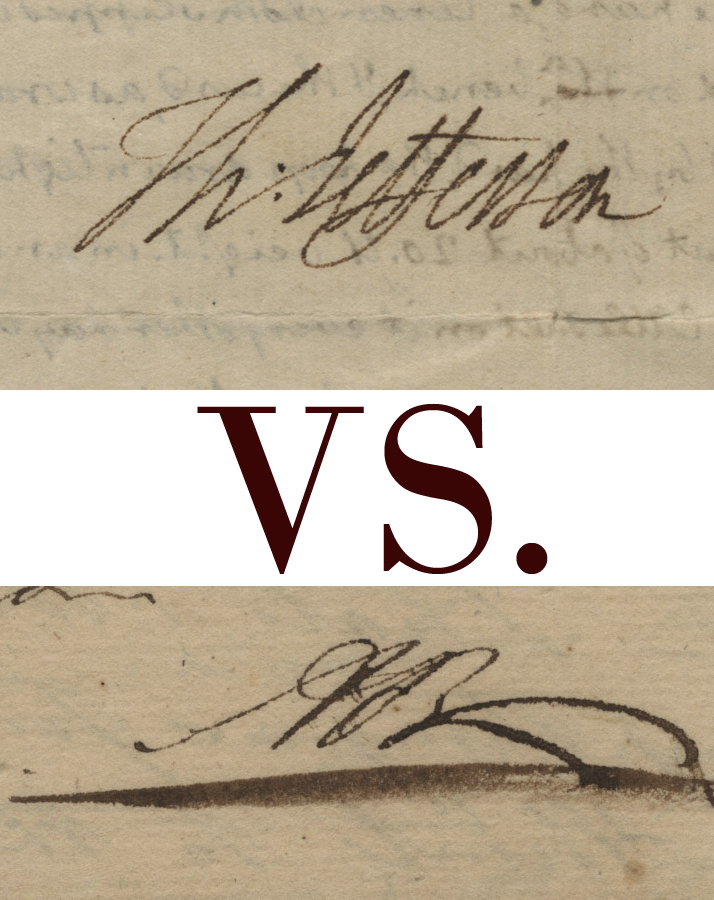

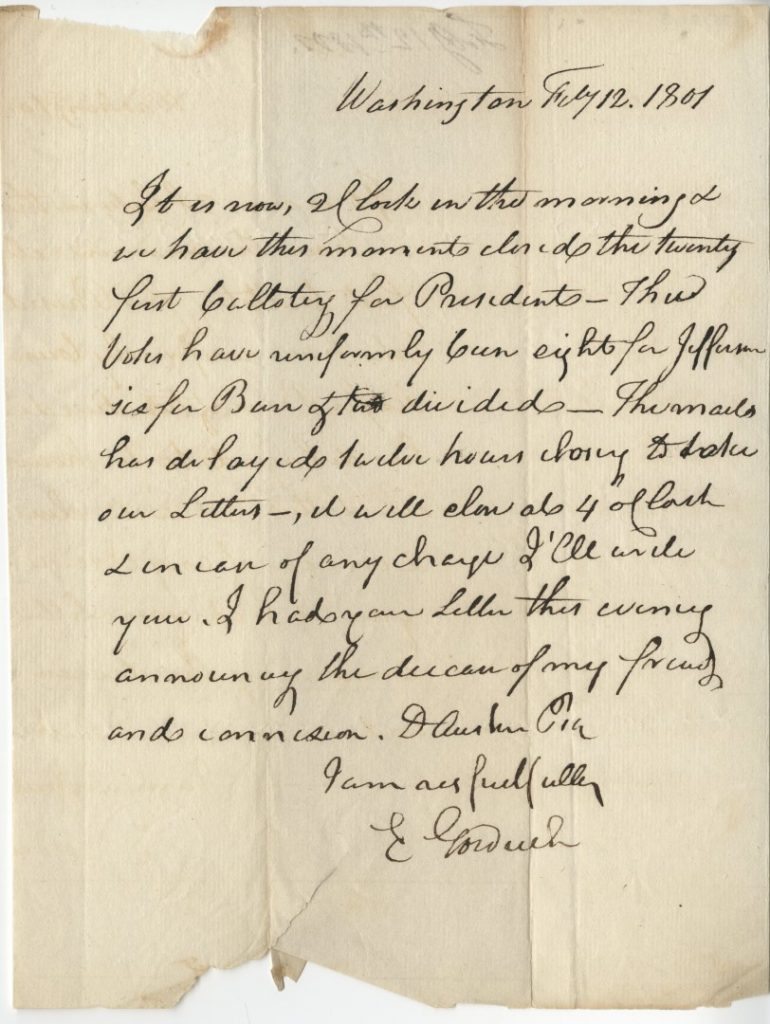

A letter in our collection was written from Connecticut Representative Elizur Goodrich to a New Haven lawyer “at two clock in the morning & we have just this moment closed the twenty first balloting for president. The votes have uniformly been eight for Jefferson, six for Burr, & two divided.”

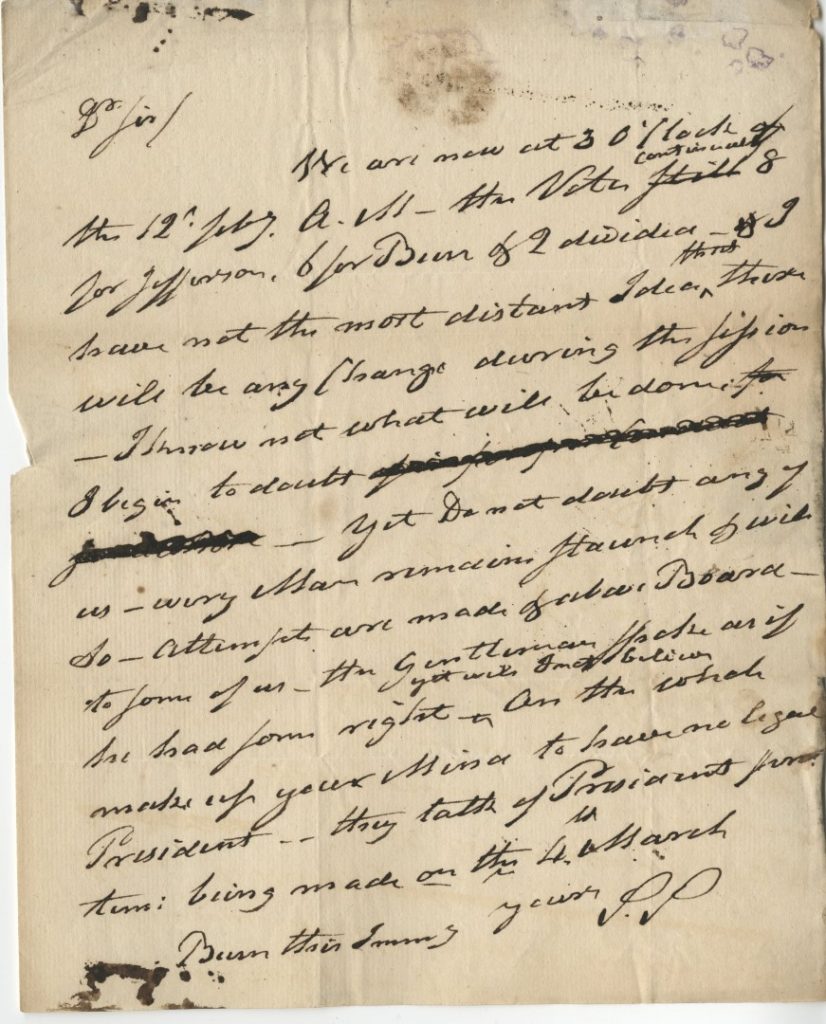

Congress remained in session and an hour after Goodrich’s dispatch, representative Samuel Smith from the deadlocked state of Maryland wrote a letter to Republican-party organizer Alexander Dallas indicating, “We are now at 3 o’clock of the 12th February A.M. The votes continually 8 for Jefferson, 8 for Burr, & 2 divided. I have not the most distant idea that there will be any change this session.”

Smith’s letter mentions that “attempts are made…to some of us” to convince members of his deadlocked delegation, but concludes, “On the whole make up your mind to have no legal president–they talk of President pro tem being made on the 4th March.” The specter of having of having no President in place by election day was alarming and as the days went on with increasing numbers of House votes leading to no decision, the situation grew increasingly tense. As historian Gordon Wood explained, “Republican newspapers talked of military intervention. The governors of Virginia and Pennsylvania began preparing their state militias for action. Mobs gathered in the capital and threatened to prevent any president from being appointed by statute.”

Samuel Smith would actually play an important role in breaking the deadlock. On Monday February 16, Smith relayed assurances to the lone Delaware representative, James Bayard, that Jefferson would be willing to accept the Federalist’s deal. Burr apparently was not; Bayard later wrote to Hamilton that “Burr was resolved not to commit himself.” On Tuesday, February 17, Bayard and the Federalists in three other states abstained and Jefferson was finally elected on the 36th ballot by a margin of 10-4 with two abstentions.

In the aftermath, Jefferson himself disavowed that he had many any deals, leaving historians to fight over exactly what was or wasn’t said. Congress was also determined to to repeat this particular fiasco, so it passed the 12th amendment in 1803 (ratified in 1804) to separate the electoral college’s balloting for President and Vice President.

Had enough yet? This was only a small sliver of the crazy election of 1800. We didn’t get into the partisan nastiness or any of the electioneering. But if you’re feeling overwhelmed, I’ll leave you with the much more succinct version from Hamilton.