|

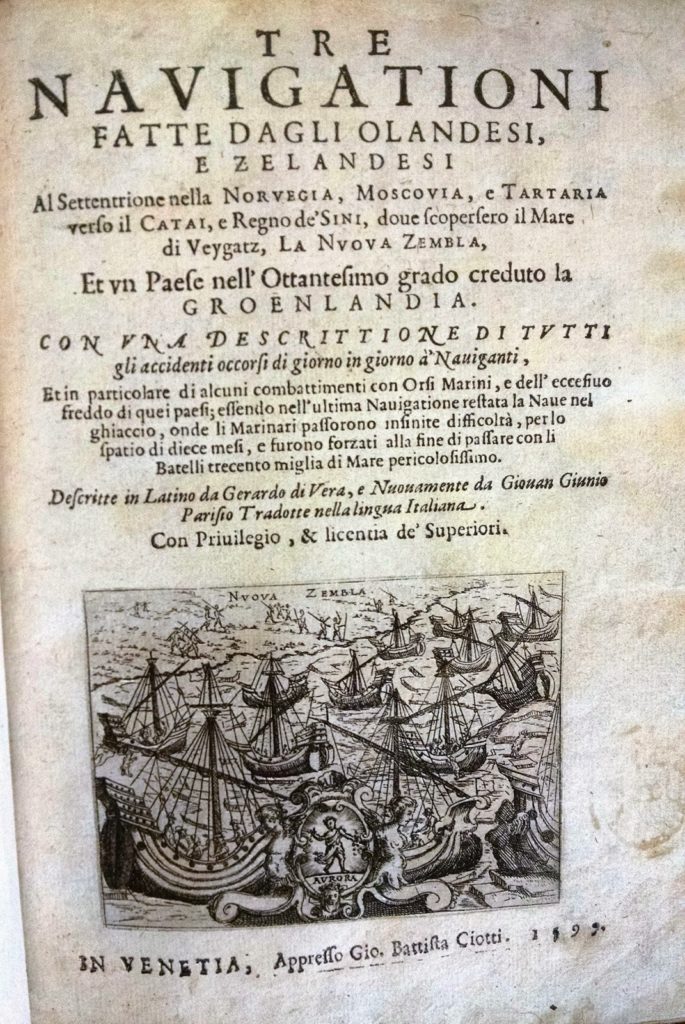

| The first Italian edition of Gerrit de Veer’s diary of his arctic voyages (Tre Navigationi Fatte Dagli Olandesi e Zelandesi… Venice: Printed by Giovanni Battista Ciotti, 1599. A 599t). |

With a -2 degree windchill today seems like an appropriate

day to consider a book about the arctic. You may have heard of the

Northwest Passage, the theoretical sea-route across arctic Canada and

Alaska that many explorers sought over the centuries (and the remains of

one of their ships has been in the news fairly

recently). Well, there’s also a Northeast Passage across northern

Siberia by which you could travel from the Atlantic to the Pacific,

though it’s not for the faint of heart. The Dutch navigator Willem Barentsz attempted to find the passage on three voyages from 1594-7, and he died at sea during the last of these. Fortunately, an officer on two of these expeditions, Gerrit de Veer, kept a journal (no doubt with frostbitten fingers), which was published upon his return to Amsterdam. Ours is an Italian version from 1599 but an English edition was published in 1609.

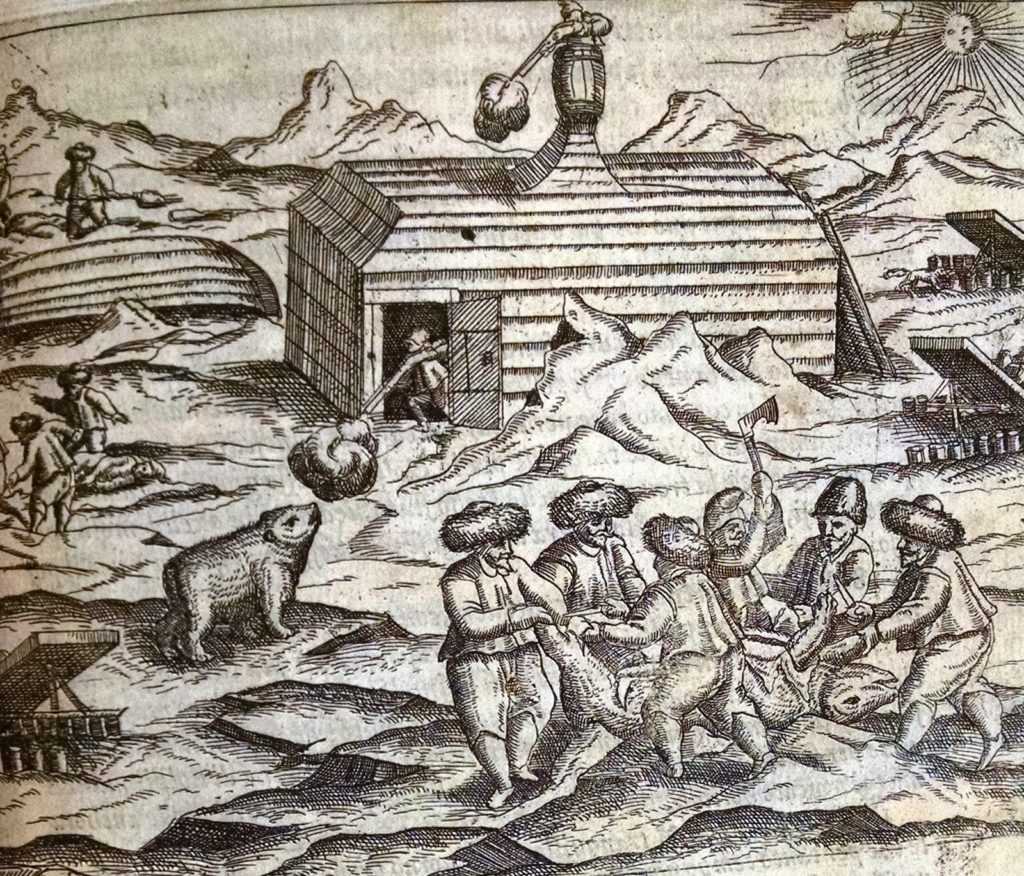

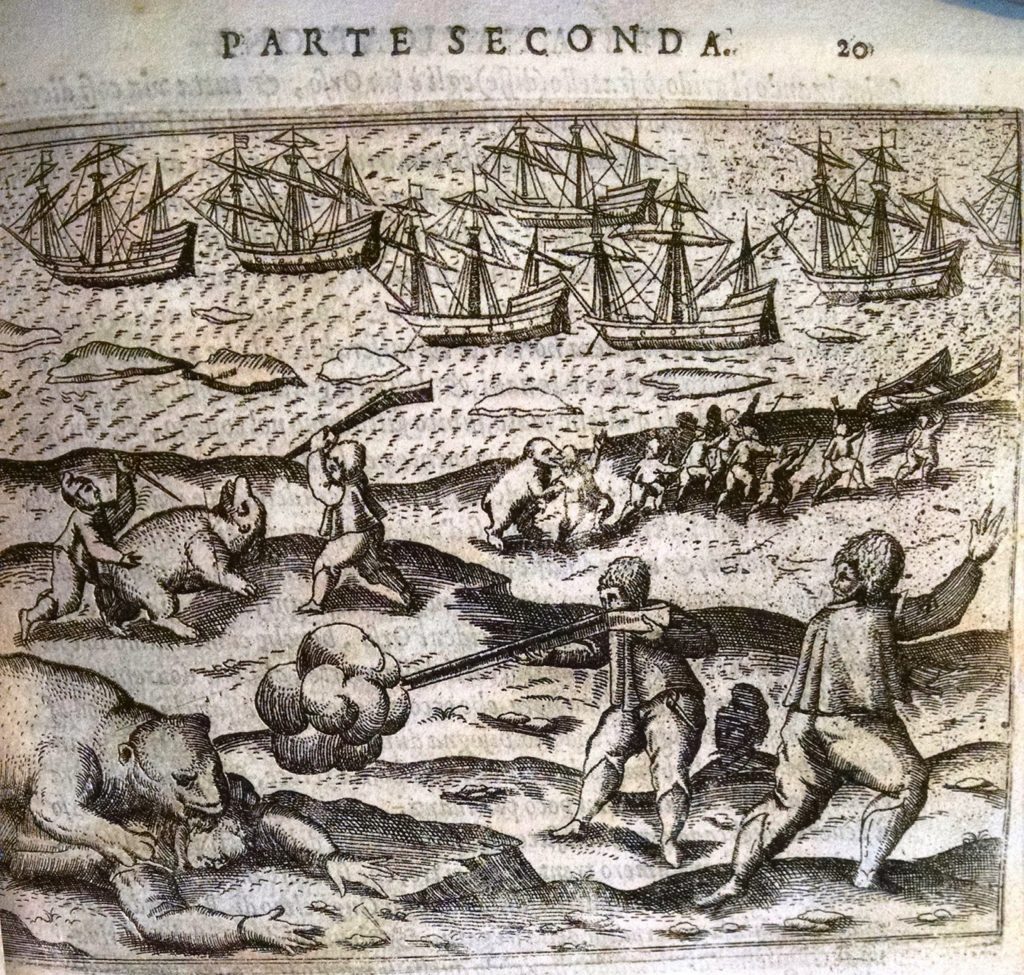

Barentsz’s mission wasn’t the first–and wouldn’t be the last–arctic expedition to suffer major setbacks. Sea ice was a constant threat, even in the summer, and polar bears could be dangerous. De Veer chronicled several run-ins with the large predators, none of which ended well for the bears. During the group’s third voyage in 1597, their ship reached the large island of Novaya Zemlya (“Nova Zembla” as they called it) but became trapped by ice. Using wood from the ship, the crew constructed a lodge and used it to survive on the frozen tundra for 10 months before finally being able to take to the sea again. After using up whatever provisions were on board the ship they took to trapping arctic foxes for food. At one point, having shot a polar bear with their muskets, they used its blubber to light their lamps, and at another point they ate a bear’s liver. Since the liver of arctic mammals is exceedingly high in vitamin A, and polar bears eat lots of seals, de Veer ended up recording the first written instance of hypervitaminosis A: he and his crew experienced headaches and nausea, bone pain, and eventually widespread peeling of their skin. The symptoms didn’t linger too long but were a complication the stranded and freezing Dutchmen could have done without.

Barentsz’s mission wasn’t the first–and wouldn’t be the last–arctic expedition to suffer major setbacks. Sea ice was a constant threat, even in the summer, and polar bears could be dangerous. De Veer chronicled several run-ins with the large predators, none of which ended well for the bears. During the group’s third voyage in 1597, their ship reached the large island of Novaya Zemlya (“Nova Zembla” as they called it) but became trapped by ice. Using wood from the ship, the crew constructed a lodge and used it to survive on the frozen tundra for 10 months before finally being able to take to the sea again. After using up whatever provisions were on board the ship they took to trapping arctic foxes for food. At one point, having shot a polar bear with their muskets, they used its blubber to light their lamps, and at another point they ate a bear’s liver. Since the liver of arctic mammals is exceedingly high in vitamin A, and polar bears eat lots of seals, de Veer ended up recording the first written instance of hypervitaminosis A: he and his crew experienced headaches and nausea, bone pain, and eventually widespread peeling of their skin. The symptoms didn’t linger too long but were a complication the stranded and freezing Dutchmen could have done without.

The dangers of ice, hypothermia, and bears aside, de Veer did record observations on some wondrous people and phenomena encountered in the arctic. On Barentsz’s second voyage they met groups of Nenets, one of the indigenous peoples of Northern Russia (called “Samiuti” here, derived from the now outdated term “Samoyeds”), with whom they had good relations. De Veer described their reindeer fur clothing and weapons in detail and the Dutchmen shared some of their ship’s biscuit with the Nenets chief.

De Veer also recorded an atmospheric phenomenon now known as the Novaya Zemlya effect, a kind of mirage in which a sun that is actually below the horizon and shouldn’t be visible has its rays reflected like a mirror by a thermal inversion (warm air on top of cold air). What de Veer observed was a weirdly distorted sun, flattened out like a pancake and repeated, which the engraver of the volume in our collection rendered in this fanciful image of a dual-sun with a suggestion of rays emanating from the sides. How’s that for finding a silver lining on a frigid day?

Patrick Rodgers is a curator at the Rosenbach Museum & Library.

Patrick Rodgers is a curator at the Rosenbach Museum & Library.