This blog post was written by Andrew White

Folk horror! I think of old chestnuts like The Wicker Man, or new Ari Aster movies like Midsommar and Hereditary. But before folk horror was a genre of cinema it was a literary genre: folk horror thrives on Rosenbach library shelves in early Shakespeare printings of Macbeth and The Winter’s Tale, first editions of Christina Rossetti’s spellbinding Goblin Market, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Thrawn Janet (terrifying!) and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s textbook folk horror Young Goodman Brown. We also possess the manuscript of Robert Burns’s folk horror ballad, Tam O’Shanter. This Halloween my goal is to sketch a folk horror plot for you the Rosenbach way, with objects from our collection. I’ll limit myself to the art of illustration—one of The Rosenbach’s preeminent strengths—and specifically the illustrations of 19th century caricaturist and illustrator George Cruikshank.

Folk horror! I think of old chestnuts like The Wicker Man, or new Ari Aster movies like Midsommar and Hereditary. But before folk horror was a genre of cinema it was a literary genre: folk horror thrives on Rosenbach library shelves in early Shakespeare printings of Macbeth and The Winter’s Tale, first editions of Christina Rossetti’s spellbinding Goblin Market, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Thrawn Janet (terrifying!) and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s textbook folk horror Young Goodman Brown. We also possess the manuscript of Robert Burns’s folk horror ballad, Tam O’Shanter. This Halloween my goal is to sketch a folk horror plot for you the Rosenbach way, with objects from our collection. I’ll limit myself to the art of illustration—one of The Rosenbach’s preeminent strengths—and specifically the illustrations of 19th century caricaturist and illustrator George Cruikshank.

Hey Andrew, what is this “folk horror” you speak of anyway? According to Adam Scovell’s British Film Institute article, “Where to Begin With Folk Horror,” three English films exemplify folk horror in cinema—where we encounter it most. Scovell cites The Witchfinder General, The Blood on Satan’s Claw and The Wicker Man as the genre’s “unholy trinity.” (For me only the latter is watchable, but prepare to endure the awkward musical interludes if you want to see Christopher Lee giving the performance of his career). The U.S. has a thriving cinematic folk horror tradition too, as exemplified by an alternate “unholy trinity” comprised of Ari Aster’s aforementioned movies, The Children of the Corn, and the Candyman films. But whether here or there, the archetypal folk horror tale will feature an outsider entering a rural community and discovering a living pagan culture with a bloodthirsty, and maybe supernatural animus as its guiding spirit, and fighting for survival before becoming the community’s next human sacrifice.

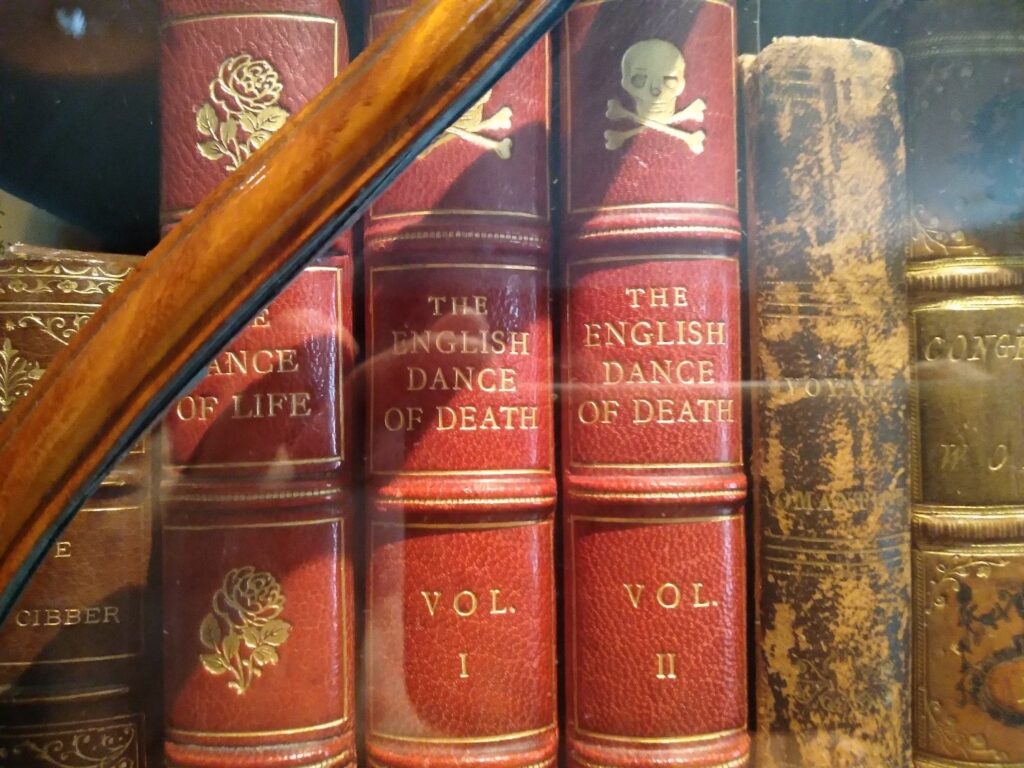

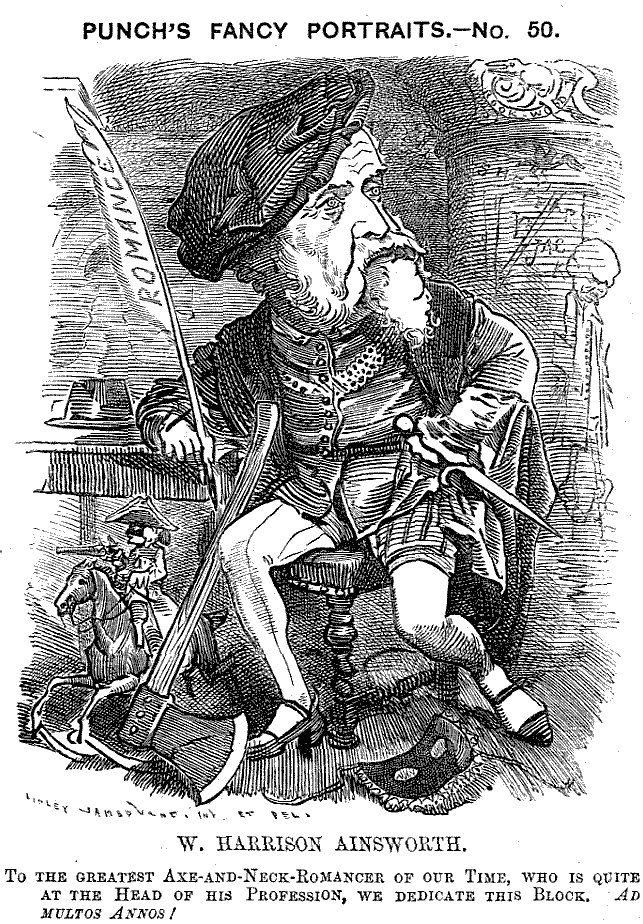

For our Rosenbach folk horror tour let’s properly introduce our (unwitting) host, the celebrated British illustrator and satirist George Cruikshank. As the son of illustrator and caricaturist Isaac Cruikshank, George was born, as they say, in the business. His lengthy career stretched from the Regency era into the later reign of Victoria. In 1820, his gift for sending up the lofty won him a royal bribe in exchange for a promise “not to caricature his Majesty [then George III] in any immoral situation.” For the second quarter of the 19th century Cruikshank became Britain’s most popular and influential children’s book illustrator. John Ruskin, the supreme, king-making art critic, compared Cruikshank’s work to Rembrandt’s—a bit of a stretch maybe, but that gives you a sense of Cruikshank’s preeminence in his field. Cruikshank is remembered chiefly for early political cartoons and later illustrations–particularly those he did for Dickens. The Rosenbach has a remarkable four thousand Cruikshank prints and illustrations, which can be scrolled through here in the Rosenbach’s “Phil” database.

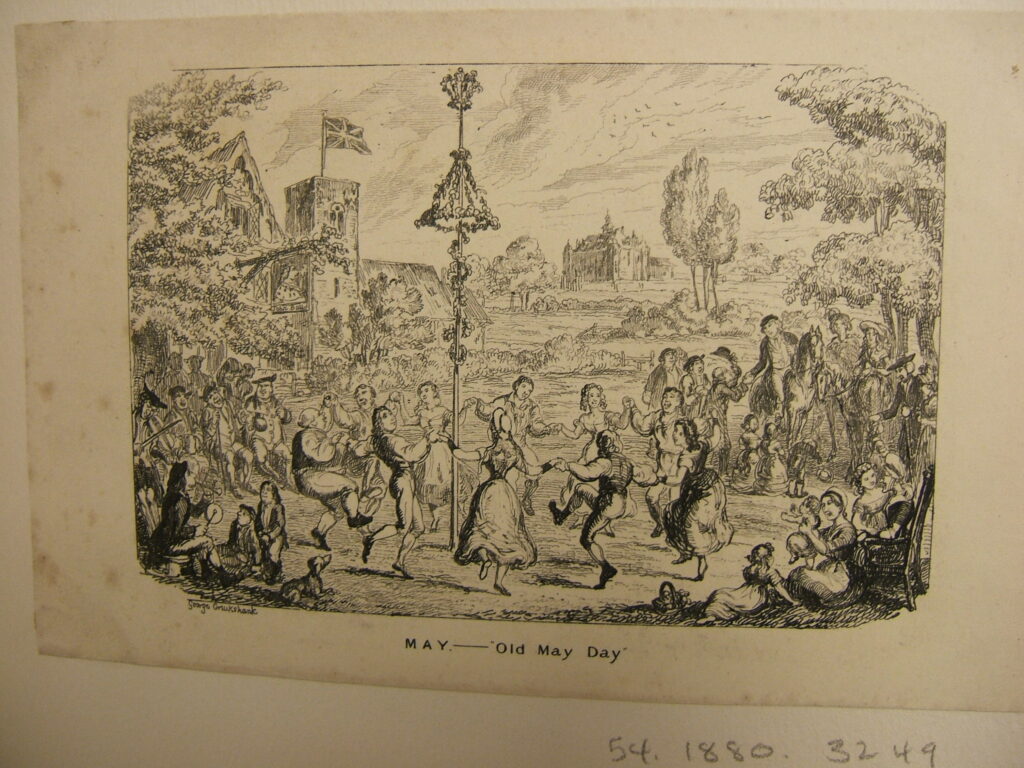

Cruikshank sets the stage for the first act of our folk horror road show with an etching, “Old May Day, which originally illustrated “The Comic Almanack for 1836.” It gives us young village swells and maidens enjoying the seasonal pastime of dancing around a maypole–which I’m sure you’ll agree is entirely harmless:

Or is it? Distrusting their pagan origins, Puritans outlawed maypoles when they joylessly ruled England in the third quarter of the 17th century. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “The Maypole of Merry Mount ” imagines a moment in U.S. history—or pre-history—when the Puritan governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony orders a maypole cut down and the people of the community—Merry Mount—who erected it, whipped.

Or is it? Distrusting their pagan origins, Puritans outlawed maypoles when they joylessly ruled England in the third quarter of the 17th century. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “The Maypole of Merry Mount ” imagines a moment in U.S. history—or pre-history—when the Puritan governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony orders a maypole cut down and the people of the community—Merry Mount—who erected it, whipped.

On that fittingly gloomy note, on to Act II: From deceptively innocent scenes of pastoral idylls a Folk Horror story will introduce an element of rustic foreboding: these simple peasants are somehow sinister; you smell violence on the wind. I may be overdoing it with the hand-colored Cruikshank etching below, which shows farmers and working men carting a lawyer, doctor, and vicar out of town, but it fits the vibe as our plot begins its inevitable thickening..:

And: it’s fun to see Cruikshank at his most acerbic. This image arises from a time of popular unrest in England; the proverbial flashpoint for which was the Peterloo Massacre. In the summer of the year this etching was produced, 1819, a peaceful rally of working men and women was organized by the Manchester Patriotic Union to advocate for parliamentary reform. The demonstration was scheduled for a clearing by the Manchester Friends Meeting House, called St. Peter’s Field. The Manchester Yeomanry, which was formed in response to unrest in northern England two years before, was deployed to break up the meeting. The Yeomanry charged into the field; eleven demonstrators were killed, and many more were injured. So from a blog post about imaginary horrors, a real historical horror emerges—one that echoes eerily with events of the present day.

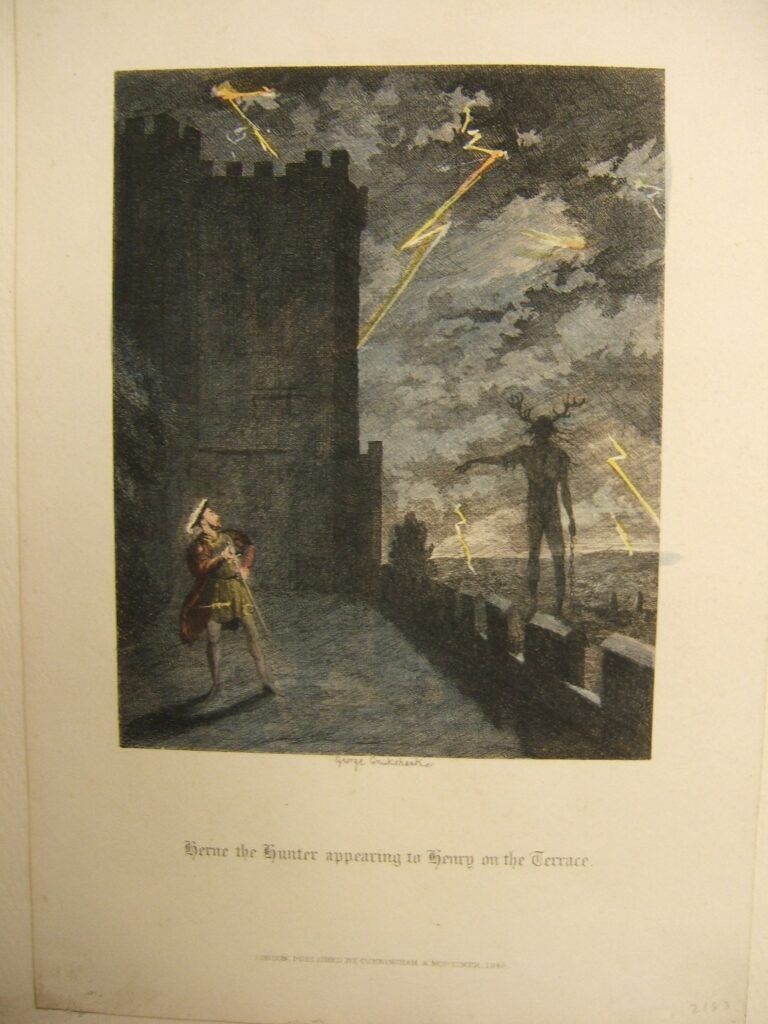

Moving on, for the third act of our folk horror show let’s complicate matters by introducing a supernatural element: Folk horror doesn’t always have one, but my Gothic heart loves a good ghost or vengeful nature spirit. Here I’ll invoke Herne the Hunter, also called Cernunnos, the antlered elemental who has haunted Britain since Celtic days:

As illustrated by George Cruikshank, Herne here menaces Henry VIII in a scene from the 1842 novel Windsor Castle. Ignoring the tarnished Tudor’s histrionic pose, I can savor the angular lightning, smoky sky, moonlit crenellation, and Herne’s elegant silhouette in this hand-colored etching. The main plot of Windsor Castle has Henry swapping Catherine of Aragon for Anne Boleyn, and we all know how that turns out. Herne is relegated to a subplot, but avenges this affront by stealing every scene he’s in:

Turning at the sound, Henry perceived a tall dark figure of hideous physiognomy and strange attire, helmed with a huge pair of antlers, standing between him and the oak-tree. So sudden was the appearance of the figure, that in spite of himself the king started.

“What art thou—?” he demanded.

“I am Herne the Hunter,” replied the demon. “Welcome to my domain, Harry of England. You are lord of the castle, but I am lord of the forest. Ha! ha!”

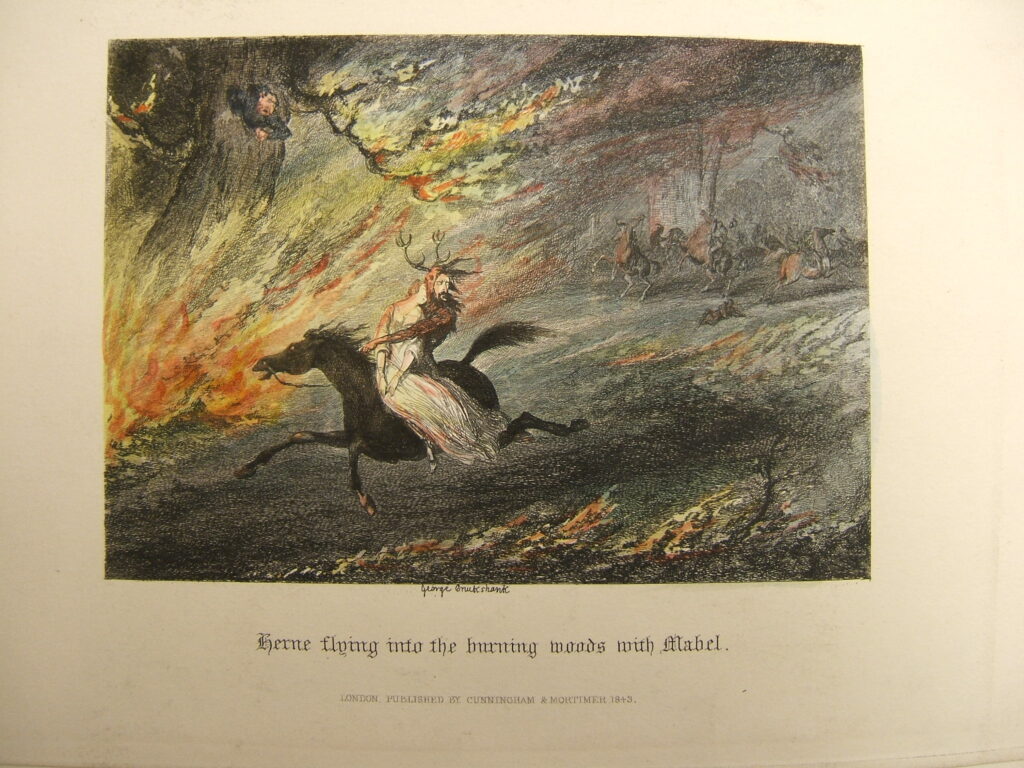

The author of Windsor Castle, William Harrison Ainsworth, had an interesting connection to the Peterloo Massacre. He was a child in Manchester when it happened, and two of his uncles were among the protesters. A productive historical novelist and friend of Charles Dickens, it was Ainsworth who introduced Dickens to Cruikshank—sparking a mutually-beneficial partnership that led to their collaboration on the first printings of Sketches by Boz, Oliver Twist, Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend. Prolific and popular—in life—Ainsworth wrote more novels than Sir Walter Scott, though fewer than Joyce Carol Oates, and after death joined the ranks of historical figures no one claims to be the reincarnation of. Only Ainsworth’s Windsor Castle and Lancashire Witches were in print a century after their publication. For the fourth and penultimate act of our Choose-Your-Own-Folk-Horror, now that we’ve established the rustic setting, charming/threatening locals, and introduced at least a murmur of the supernatural, it’s time for some mishaps and grisly accidents to befall our dramatis personae, don’t you agree? In Windsor Castle, “Mabel” is the virtuous daughter of Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor and chief adviser. Mabel gets carried off by Herne, and later expires, which could explain why no “Mabel Wolsey” exists in the historical record. Below, see Mabel fainting against her supernatural captor in a satisfyingly ladylike fashion while the good guys’ attempt to pursue is thwarted by a convenient forest fire:

For the fourth and penultimate act of our Choose-Your-Own-Folk-Horror, now that we’ve established the rustic setting, charming/threatening locals, and introduced at least a murmur of the supernatural, it’s time for some mishaps and grisly accidents to befall our dramatis personae, don’t you agree? In Windsor Castle, “Mabel” is the virtuous daughter of Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor and chief adviser. Mabel gets carried off by Herne, and later expires, which could explain why no “Mabel Wolsey” exists in the historical record. Below, see Mabel fainting against her supernatural captor in a satisfyingly ladylike fashion while the good guys’ attempt to pursue is thwarted by a convenient forest fire:

By the end of Windsor Castle Cardinal Wolsey has been executed, Mabel drowned, Catherine of Aragon discarded, Anne Boleyn beheaded, and only Henry and Herne are left standing.

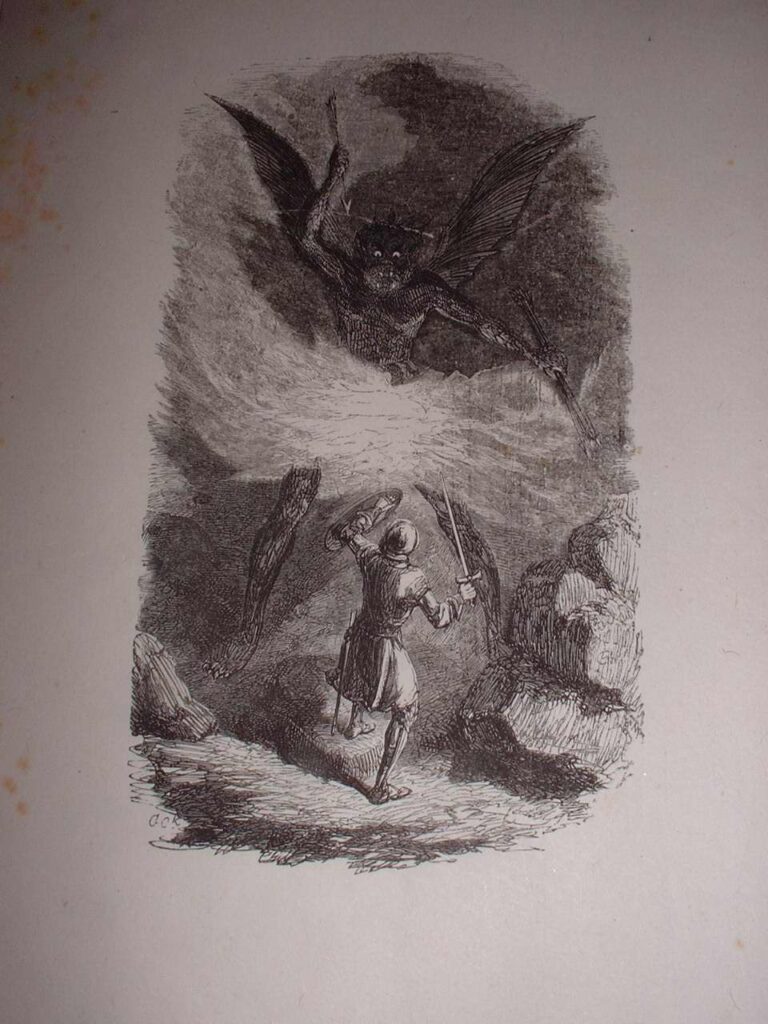

For the climax of our imaginary Rosenbach folk horror the obvious choice would be William Blake’s impressively infernal The Number of the Beast is 666, the glory of our third floor, a work Blake did as part of a series on the Book of Revelation, and an image that was later used as an album cover for the Finnish metal band Chalice. But rather than go with the obvious I’ll stay with Cruikshank for our story’s resolution. The engraving below was done for John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and shows our hero Christian confronting the demon Apollyon, who comes armed with threats, flattery, and flaming darts, and who takes half a day to be finally dispatched. Cruikshank’s Apollyon looks like a sooty version of the Abominable Snowmonster or “Bumble” in the Rankin/Bass stop-motion Rudolph. He’s also is a dead ringer for the unnamed fiend whose long-dreaded appearance crowns Jacques Tourneur’s not-bad 1957 folk horror Night of the Demon—which is why he’s included here:  “Apollyon” or the “Destroyer,” is the Greek version of the Hebrew “Abaddon.” The Book of Revelation describes Apollyon as commanding an army of terrifying mutant locusts with long hair, lions’ teeth, iron breast-plates, and scorpion stingers. Christians have regarded Apollyon as the Anti-Christ or Satan himself, but specific sects, such as the Methodists and Jehovah’s Witnesses, have rehabilitated Apollyon as a mere henchman of God who’s a little rough around the edges. Not all folk horror movies summon real demons at their climax, but a parallel to big boss Apollyon here is Paimon, the demonic duke and lapdog of Lucifer who dominates the unlucky Graham family in Hereditary.

“Apollyon” or the “Destroyer,” is the Greek version of the Hebrew “Abaddon.” The Book of Revelation describes Apollyon as commanding an army of terrifying mutant locusts with long hair, lions’ teeth, iron breast-plates, and scorpion stingers. Christians have regarded Apollyon as the Anti-Christ or Satan himself, but specific sects, such as the Methodists and Jehovah’s Witnesses, have rehabilitated Apollyon as a mere henchman of God who’s a little rough around the edges. Not all folk horror movies summon real demons at their climax, but a parallel to big boss Apollyon here is Paimon, the demonic duke and lapdog of Lucifer who dominates the unlucky Graham family in Hereditary.

Cruikshank shies away from showing the full monstrosity of Bunyan’s Apollyon, who is described as having scales like a fish, wings like a dragon, feet like a bear, a mouth like a lion, and fire and smoke pouring out of a hole in his middle, but Cruikshank may have accepted a bribe from Satan to soften the appearance of some of his demons.

So that’s it for your Rosen-primer on folk horror, a genre that is dear to my heart even if most of the movies are rubbish. One exception, and I’ll leave you with this recommendation, is the 1965 Japanese anthology movie Kwaidan, poetic and petrifying and hearty enough to while away a blustery Halloween night as you hide from trick-or-treaters. Alternately, celebrate All-Hallows Eve the Rosenbach way with an autumnal libation and communal read-aloud of Young Goodman Brown, Thrawn Janet, and Goblin Market, and taste real folk horror straight from the source! The shadows in your house will seem longer, the night’s silences more sinister, and the wind will wuther more woefully… but don’t get too frightened —enjoy! And Happy Halloween from The Rosenbach!