I was in graduate school when Oprah Winfrey confronted author James Frey about fabricating portions of his memoir, A Million Little Pieces. Oprah, who had previously defended Frey’s memoir as a meaningful book with or without a strict adherence to the facts, apologized to her viewers: “I left the impression that the truth does not matter, and I am deeply sorry about that.” (USAToday).

Being graduate students, my cohort and I couldn’t help overthinking this. How true do we want true stories to be? Does a story have more impact if it’s completely, entirely true? Aren’t all stories, even true ones, a little bit fictionalized when we arrange them neatly into a compelling narrative? And if the competing demands of true memoirs and sensational stories create a situation like Frey’s, who is accountable for it—the author, the publisher, or the reading public?

These aren’t merely the existential questions of postmodern writers today; they might also apply to a novel that is considered one of the important texts of the English language canon.

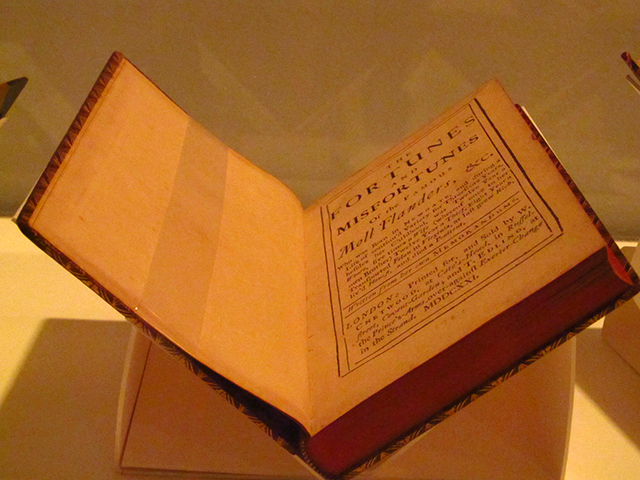

At first glance, Moll Flanders appears to be a criminal biography–a genre of book that narrates a criminal’s life from birth to first contact with crime to death or penitence, whichever came first. This type of publication rose in popularity in 18th century England and purported to offer moral instruction, although these tales of criminal escapades and temptations can sometimes be more titillating than instructive. The story of Moll Flanders is set in the 17th century and spans two continents along with (as the lengthy subtitle explains) 12 years of prostitution and 5 marriages, the latter of which were mostly arranged under false pretenses. Moll’s life of crime is influenced by the unfortunate circumstances of her life–for example, having been raised without knowing her parents, she doesn’t recognize her mother until after she unwittingly marries her own half-brother–but her narrative, written in the first person perspective, depicts a woman who chooses crime as a means to relative luxury and comfort. Her story makes for scandalous reading, though the illusion that she is telling the story herself may also appeal to the reader’s sympathy.

Moll Flanders was published anonymously with a preface explaining that a real-life Moll had recounted her life story to an author, who greatly edited her account “to make it speak language fit to be read,” and assures the reader that he has left the most vicious parts of her story out. What remains, the preface author insists, is necessary to give full meaning to Moll’s eventual redemption: “To give the history of a wicked life repented of, necessarily requires that the wicked part should be make as wicked as the real history of it will bear, to illustrate and give a beauty to the penitent part, which is certainly the best and brightest, if related with equal spirit and life.” (The reader may find it debatable whether Moll’s penitence is related with equal spirit and life, as it is neatly encapsulated in the final sentence of the book.)

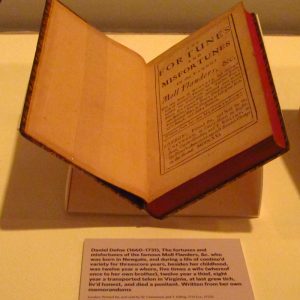

Moll Flanders was not attributed to the famous 18th-century author Daniel Defoe until nearly fifty years after the book was published and several decades after Defoe’s death, so we can know little about his intent or inspiration for this book. Was Moll Flanders real? While sensational, Moll’s transatlantic escapades are no more improbable than those of Betty Robinson, colonial cat burglar. On one hand, we know that Defoe was acquainted with a woman named Moll King who was imprisoned in Newgate and often thought to be the inspiration for Moll Flanders; on the other hand, Defoe’s story bears only a passing resemblance to a later criminal biography, The Life and Character of Moll King (published anonymously in 1747). On one hand, Defoe was a prolific pamphleteer who had spent time in Newgate himself for political dissent; his primary mode of writing was nonfiction. On the other hand, Defoe had previously authored what some consider the first English novel, Robinson Crusoe, and as the preface explains, he took pains to craft a compelling narrative out of Moll’s erratic story. So it remains a mystery whether Moll Flanders is a true criminal biography or an early novel.

But the question reminds me of the questions raised by A Million Little Pieces and other contemporary instances of authors publishing fabricated or exaggerated tales of crime, danger, or addiction. Given the trials and tribulations of her life, do we necessarily want Moll Flanders to be real? If fabricated, was her story intended to elicit sympathy or revulsion or perhaps a little bit of both? In either case, how true can a well-crafted narrative ever be–and what do we as readers expect to get out of reading true stories that we wouldn’t get from reading fiction? Has that changed in nearly three centuries since Moll Flanders was published?

You can ponder these mysteries, among others, in the exhibition Clever Criminals and Daring Detectives, where Moll Flanders and other genre-defying books will be on view through September 1.