This blog post was written by Andrew White

What would you say to a look at some tender and romantic love letters from Marlene Dietrich, the 20th century German American actress and singer whose life and art continue to inspire? It’s the 7th week of social distancing—counting from the Ides of March when the Rosenbach went exclusively digital—and we all could use a lift. Cue Dietrich. Marlene Dietrich had a Bowie-like ability to reinvent herself over her 70 year career, was openly bisexual in the 1930s (at least in Hollywood circles), and was a maestro of friendship—her longstanding bonds with Ernest Hemingway, Orson Welles, and Jean Cocteau provide an index of her depth—and theirs.

I should also mention that the wry androgynous sphinx Dietrich projected on film is one of the great creations of Western art. If that weren’t enough for one lifetime, the finest thing about Dietrich is her deeply lived anti-fascism. In the 1930s, immediately after emigrating from Germany herself, Dietrich worked with movie directors Ernst Lubitsch and Billy Wilder to fund escapees from Hitler’s Germany and help them emigrate to the States. When World War II started Dietrich was one of the first celebrities to sell war bonds (debt securities to fund military operations), going on tour from January 1942 to September 1943. From 1944 to the end of the war Dietrich entertained American troops on USO tours in North Africa, Italy, France, and her former homeland. She shared the soldiers’ living conditions with rats, lice, and the sound of bombs falling, and sustained permanent frostbite damage to her hands and feet. In Dietrich’s autobiography, published first in German in 1978, she writes that when stationed within a mile of German front lines she feared the Nazis would “shave off my hair, stone me, and drag me through the streets.” Indeed, Neo-Nazis have been desecrating Dietrich’s grave since she was buried in Berlin beside her mother in 1993.

So, Dietrich was great. Now, imagine receiving love letters from her. Tender, passionate love letters.

This lady did:

That’s Mercedes de Acosta, an American writer from a Cuban family, eight years Dietrich’s senior. Acosta published three volumes of poetry, two novels, an autobiography, and had four plays produced. Her play Jacob Slovak, about anti-Semitism in a New England town, got rave reviews on Broadway in 1927; its London production featured top British actors Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud. Other productions were not successful, and when Acosta went to Hollywood to write for the moving pictures she hit a wall. That a woman playwright and screenwriter didn’t have a glorious career in a sexist culture should be no surprise, but accounts of Acosta’s life sometimes seem overly focused on her lack of sustained success—as if opportunities for women in film and theater were abundant in her time, or now. On this, we can let Gertrude Stein’s muse and noted cookbook writer Alice B. Toklas have the final word: “…you can’t dispose of Mercedes lightly,” she wrote to playwright Anita Loos, “she has had the two most important women in the US — Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich.” Eleanor Roosevelt would be my candidate for the most important woman in the US in the first half of the last century, but I said I would give Alice B. Toklas the last word so I’ll just leave that there.

In her autobiography, Here Lies the Heart, Acosta talks of seeing Marlene Dietrich at a dance recital in 1932, exchanging glances, and having her show up at her door the next day with white roses and an offer to cook for her because “You seem so thin and your face so white that it seems to me you are not well.” This odd start proved no obstacle to a passionate affair, any more than Dietich’s open marriage or Acosta’s lifelong obsession with Greta Garbo and her fondness, as recounted in Maria Riva’s Dietrich biography, for talking about Garbo more frequently than the weather. Later in life, and in need of cash, Acosta sold her archive of keepsakes from lovers and friends, including Dietrich, to the Rosenbach. The photos of Dietrich in this post are from Acosta’s collection; the double picture frame at the top of this page–with two glamour shots of Dietrich and candid shots by Acosta tucked in the corners–is typical of the way Acosta curated her memories. In addition to being criticized for not blossoming into a second Eugene O’Neil, Acosta is also criticized for fervently archiving her romances with glamorous women. But in a time when even Liberace couldn’t come out, the queer imagination, without mutilating itself, could only expand inwardly, like a chambered nautilus in reverse.

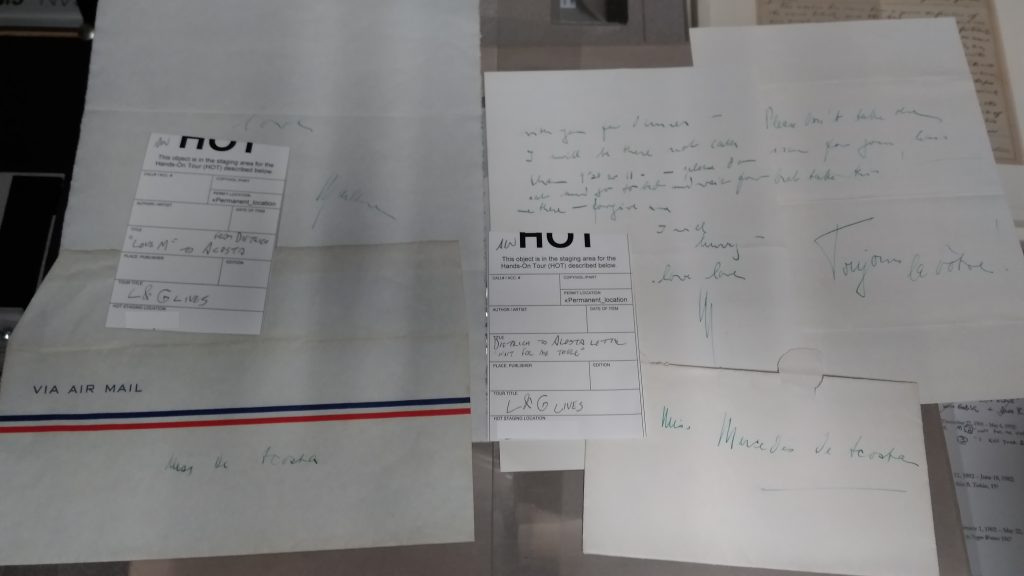

Robert A Schanke’s That Furious Lesbian: The Story of Mercedes de Acosta, tells how Acosta’s archive came to the Rosenbach. “I would not have had the heart or courage to have burned those letters…” Acosta wrote to the Rosenbach’s then-director, William McCarthy. “So it seemed a God-sent moment when you took them.” I apologize that the images below are not crisper, but as I am writing from home I’m relying on photos I took for research while preparing the Rosenbach’s Behind the Bookcase tour “20th Century Lesbian and Gay Lives.” Here, in the green ink all of Dietrich’s letters at the Rosenbach are written in, is the most sweetly concise love letter ever, a full sheet of paper saying only “love, Marlene.” To the right is page two of a breathless note in which Dietrich apologizes to Acosta for breaking dinner plans and says “I will be there not later than 9:30 or 10, please do eat and go to bed and wait for me there—forgive me, I will hurry— love love, M.”

“…go to bed and wait for me there.” Queer historical figures are often imprisoned in the pastel bigotry of willfully perceived ambiguity; we can be forever grateful to Dietrich for writing this unequivocally sexy letter.

Here’s another:

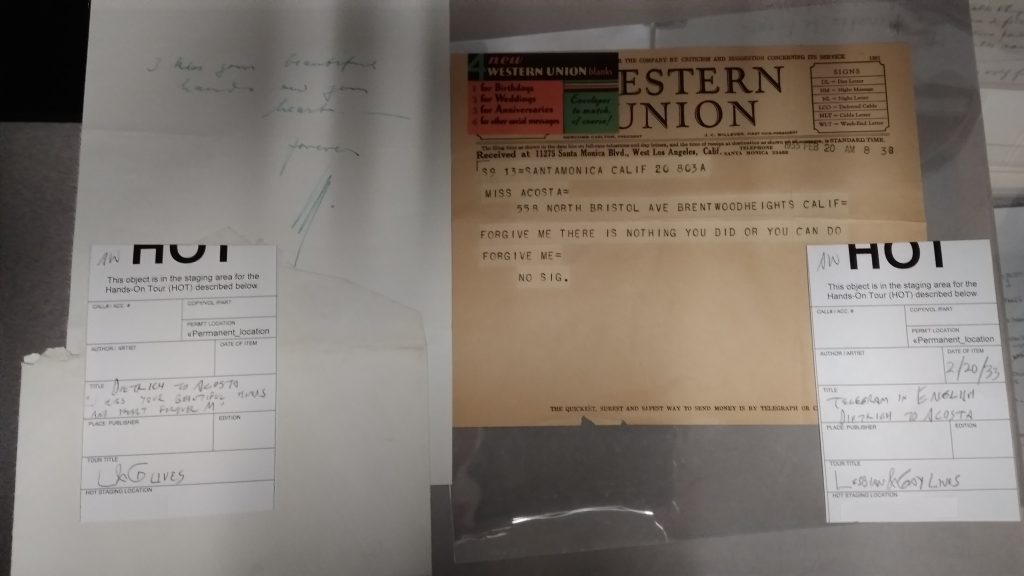

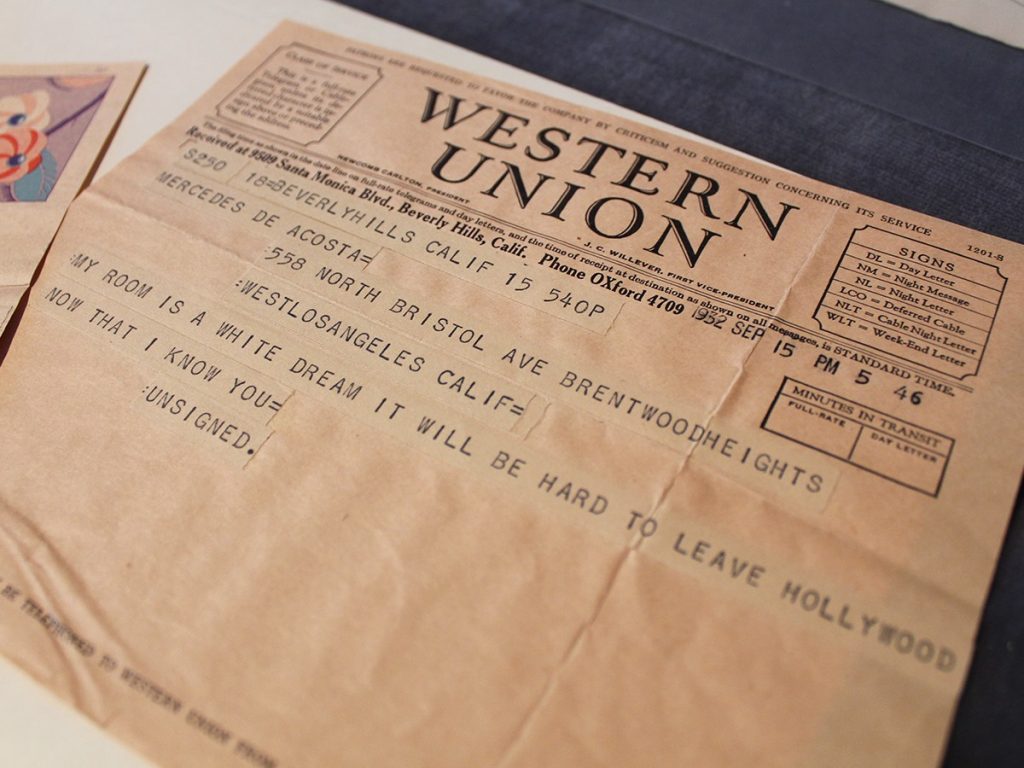

“I kiss your beautiful hands and your heart— forever, M.” And to the right, a breakup telegram so masterful in its fusion of kindness and finality it’s the Nike of Samothrace of breakups: “Forgive me there is nothing you did or can do forgive me.”

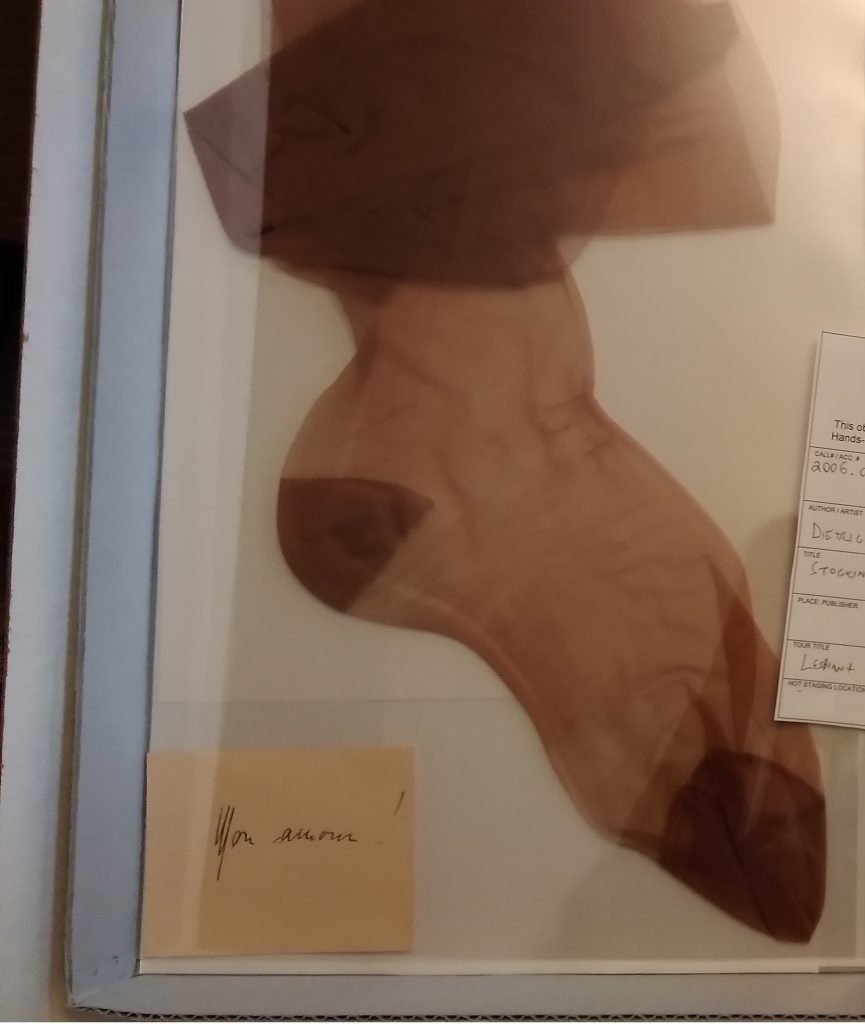

And below is one of our favorite objects at the Rosenbach: a note saying “Mon Amour!” that Dietrich sent Acosta along with one of her stockings:

As we contemplate the symbolism this stocking may have had for Acosta I would be remiss not to mention that Dietrich was renowned for having the greatest legs in Hollywood. Dietrich films often have a gratuitous shot of her taking off shoes or adjusting a stocking while we all, presumably, gawk; General Patton’s code name for Dietrich in World War II was LEGS; she began her act for the soldiers by poking one of these legendary limbs through the curtain; one of her stage bits when entertaining the troops was to hike up her skirt and play a musical saw. Here’s a publicity shot from The Song of Songs, a film Dietrich made the year she met Acosta:

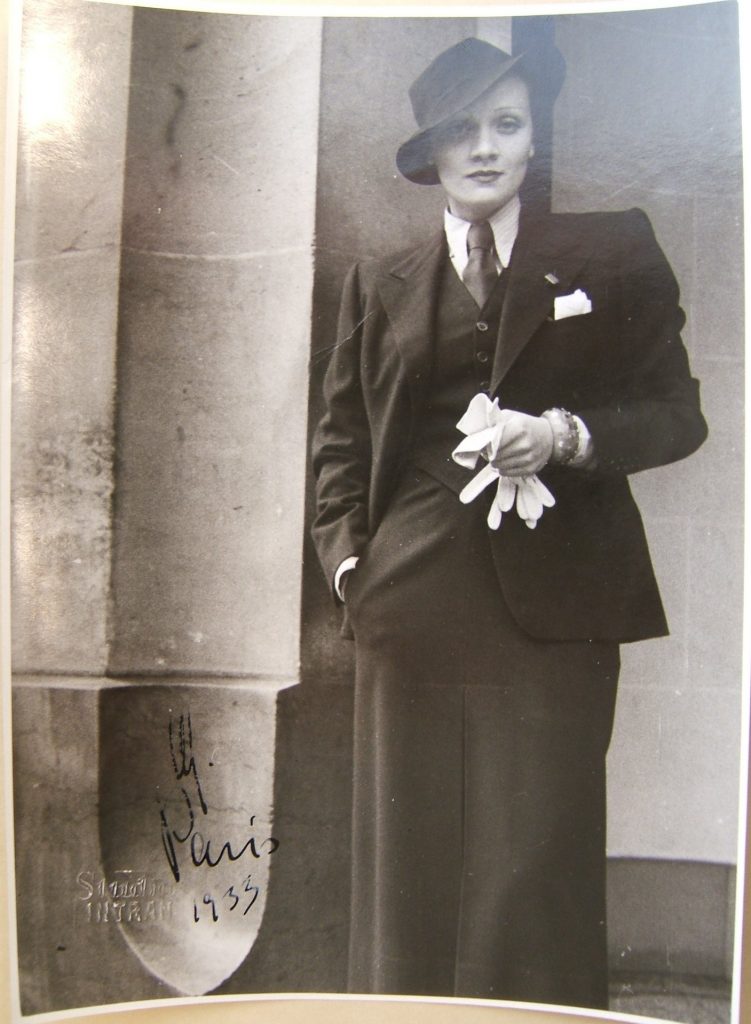

And from the same year, taken in Paris, with “für Mercedes” written on the back:

In Here Lies the Heart, Acosta takes the credit for getting Dietrich’s overhyped legs into trousers. In 1930’s Morocco, Dietrich had already proven that no one could rock a tux with greater aplomb, why not wear pants all the time? In this interview with CNN, historian Kate Clarke Lemay of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery talks about what happened when the Paris chief of police heard that Marlene Dietrich was heading for Paris in a white pantsuit.

From the year Dietrich and Acosta met, this one taken by Acosta:

“Sometimes I like entire towns or places just because I don’t ever have to get out of my jeans,” Dietrich wrote in Marlene Dietrich’s ABC, her 1962 book of proverbs, memories, and recipes.

Here she is in a white tux in Blonde Venus, 1932, just before she barged into Acosta’s life:

“Marlene sent me flowers sometimes twice a day, ten dozen roses or twelve dozen carnations, I was at a loss to know where to put them…. We never had enough vases and when I told Marlene this, as a hint not to send any more flowers, instead I received a great many Lalique vases and even more flowers.”

Mercedes de Acosta, from Here Lies the Heart

Register for Virtual Behind the Bookcase | 20th Century Gay and Lesbian Lives on Thursday, May 28 at 12:30 p.m.

Bravo! The best article to date on the website!

I love the art of the Writing in sentences like “ But in a time when even Liberace couldn’t come out, the queer imagination, without mutilating itself, could only expand inwardly, like a chambered nautilus in reverse.” how rare to make closeted affections seem nonetheless more beautiful than the simple clam shell of more familiar relationships.

Marlene is my idol!!!!!!!

Fascinating documents beautifully presented.