As I was stuck in traffic this week, a bright spot amid my frustration was hearing that NPR had picked Heart of A Samurai, a young adult novel about Manjiro, as their May selection for their “Backseat Book Club” for children. I haven’t read the novel, but I am excited that more young people will get to know the incredible story of this 19th-century Japanese teenager who traveled from Japan to the United States and then back again. His story is recounted in a fascinating non-fiction manuscript account here at the Rosenbach. We featured this manuscript in our 1999 exhibit Drifting: Nakahama Manjiro’s Tale of Discovery, (you can still buy the excellent catalog for this show) but I thought it wouldn’t hurt to highlight this Rosenbach treasure again.

Manjiro was a poor boy from a fishing village on the Japanese island of Shikoku. In 1841, when he was just fourteen years old, he and four fishing companions were caught in a storm and their boat was drawn into the Pacific Ocean and shipwrecked on the uninhabited island of Torishima. The group was ultimately rescued by the American whaling vessel John Howland, but since Japan was a closed country, they could not return home.

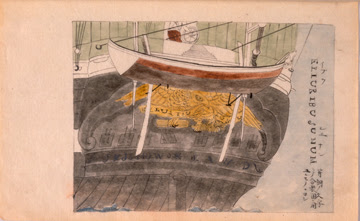

|

| Unknown artist, [stern of the John Howland], in Nakahama Manjiro, Hyōson kiryaku: manuscript, 25 October 1852 [Rosenbach Museum & Library AMs 1296/14] |

His four companions chose to disembark in Hawaii, but Manjiro had become close with the ship’s captain, William Whitfield, who treated him like a son, and so he returned with Whitfield to Fairhaven, Massachusetts. (You can see the Fairhaven locales associated with Manjiro in an online Manjiro walking tour brochure from the Manjiro/Whitfield Friendship Society) He spent the next ten years in America– attending school, working on a whaling ship, and eventually making enough money in the California gold rush to try and return to Japan in 1851 with two of his original companions.

Upon their return to Japan, the three men were interrogated by a series of officials for a year and a half before being allowed to return to their homes. Leaving Japan and returning were punishable offenses and there was also concern that the men might have converted to Christianity, which was also strictly prohibited.

During the interrogation period, Yamanouchi Yodo, the lord of Manjiro’s home province, had the artist Kawata Shoyo transcribe Manjiro’s account of his travels and add illustrations. Eventually multiple copies of the manuscript were made; nine copies are known exist today. The Rosenbach’s copy is one of only two in the United States (the other is in Fairhaven) and contains some additional drawings and English text in Manjiro’s hand.

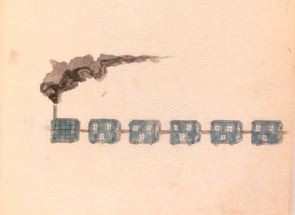

The manuscript is a fascinating document of a foreigner’s experience of America and also of the challenge of explaining a culture to someone who has never experienced it. One of my favorite illustrations is a four page picture of a train, which the Japanese artist depicts as a series of connected houses. You can see a detail of one of these pages below.

|

|

Unknown artist,

[railroad (detail)], in Nakahama Manjiro, Hyōson kiryaku: manuscript, 25 October 1852 [Rosenbach Museum & Library AMs 1296/14] |

Manjiro’s knowledge of English and of American culture would soon prove

useful in Japan when the Perry expedition arrived in July of 1853.

Manjiro was summoned to the capital at Edo, where he taught Japanese

officials about the United States and served as an interpreter. He

later served with the first Japanese embassy to the

United States, became an instructor of navigation, whaling,

and English,

and revisited Fairhaven after a twenty-year absence.

Manjiro’s story of cross-cultural connection and his love for America have resounded through the centuries. Manjiro’s descendents remained friends with Whitfield’s descendents and Manjro’s story has even inspired modern exchange initiatives. If your interest has been piqued, a complete English language translation of his tale was published in 2003 as Drifting Towards the Southeast. Happy reading.