Born on 8 December 1542 at Linlithgow Palace in West Lothian (Scotland), Mary was the daughter King James V of Scotland and his French-born wife Mary of Guise. King James V died pretty soon after her birth, and Mary was crowned Queen of Scots. Originally, there was a treaty with Henry VIII in which Mary would wed his son Edward, however Henry angered the Scottish parliament and they stopped the marriage by sending 5-year-old Mary to France. A new marriage agreement was set up between Mary and Francis, the heir of King Henri II of France.

In 1558, Queen Mary I of England died; Henri II encouraged his 15-year-old daughter-in-law to assume the royal arms of England. The majority of Catholic Europe at the time believed that Mary of Scotland was the true heir to the English throne as her cousin Elizabeth I was protestant and illegitimate. Less than a year later, King Henri II of France died and Francis and Mary were crowned King and Queen of France. Tragedy would strike again soon after with the deaths of both Mary’s mother and Francis, causing her to return to Scotland.

She returned to Scotland during a time of extreme religious turmoil. Scotland was protestant at the time, but Mary, a catholic, was determined that her Scottish subjects would be able to worship God however they saw fit. She also was determined to strengthen the crown against the Scottish nobility, who were notoriously difficult. She became popular among the common people, but, quite obviously, not among the nobility.

In 1565, she wed a noble cousin named Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley. He was strongly disliked by the common people of Scotland. In March of 1566, when Mary was sixth months pregnant, Darnley and a number of other Scottish nobles stabbed her Piedmontese secretary, David Riccio, to death, claiming that he had undue influence over Mary’s foreign policy. It is suspected that they had meant Mary to suffer a miscarriage and die from watching the horrific crime, thus making Darnley King, but nothing is known for sure.

After Riccio’s death, Mary was kept prisoner at Holyrood Palace by members of the nobility. However, she managed to escape just a few months later with the surprising help of Darnley. Eventually, the future James VI of Scotland, Darnley’s son, was born. Two years later, the nobles who Darnley had plotted with in the murder of David Riccio, had Darnley’s house blown up. Darnley was found strangled in the garden.

James Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell, was implicated in the murder. However, she consented to marrying him, hoping to finally stabilize the country, however it did not work. The nobles were still angry and waged war against Bothwell in 1567. Mary, to avoid bloodshed, turned herself over to the rebels and was taken to Lochleven Castle and forced to abdicate in favor of her son.

In 1568, Mary managed to escape Lochleven and began to make her way south to ask her cousin Elizabeth I for support. Elizabeth wasn’t exactly the most welcoming. She had been helping Mary’s enemies, promising them money and sanctuary in return for conspiring against Mary. Mary was the closest Catholic claim to the throne and Elizabeth, a protestant, didn’t really like that. When Mary arrived in England, Elizabeth had her guarded and then moved around from prison to prison.

|

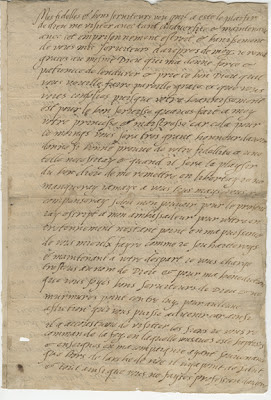

| Mary, Queen of Scots, autograph letter. Sheffield castle, [18 September 1571]. MS 569/12. The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia |

It is during this time where our letter comes into the picture. Our letter was written in 1571 while Mary was interred in Sheffield Castle. In it, she is writing to friends who have been banished from her. She, in particular, mentions a Master Gordon and a Master William Douglas. William was said to have helped her escape from Lochleven Castle. She begs them to urge the King, the Queen and Monsieur to help her poor subjects in Scotland and says that if she were to die, she would wish the King of France to protect her son and friends according to the ancient league of France with Scotland.

On 8 February 1587, Mary was executed at age 44 in the Great Hall of Fotheringhay. She was executed under suspicion of plotting to kill Elizabeth and claim the English throne. Sixteen years later, however, Mary’s son became King of England and Scotland and moved her body to Westminster Abbey.

The Rosenbach’s letter by Mary shows her devoutness to her religion, and, especially, her devotion to those who she considered friends and family. Most of this side of Mary is overlooked in favor of her relationship with Elizabeth as well as all of the drama that surrounded her early life. The Rosenbach’s letter, however, gives us a chance to see a different side of Mary whose primary concern is for the safety and wellbeing of those she cares about.

Allison Darhun is a collections intern at the Rosenbach this

summer and a History major at St. Joseph’s University.