As the opening date for Frankenstein & Dracula approaches, we’ve been revisiting some of the strange (and occasionally salacious) stories from the lives of the Romantic authors whose dark and imaginative stories inspired two of history’s greatest monsters. A favorite among our staff is the grim tale of Percy Shelley’s heart. When he was just shy of 30 years old in 1822, Percy Shelley and two fellow sailors tragically drowned during a boat trip across the Ligurian Sea; their bodies washed ashore ten days after a serious storm. Several of Shelley’s friends–novelist Edward John Trelawney, poet Leigh Hunt, and the inimitable Lord Byron–went to claim the remains and were obliged to cremate the unfortunate sailors so the ashes could be sent to their families. (It must be admitted that the writers were very taken by poetic and Hellenic connotations of a funeral pyre; they even anointed their lost friends with oil and wine as they imagined the ancient Greeks would.) For reasons that are not known, Shelley’s heart remained whole instead of turning to ash in the fire, and Trelawney retrieved it from the flames (burning his hand in the process). The heart was eventually given to Mary Shelley, who reputedly kept it in her desk until her death thirty years later.

We are fascinated by this story, gruesome as it is, because it seems quintessentially Romantic: the death of a tragically young poet; the pyre on a wild, windswept beach; the supernatural and symbolic indestructibility of Shelley’s heart. (In fact, the almost legendary significance of this literary relic is one of the topics of a forthcoming talk given by Ernest Hilbert at the Rosenbach.) But since today would be Mary Shelley’s 220th birthday, we turn our attention instead to the symbolism of Mary Shelley keeping the heart in her desk, the center of her literary output, for the rest of her life.

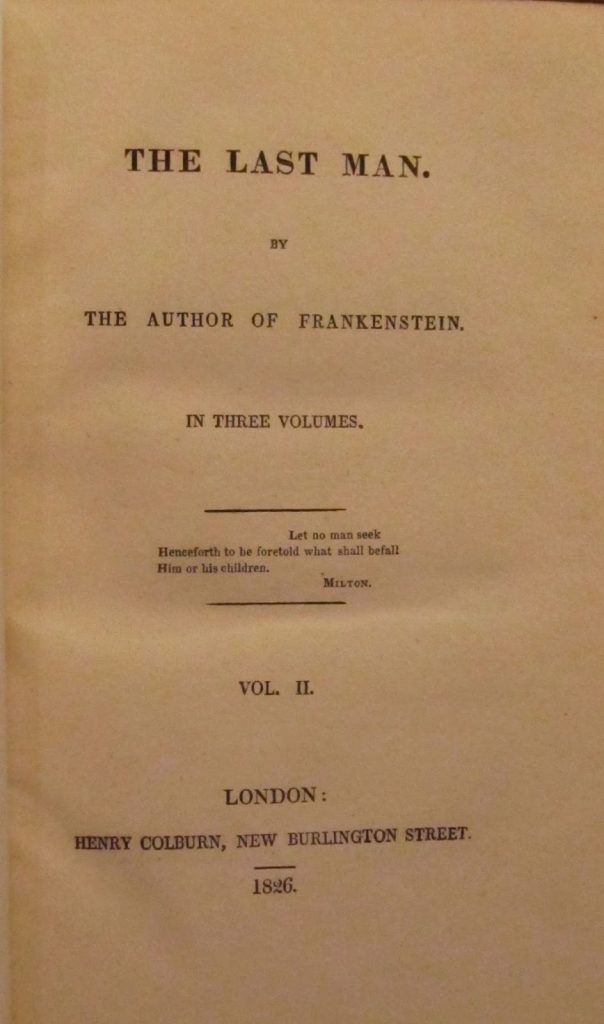

Mary Shelley may be best known as the author of Frankenstein, a novel that famously originated during a stormy summer Mary and Percy spent with their friend Lord Byron, Byron’s doctor John Polidori, and Mary’s step-sister Claire Clairmont. But literature was her life’s work, and her publications were wide-ranging and well-respected during her lifetime. She edited her husband’s poetry for posthumous publication, and transcribed Lord Byron’s poems for several years after Percy Shelley’s death. She published historical novels that delved deeply into past political conflicts such as land wars in fourteenth-century Italy and conflicts of succession in the English court of Henry VII. She penned intimate family portraits, including Mathilda, Falkner, and Lodore, which explored the education of daughters and troubled relationships with fathers. She wrote extensive journals and travelogues as she journeyed across Europe with her only surviving child, Percy Florence Shelley. She also wrote what is now considered one of the first post-apocalyptic novels: The Last Man, which follows a dwindling group of survivors as a plague wipes out the population of Europe.

This body of work is all the more remarkable in light of the losses Shelley suffered during the same period. The early years of her life with Percy Shelley were troubled; though their Romantic peers espoused utopian ideals of an authentic life unfettered by the shackles of society, they nonetheless struggled with debt, constant relocation, and jealousy. (Searing portraits of these peers may be found in The Last Man, among other writings.) As they moved from place to place, they traveled across a Europe still scarred by the Napoleonic wars. (The political implications of these wars are obliquely addressed in her historical novel Valperga.) During this precarious time, the Shelleys endured the losses of Mary’s half-sister, Percy’s first wife, and the Shelleys’ first three children together–which sent Mary into long periods of depression. (It was during one of these periods of mourning that Mary wrote Mathilda.) Mary Shelley was only 25 when she learned of her husband’s death; their young son was about four years old. A few years later, nearly everyone who surrounded her during that fateful Frankenstein summer–her husband, Polidori, Byron, Byron and Claire’s young daughter–were gone.

On the surface, the story of Percy Shelley’s heart seems like a symbol of poetic expression and a deeply romantic (if morbid) gesture of true love. But the subject of this blog post is actually Mary Shelley’s heart–not the literary relic she kept in the desk where she wrote, but her own indestructible center from which a lifetime of innovative writing and literary influence emerged. Mary Shelley’s legacy was to make something enduring and meaningful out of pain and loss–an equally powerful symbol.