This blog post was written by Andrew White

January 25 is Burns Night, when we celebrate the works of Scottish poet Robert Burns, the Bard of Ayrshire. It’s also a tradition here on Delancey Place, where our celebration features a night of readings, music, and whisky.

The Rosenbach is home to the largest extant collection of Burns’s letters, manuscripts, and early editions. Learn more below about the story behind the collection, and about one of Burns’s most famous poems, “Tam o’Shanter.”

In Among Old Manuscripts, an essay in his 1927 collection Books and Bidders, Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach wrote of his dealing and collecting adventures: “…there are compensations in this game if you have the patience to wait.” Case in point: after missing his chance to acquire the legendary Glenriddell Robert Burns collection, Dr. R. secured what he called “probably the greatest collection of Burns manuscripts…” confessing that he kept this collection ”under lock and key in my vault… lest the whole Scottish nation awaken one day, rise up, and demand them.” These prized Burns relics had belonged to the department store magnate and bibliophile R.B Adams, and—to Dr. Rosenbach’s great good fortune—was auctioned in 1924 by his nephew and heir, also named Robert Adams, so that the Adams collection could be focused on its greatest strength, Samuel Johnson.

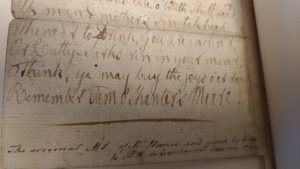

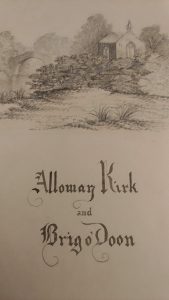

In describing the wonders of his newly acquired Burns collection, Dr. R. wrote, “Perhaps the foremost is the original draft of ‘Tam o’ Shanter,’ written on twelve leaves, which Burns presented to Adam Cardonnel-Lawson in 1790.” This is one of three “Tam o’ Shanter” manuscripts known to exist, and is neatly bound into a book; you see it on the left in the picture above. Along with the manuscript, this unique tome combines background on the setting of Burns’s famous supernatural tale, and drawings by the aforementioned Cardonnel-Lawson—a Scottish artist and antiquarian, and acquaintance of Robert Burns. Below is Cardonnel-Lawson’s drawing of the ruined Alloway Church, where Tam o’ Shanter spies on a witches’ convocation, and the bridge over the river Doon, where he makes his escape:

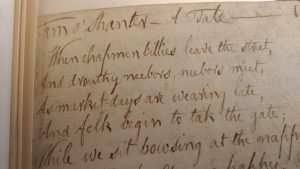

Considering the bacchanalia that takes place in the Alloway Kirk in Burns’s poem—and the desperate Ichobod Crane-style escape Tam makes over the Doon—Cardonnel-Lawson’s image is disappointingly tranquil, though useful for setting the scene. Here’s something that should give you the appropriate chills—whether you’re a fan of Robert Burns, classic tales of the uncanny, or both: the first lines of “Tam o’Shanter,” in Burns’s hand, from the Rosenbach’s manuscript:

In these opening lines, Burns describes the winding down of a market day as peddlers pack up their wares and neighbors shoot the breeze and go home, or stop by to the pub, like the titular Tam:

When chapmen billies leave the street,

And drouthy neibors, neibors meet,

As market days are wearing late,

An’ folk begin to tak the gate;

While we sit bousing at the nappy…

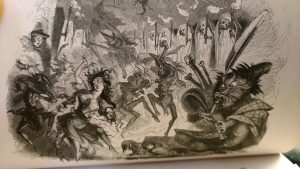

“Bousing at the nappy” here is to drink strong ale—potentially the source of Tam’s troubles later. If Tam o’ Shanter had been sober when he rode past a witches’ rave in the ruined Alloway Kirk, he might have had better control over his tongue and not whistled at a witch in a short chemise (or “cutty sark”). Here’s the pagan conclave Tam intruded upon, in the Rosenbach’s 1830 edition of “Tam o’ Shanter,” illustrated by Thomas Landseer:

On the far left is Tam o’Shanter, wearing the hat to which he will give his name, creepily spying on the party of witches and demons to which—the mannerly reader will note—he was not invited. In the left foreground is Nannie, a young witch who becomes the catalyst for Tam’s dramatic flight from the scene. On the right is the devil himself, in the form of a giant bagpipe-playing dog—certainly the most charming avatar of bestial diabolism I’ve encountered since the Flyers debuted Gritty. In Burns’s words:

Warlocks and witches in a dance;

Nae cotillion brent-new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs strathspeys, and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

A winnock-bunker in the east,

There sat auld Nick, in shape o’ beast;

A towzie tyke, black, grim, and large,

To gie them music was his charge:

He scre’d the pipes and gart them skirl,

Till roof and rafters a’ did dirl.–

Tam obnoxiously blows his own cover by “complimenting” Nannie on the shortness of her shift (“Weel done, Cutty-sark!”). In response, Nannie leads the infernal horde in a wild chase to capture Tam. Disappointingly, Tam makes it to safety by passing the keystone of the Doon bridge (or, “Brig a’ Doon,” from which the Broadway show may have taken its name). In an ending that seems particularly unjust to this reader, Tam’s savior is his stalwart mare, Maggie, who takes his punishment by having her tail ripped out just as she’s galloping Tam to safety. Here’s the Landseer illustration of the climactic scene:

To Tam’s credit, he does look more alarmed at the fate of Maggie’s tail than he is at the proximity of a supernaturally empowered sorceress bent on revenge. Even so, I might have preferred to see Nannie and her friends drag Tam to hell. The dubious moral Burns appends to his eldritch romp reads as follows:

Now, wha this tale o’ truth shall read,

Ilk man and mother’s son take heed;

Whene’er to drink you are inclin’d,

Or cutty-sarks run in your mind,

Think! ye may buy joys o’er dear –

Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mare.

And, the denouement in Burns’s own hand: