This week’s blog post is again courtesy of Emelye Keyser, the Rosenbach collections intern who wrote a previous post on Rudimentum Novitiorum. Given that Emelye came to the Rosenbach after graduating from the University of Edinburgh, we couldn’t resist asking her to write a piece for tomorrow’s Burns night.

Chaucer had done for English nearly four centuries before: he

proved it to be capable of sophisticated poetry and he put his country on the

literary map. He penned universal truths

– ‘a man’s a man for a’ that’ and ‘the best-laid schemes of mice an’ men / Gang

aft agley’ – using the hitherto little-acknowledged (or understood) vernacular,

and compelled the English to sing in his language every New Year’s Eve with

‘Auld Lang Syne.’ The Rosenbach will be celebrating

the 254th birthday of Scotland’s Bard on Friday the 25th of January, and where

better to raise a glass of Scotch to Rabbie than the resting place of one of

the earliest Tam o’ Shanter manuscripts!

|

| Robert Burns, “Tam O’Shanter”: autograph manuscript. [1790]. EL2 .B967 MS3 |

“Tam

O’ Shanter” celebrates Scotland’s culture, folklore, and landscape. Yet its themes are recognizable and appealing

to all: the tribulations of returning home from drinking; the supernatural

horrors of woodlands at night. Set in

the coastal town of Ayr, southwest of Glasgow, the poem recounts the

adventures of Tam as he rides his faithful mare, Maggie, home from the pub late

one stormy night. Hearing a commotion

coming from within Alloway Kirk, Tam approaches a window and watches as party

of ‘warlocks and witches’ dance about the church. He is spotted when he can’t help applauding a

particularly comely demon and is chased through the night by her, finally escaping

when he crosses a stream – though poor Maggie makes less of a clean getaway

than her master!

allegedly wrote “Tam O’ Shanter” at the request of Francis Grose, who in 1790

was completing his Antiquaries of

Scotland. Burns met Grose and Adam

Mansfeldt de Cardonnel-Lawson, both amateur antiquarians, at Friar Carse, the

home of a mutual friend; the poet asked Grose to include Alloway Kirk in his

book, and Grose in turn promised to do so if Burns would pen a story about the

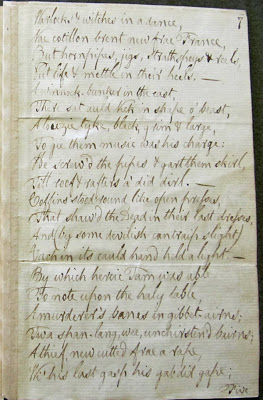

place. The Rosenbach’s “Tam O’ Shanter”

is the manuscript that Burns sent to Cardonnel-Lawson several days after they

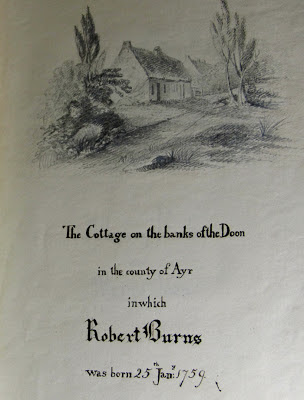

met. Some time in the early nineteenth

century Cardonnel-Lawson’s son had it bound with material that reflected the

story of its conception: alongside “Tam” there is a picture and hand-written

description of Friar Carse, a portrait of Burns, a pencil drawing of Burns’

birthplace, a drawing of Alloway Kirk, and a short essay on the kirk that

borrows heavily from the published description in Antiquaries of Scotland. The

poem has since been cut from its binding, and in the pictures below it appears

as loose-leaf.

|

| Robert Burns, “Tam O’Shanter”: autograph manuscript. [1790] EL2 .B967 MS3 |

|

| Robert Burns, “Tam O’Shanter”: autograph manuscript. [1790] EL2 .B967 MS3 |

“Tam

O’ Shanter” can be a challenging read, written as it is in 18th-century Scots.

Several English translations exist, but the power of the language is compromised:

best to read the poem in the original with the English

alongside it. Some tips from an

American who lived in Edinburgh: “ken” is the Scottish word for “know” and is

never conjugated; “unco” can mean “strangely,” “remarkably,” or “a lot”; and

almost all other unfamiliar expressions stand for alcohol or those who enjoy

it!

best way to enjoy “Tam” is not to read it, but to listen to it, either here

or tomorrow evening at the Rosenbach’s celebration!

Emelye

Keyser is a graduate of the University of Edinburgh and is currently

interning in the collections department of the Rosenbach Museum &

Library.