I remember as a child being fascinated with my baby book; I would periodically pull it off the shelf in my mother’s study to look at it and compare it with my brother’s. When I became a parent, I, in turn, bought baby books for my children, although I wasn’t always consistent in filling them out. But how often do we look at other people’s baby books? Robert Louis Stevenson’s baby book has been preserved for posterity due to its 1922 publication by fine-press printer John Henry Nash in an edition of 500 copies.

The introductory text by Katherine D. Osbourne, the wife of Robert Louis Stevenson’s stepson, claims that

This Baby Record was meant by the young mother who wrote it as all such Records are to keep for memory’s sake an account of the first years of her adored child, A few of the notes were added by her in later years…. With every passing year this Baby Record grew a more precious possession to the mother.

However, a closer look indicates that something more complicated must be going on. The baby book involved is Baby’s Record by Reginald Illingsworth Woodgouse (R.I.W.), which seems to have come out in 1889. ” So although the notes inside are detailed, they must have been copied into the baby book from an earlier source sometime near the end of Stevenson’s life, or even shortly afterward (he died in 1894 and the book was still available then; his mother died in 1897)

It seems that commercial baby books weren’t really available in 1850, when Stevenson was born. The earliest example in the baby book collection at UCLA is from 1882 and the librarian there notes that it “feels like a new, unfamiliar phenomenon…it includes a ‘specimen page’ that shows the parent how to fill

in the blanks.” Similarly, an advertisement for Baby’s Record from 1889 seems to need to explain what it’s for.

But parents certainly kept notes on their children even before there were special books for the subject. Maria Edgeworth’s Practical Education recommends “writ[ing] notes from day to day all the trifling things which mark the progress of the mind in childhood” as an important means for putting proper educational processes into practise, although she cautions that children shouldn’t see the notebook because it would make them self-conscious. She records a number of anecdotes, such as “Y (a girl of three years and a half old) seeing her sister taken care of and nursed when she had chilblains, said, that she wished to have chilblains”. An alphabet book in the Cotsen collection at Princeton was annotated by a mother who recorded how her son explained each picture.

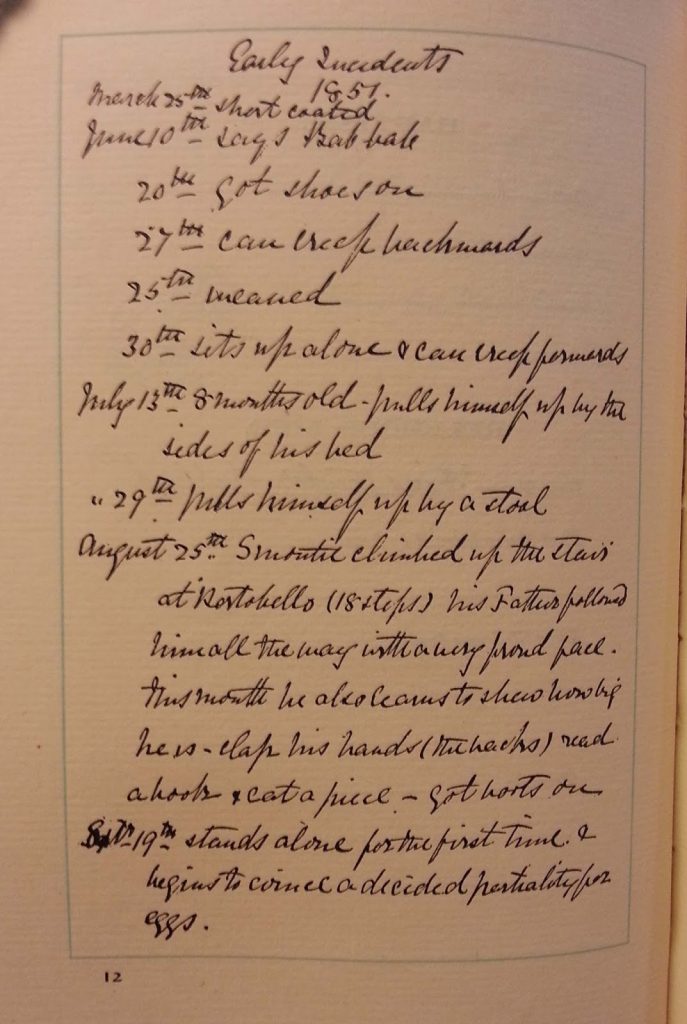

Back to Stevenson. Looking through the book, it seems that when his mother transferred her earlier notes from wherever she had kept them into this commercial baby book she was less interested in filling out all of the pre-printed milestones than in using the book’s many journal pages to record more free form entries of little Lou’s childhood. She does record his first journey, first crawl, and first steps in the “proper” places, but the section on his favorite foods is blank, although she notes elsewhere that he “[began] to evince a decided partiality for eggs” at around 10 months. (See below)

Obviously since Stevenson grew up to be an author, one of the fun parts of looking through the book is finding early references to books and reading. On the same page as the note about eggs, his mother noted when Stevenson was 10 months old that “this month he also learns to shew how big he is— clap his hands (the backs) read a book and eat a piece- got boots on. ” A year later he had been introduced to Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s: at the age of 23 months “Smout knows all the story of Eve and Uncle Tom, besides a great many out of the Bible, including the flood and the burning bush. He remembers them wonderfully well. When he was four years old “Lou dreamt that “he heard the noise of pens writing.”

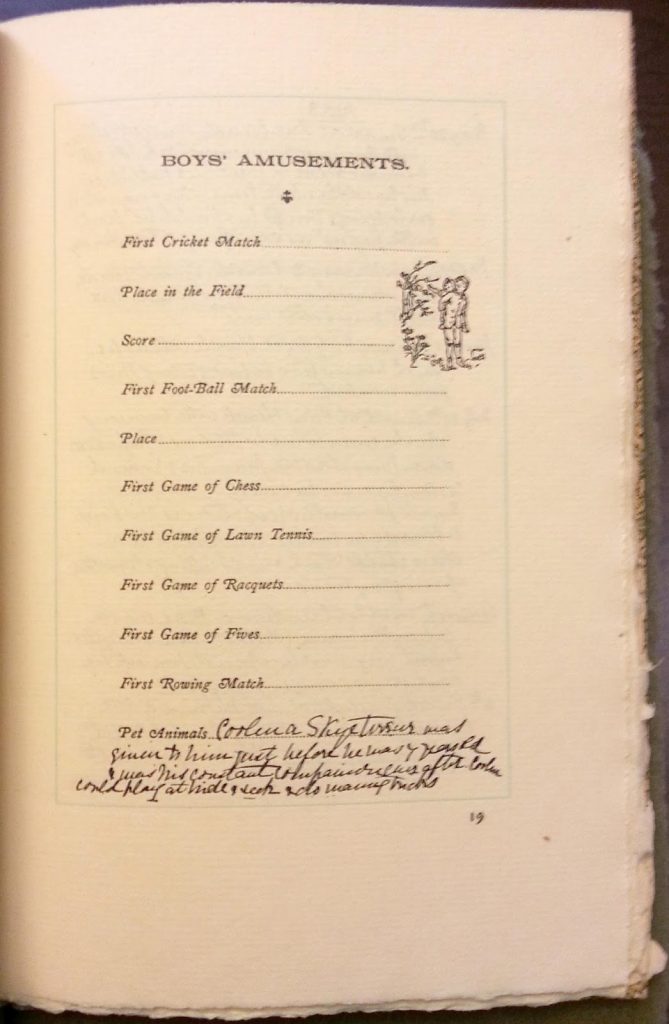

In addition to the Stevenson content, I found the book itself interesting as an element of the material culture of childhood. Baby’s Record, unlike many in the UCLA collection, which were sponsored by baby food or banks, does not appear to be linked to advertising. But I was interested to see that it was clearly gendered and also clearly aimed at a well-to-do audience (who I guess were willing to buy a book rather than get a baby food handout version), as evidenced by an

(unused) page for “Boys’ amusements” that included spaces for recording

“First cricket match,” “First game of chess,””First game of lawn tennis” and “First rowing match,” among others.

In the end, I still have a lot of questions about this book, especially regarding when and why the recollections were transferred in. Did it have to do with Stevenson’s death? Were baby books suddenly fashionable in the 1890s and lots of people created them ex-post facto for their children? If anyone reading this post know more about this, I’d be fascinated to learn.