I’m Emelye, a new intern here with an inclination towards all things medieval. This week I want to share little bit about a particularly impressive item in the Rosenbach’s incunabula collection. Titled Rudimentum Novitiorum, this book was printed in Lübeck, Germany in 1475 – one year before the printing press even came to England. The work’s author remains unknown, but its purpose is evident: it was intended as a textbook for novice monks and expounds the history of the world, beginning with Creation and weaving its way down through contemporary events.

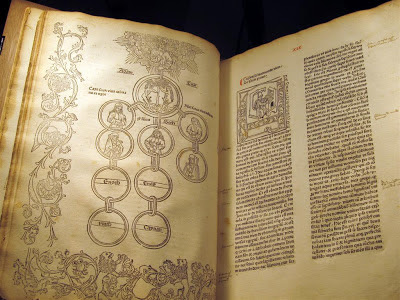

The Rudimentum Novitiorum is a formidable object. I thought my high school calculus book had been bad: I pity the monk who had to lug this thing around. Elizabeth (the Rosenbach librarian) and I wrestled the 16.5 x 12 x 5 inch, 950-odd page volume, in its modern wood binding, into the research room and heaved it gently onto a cradle. This is what we opened up to:

|

| Rudimentum Novitiorum. Lubeck: Lucas Brandis, 1475. Rosenbach Museum & Library Incun 475r |

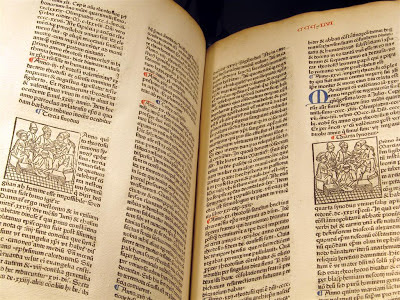

The script is beautifully printed in Latin, and has been well-studied, judging by the hand-written annotations in the margins. The numbers at the tops of the pages have also been hand-written in red ink, and most openings have one or more woodcuts adorning the text – though the photo below catches the printer in the act of using the same woodcut to illustrate two different stories. Above, on the left hand page, Adam and Eve’s immediate descendants are mapped; on the right hand page a scribe sits within a letter A.

|

| Rudimentum Novitiorum. Lubeck: Lucas Brandis, 1475. Rosenbach Museum & Library Incun 475r |

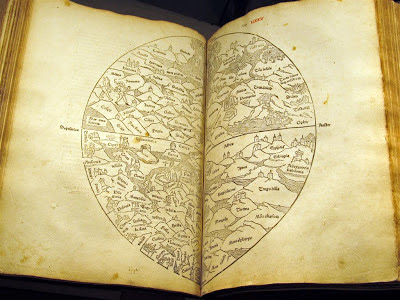

The most exciting thing about this volume is the inclusion of the first printed world map (excluding very simple T-O diagrams of the earth):

|

| Rudimentum Novitiorum. Lubeck: Lucas Brandis, 1475. Rosenbach Museum & Library Incun 475r |

Printed using two half-circle woodcuts, one on each page, the map may have been done using new technology, but it embraces many medieval conventions. East – rather than north – is at the top of the page (you can just make out the word ‘orient’), and the map is divided into three continents, with Asia spanning the entire upper half of the world. Jerusalem is at the center, largely lost in the crease of the book. Priority is placed upon the spiritual importance of a place – thus Jerusalem is nearer to Rome than to Greece – and upon the inclusion of important landmarks, rather than parsing out their geographical locations and relationships.

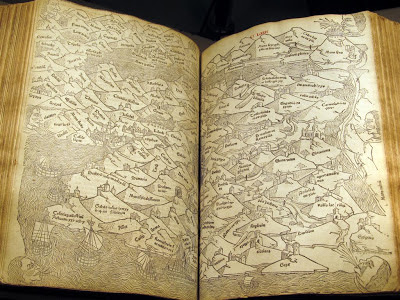

The historian V. Tooley wrote that “it is unwise to assume that medieval scholars were as ignorant as their maps would imply. Their aim might be, and probably was, symbolic and moral rather than utilitarian.” Medieval maps were not meant as travel guides: check out the map of the Holy Land, below, which emphasizes the connection between locations and specific Biblical lines:

|

| Rudimentum Novitiorum. Lubeck: Lucas Brandis, 1475. Rosenbach Museum & Library Incun 475r |

If this approach seems impractical, rest assured: others at the turn of the sixteenth century felt the same way. Within a few years of Rudimentum Novitiorum, printed versions of Ptolemy’s Geographia appeared including maps based on Ptolomy’s model and mapmaking changed forever.

Emelye Keyser is a graduate of the University of Edinburgh and is currently interning in the collections department of the Rosenbach Museum & Library.