More and more information is finally being released about Philadelphia’s plans for the upcoming papal visit in a month’s time, but given all the swirling logistical questions and potential transit snafus, it seemed like an appeal to St. Christopher might not be out of order. The traditional patron saint of travelers, St. Christopher was supposedly a third century martyr under Decius, but little is known about his life or death and there is no solid evidence that he actually existed, which contributed to his being removed from the Catholic Church’s universal calendar of feasts during 1969 reforms.

Despite a lack of solid facts about Christopher, the Roman Calendar states that “the existence of his cult is very old.” The earliest sources focus on his martyrdom, but by the middle ages many colorful legends had grown up around Christopher and were preserved in books such as The Golden Legend.

The Golden Legend was one of the most popular books of the medieval period. Written in Latin by the Dominican friar Jacobus de Voraigne around 1260, a thousand manuscript copies survive in a wide range of European languages. After the development of printing, Jacobus’s book still topped the best-seller list; a 1471-2 edition by Günther Zainer was the first “printed book to be extensively illustrated” and between 1470 and 1500 there were over 150 printed editions, as compared with 128 editions of the Bible.

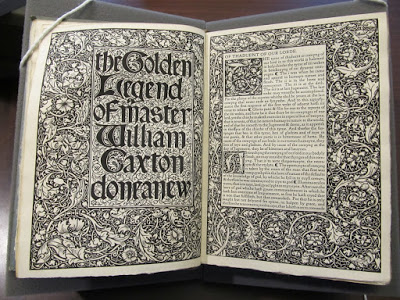

In 1483 William Caxton translated and printed an English edition of The Golden Legend, based on Latin, French, and English versions of the text. It was his largest work, requiring at least 15 months to translate, running to 898 pages, and incorporating 70 woodcuts. Over four hundred years later William Morris’s Kelmscott Press produced a beautiful three-volume edition of Caxton’s text, with new illustrations by Edward Burne Jones. Morris had actually wanted it to be the first book to come from Kelmscott, but the length of the work taxed him as it had Caxton and so it turned out to be the seventh, published in 1892.

|

| Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend. Hammersmith : Kelmscott Press, 1892.

FP .K29 892v. The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia

|

This brings us back to St. Christopher.

|

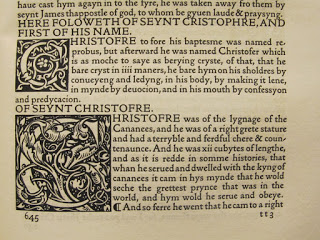

| Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend. Hammersmith : Kelmscott Press, 1892.

FP .K29 892v. The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia |

The Golden Legend likes to start its hagiographies with a discussion of the saint’s name, and Christopher is no exception. His introduction reads (in modern English taken from this transcription)

Before his baptism was named Reprobus, but afterwards he was named Christopher, which is as much to say as bearing Christ, of that that he bare Christ in four manners. He bare him on his shoulders by conveying and leading, in his body by making it lean, in mind by devotion, and in his mouth by confession and predication.

The idea that Christopher “bare [Christ] on his shoulders” is the most popular story about the saint and the one that gave him his role as the patron saint of travelers. Here is the version told in The Golden Legend.

|

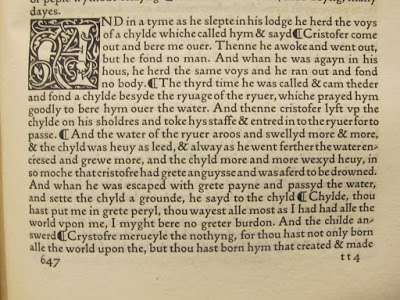

| Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend. Hammersmith : Kelmscott Press, 1892.

FP .K29 892v. The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia |

Christopher sought out a hermit to be instructed in the faith and the hermit asked him to serve God through fasting; Christopher asked if there was another way. The hermit suggested “wak[ing] and making many prayers,” but Christopher didn’t like that any better and so the hermit told the giant Christopher (who was 12 cubits–18 feet–tall) to serve God by carrying passengers across a dangerous river. This was acceptable:

And there he abode, thus doing, many days. And in a time, as he slept in his lodge, he heard the voice of a child which called him and said: Christopher,

come out and bear me over. Then he awoke and went out, but he found no

man. And when he was again in his house, he heard the same voice and he

ran out and found nobody.

The third time he was called and came thither,

and found a child beside the rivage of the river, which prayed him

goodly to bear him over the water. And then Christopher lift up the

child on his shoulders, and took his staff, and entered into the river

for to pass.

And the water of the river arose and swelled more and more:

and the child was heavy as lead, and alway as he went farther the water

increased and grew more, and the child more and more waxed heavy,

insomuch that Christopher had great anguish and was afeard to be

drowned. And when he was escaped with great pain, and passed the water,

and set the child aground, he said to the child:

Child, thou hast put me

in great peril; thou weighest almost as I had all the world upon me, I

might bear no greater burden. And the child answered:

Christopher,

marvel thee nothing, for thou hast not only borne all the world upon

thee, but thou hast borne him that created and made all the world, upon

thy shoulders. I am Jesu Christ the king, to whom thou servest in this

work.

So if you’re planning on coming from New Jersey to see the pope in September and aren’t up for walking over the closed Ben Franklin bridge, perhaps a ride from Christopher across the Delaware would be a better bet? Or of course there’s always PATCO…