This blog post was written by Andrew White

Because we don’t know when Shakespeare was born, only that he was christened on April 26, 1564, we agree to assume he was born a few days before that on April 23rd. We have a better idea of what Shakespeare looked like. Both the engraving in the First Folio, his collected plays, published seven years after his death, and the sculpture on the funerary monument in his hometown of Stratford were commissioned by people who knew and loved him and would have wanted their money back if his posthumous portrait didn’t look like him. Accurate they may be, but neither likeness is particularly alluring. Both show a dead-eyed man whose expression reads as: “slightly annoyed by unwelcome interruption.” Shakespeare’s Tinder profile would be doomed to perpetual leftward swipes.

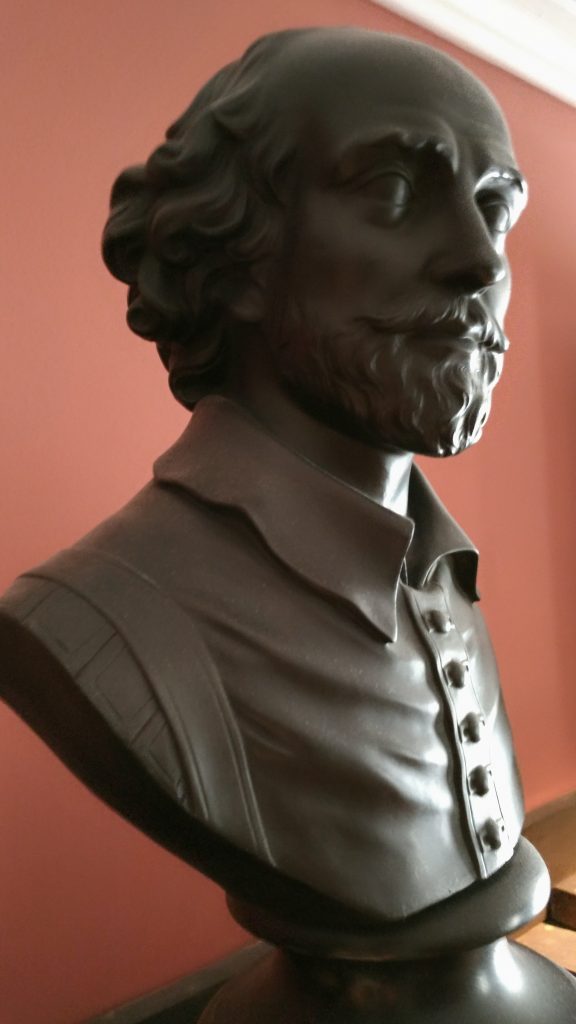

The portrait bust of Shakespeare at The Rosenbach— dashing, elegant, with a slight smile and raised eyebrow suggesting rakish good humor—resembles how Shakespeare might have wished to look. We don’t know the exact date of the bust, just that it was made by Wedgewood no later than 1776, and is black basaltware—which, to my disappointment, contains no actual volcanic rock. The bust sits atop a bookcase where many of the early quartos of Shakespeare’s plays also reside, along with some early Shakespeare criticism, and at least one book from which Shakespeare may have cribbed a plot or two.

Two of these books provide a look at how Shakespeare was seen by his contemporaries. One of these, Francis Meres, thought the world of him. The other, Robert Greene, thought Shakespeare was uppity, full of himself, and an all-around bad character.

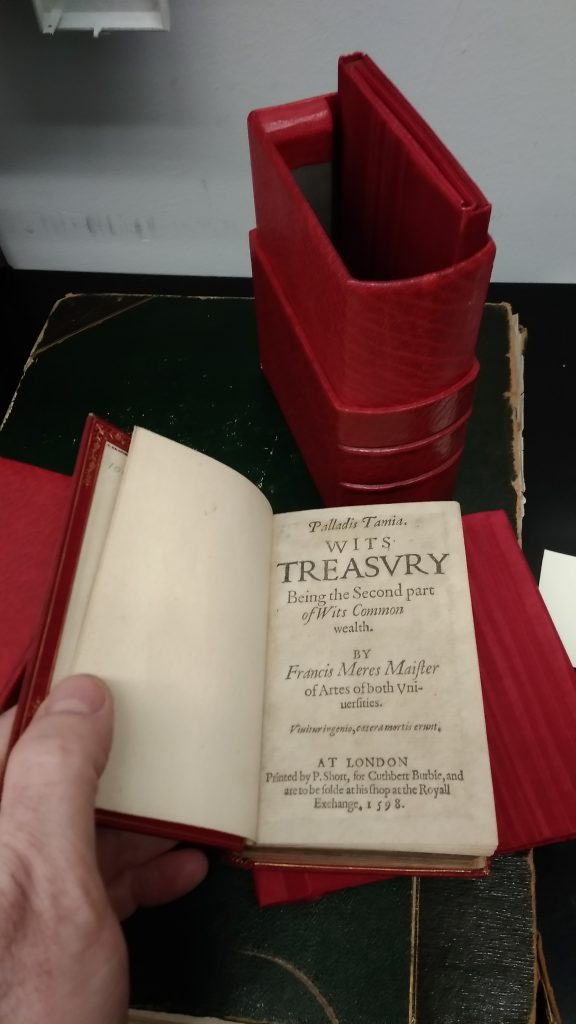

Let’s look at Shakespeare’s nice contemporary first:

That’s a 1598 first edition of Palladis Tamia, or Wit’s Treasury written by Francis Meres, a clergyman and critic one year younger than Shakespeare. To a modern sensibility Wits Treasury is a quirky mix of religious instruction, essays on morality, and literary criticism. It was presented as the second in a series of four similar books under the umbrella of “Wit’s Commonwealth.” In his chapter “A comparatiue discourse of our English Poets, with the Greeke, Latine, and Italian Poets,” Meres rates the best of the authors of his time by placing them alongside ancient writers of similar merits. He’s nuts about Shakespeare: “…the sweet, witty soul of Ovid lives in mellifluous & honey-tongued Shakespeare, witness his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugared sonnets among his private friends, &c.” In addition to comparing him to the much-loved Roman poet Ovid here, Meres compares Shakespeare to honey twice in one sentence. “Mellifluous” is derived from the Latin meaning “honey flowing.” Meres goes on to rave that Shakespeare’s comedies are the equal of those by the Roman playwright Plautus and his tragedies are the equal of the Roman playwright Seneca’s, which is to say, Shakespeare is the best at everything.

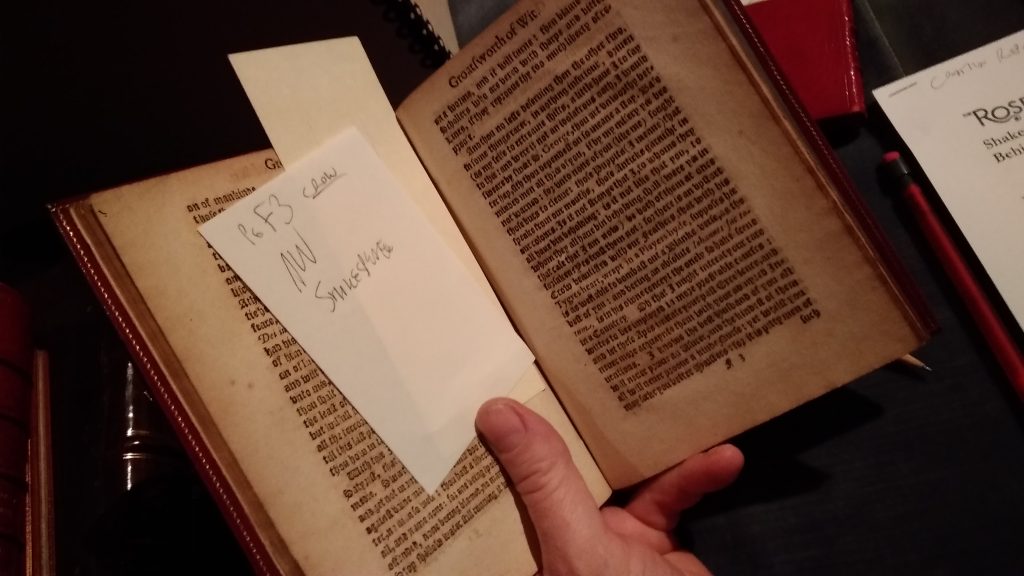

This brings us to the second of these two early Shakespeare reviews at The Rosenbach, an epic takedown visited upon Shakespeare by rival playwright Robert Greene:

Greene was a successful playwright and a prolific writer, six years Shakespeare’s senior, with a University education and a gigantic self-mythologizing personality. Greene did not like Shakespeare. His 1592 deathbed work, Greene’s Groats-worth of Witte, Bought with a Million of Repentance, reads like a brisk novella the length of an Animal Farm or a Breakfast at Tiffany’s. In the context of Greene’s time it would be called a “prose romance.” The most apt modern comparison for Greene’s Groats-worth may be a Simpsons, Family Guy, or South Park episode, a self-consciously knowing narrative that takes shots at contemporaries as it works out its brief plot. Greene’s Groats-worth’s most famous shot hits Shakespeare, as Greene warns his fellow playwrights to beware:

…an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Iohannes factotum [Jack of all Trades], is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrey.

“Shake-scene” is the obvious giveaway of the target of this read, the other being “Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde,” helpfully printed in an alternate font, as you see above. In Henry VI, Part 3, an early history play published in quarto a year before Greene’s Groats-worth, Shakespeare has Richard Plantagenet, the champion of the house of York, call Queen Margaret of Anjou, often speculated to be an inspiration for Game of Thrones’ Cersei Lannister, a “tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide.” Greene recycles this insult for Shakespeare, exchanging “player” for “woman” as a further insult: an actor was less likely to be university educated and thus less worthy of being a playwright than, say, Robert Greene. Shakespeare was criticized for lacking a college education from the beginning of his career to the end of his life and beyond. In his memorial poem in the 1623 Folio, Shakespeare’s frenemy, playwright Ben Jonson, can’t help but remind us that the “Sweet Swan of Avon” had “hadst small Latin and less Greek.”

Whether we love Shakespeare or hate him, it’s satisfying to know that his work and his identity inspired a variety of responses in his lifetime. Are you a Meres or a Greene? Do you regard Shakespeare as an ever-flowing fountain of honey, or (to remix Greene’s metaphor) an upstart crow with a tiger’s heart? We are all entitled to our opinions of Shakespeare, regardless of what florid metaphors we wrap them in. I look forward to the day when we can celebrate Shakespeare’s birthday together again, and the Mereses and Greenes among us can debate in person once more!

Never a word wasted, Andrew. Now I know who you learned it from!