This blog post was written by Andrew White

Sitting by the front and back door of the Rosenbach brothers’ Delancey Place home, these boots dreaded rainy days on which they suffered the discomfort of being used as umbrella stands. Phillip and A.S.W. Rosenbach—our museum’s founders—lived on Delancey Place from 1926 till their deaths in the early 1950s. The one solace for the boots during those years may have been their association with Oliver Cromwell—the farmer and minor landowner who dethroned the Stuart dynasty and ruled England for most of the 1650s. That the boots had been Cromwell’s was more likely a figment of Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach’s fecund imagination than historical fact. All we know for sure is that the boots were meant for riding, hail from the collection of the Rt. Honorable Lord Bateman of Herefordshire, and were purchased from sculptor J. Rochelle Thomas in 1930.

Sitting by the front and back door of the Rosenbach brothers’ Delancey Place home, these boots dreaded rainy days on which they suffered the discomfort of being used as umbrella stands. Phillip and A.S.W. Rosenbach—our museum’s founders—lived on Delancey Place from 1926 till their deaths in the early 1950s. The one solace for the boots during those years may have been their association with Oliver Cromwell—the farmer and minor landowner who dethroned the Stuart dynasty and ruled England for most of the 1650s. That the boots had been Cromwell’s was more likely a figment of Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach’s fecund imagination than historical fact. All we know for sure is that the boots were meant for riding, hail from the collection of the Rt. Honorable Lord Bateman of Herefordshire, and were purchased from sculptor J. Rochelle Thomas in 1930.

When I think of Rosenbach collections, English literature, American literature, and American history spring to mind first, followed by a fine collection of illustrators, some early American portraits, and the largest collection of oil-on-metal portrait miniatures in the United States. But as many of us are stomping back to old stomping grounds and haunting old haunts, my thoughts turn to the Rosenbach’s unjustly lesser-known footwear collection. On my recent post-quarantine return to my favorite Philadelphia restaurant, I contentedly wore blue high-top P.F. Flyers, but did think of the fanciful footwear in the Rosenbach collection and imagined what fun it might be to take them out for an airing—even if only virtually.

In addition to 17th century riding boots, shoes in the Rosenbach collection I imagine would suit my feet perfectly include these that belonged to Mercedes de Acosta, the early 20th century poet and playwright best remembered most for her conquest of some of her era’s most intoxicatingly glamourous women. These sleek black velvet shoes belonged to her:

Dating from the 1910s and made of silk, leather, and rhinestones, these shoes were fashioned by the legendary shoemaker Pietro Yantorny (1874-1936). Yantorny, in addition to being a shoemaker, was curator of the Cluny Museum, France’s National Museum of the Middle Ages and home of the legendary unicorn tapestries. Yantorny proudly called himself “the most expensive shoemaker in the world,” and was also likely the slowest, as orders took him three years to fulfil. These fine shoes will be stepping out for the first in-person Behind-the-Bookcase program we’ve offered in more than a year, Queer Art and Artists on July 15th.

Much as the Rosenbach’s 17th century riding boots were misattributed to Oliver Cromwell’s cobbler, these shoes—simultaneously demure and formidable—were once believed to have belonged to Mercedes de Acosta’s older sister Rita. Rita de Acosta Lyddig was an often-painted, often-photographed, and even sculpted beauty remembered for shocking the world by wearing the first backless dress ever seen at the opera. Her exquisite wardrobe was donated by younger sister Mercedes to the Metropolitan Museum of Art on her death. Rita de Acosta Lyddig owned three hundred pairs of shoes, each of which had its own handmade shoe forms, which Mercedes poetically claimed were made from the wood of old violins! More lovely Yantorny shoes can be seen here on the Met Museum site, but only one other pair, also Mercedes’s, resides at the Rosenbach:

Though not a world-renowned fashion icon like her sister Rita, Mercedes de Acosta was also known for her distinctive style, favoring black and white ensembles, often wearing her hair slicked back, and highlighting her natural pallor with white make-up. Friends and girlfriends nicknamed her “the White Prince,” or “Madame Dracula.” I wonder if Mercedes de Acosta’s signature look was on Dodie Smith’s mind as she created the great villain of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, the monochromatic fashionista Cruella de Vil.

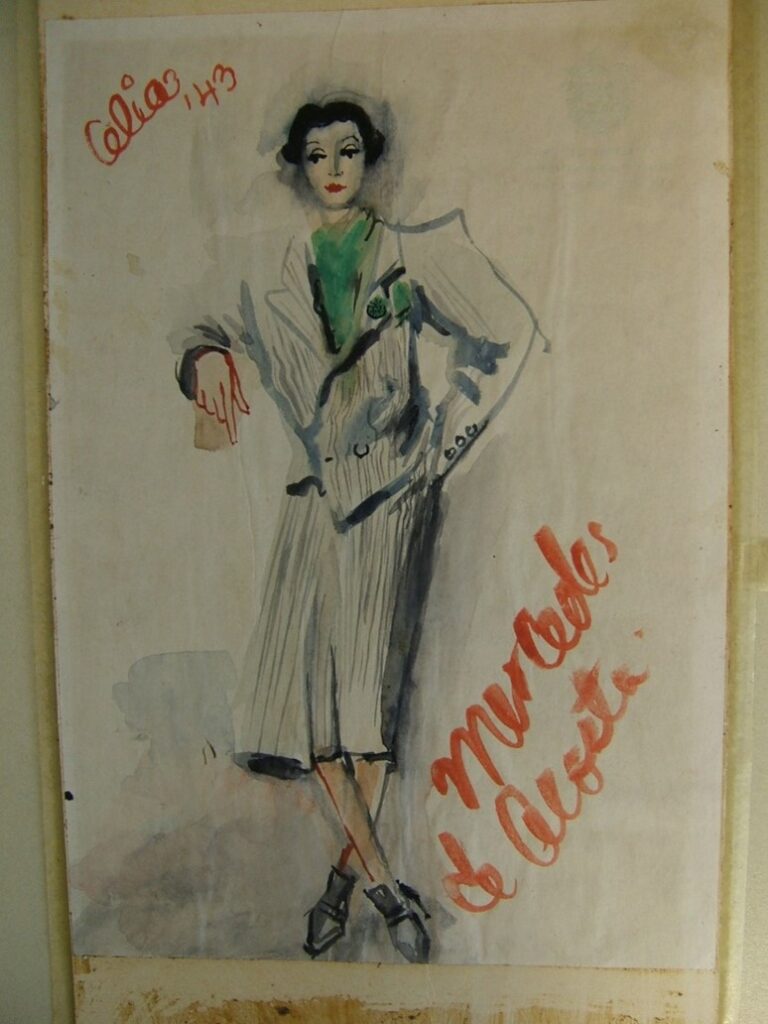

Here’s a watercolor of Acosta from 1943, wearing what look like the black Yantornys above. Realistically, they are probably only slightly more comfortable than the supposed Cromwell boots, so for that reason, among others, I will not be trying them on any time soon. Along with Acosta’s star-studded letters, these shoes were purchased by the Rosenbach in 1959.

Speaking of Mercedes de Acosta, the owner of these silk slippers was her friend, ballerina Tamara Karsavina. The slippers came to the Rosenbach with Acosta’s papers. In 1927, when the exquisitely elfin stage actor Eva Le Gallienne broke up with Acosta, Karsavina wrote her: “I cannot bear to think of you lonely and unhappy… I can hardly believe Eva left you… It seems so cruel… It haunts me…” Late in life, when Acosta was down on her luck, Karsavina sent her money and invited her to come stay with her in London. Acosta’s rainbow of magnificent lovers tends to upstage other aspects of her life, but in addition to being a playwright and cassanova, she inspired loyal friendship in many.

Another writer with the gift of friendship was poet Marianne Moore, who will close this look at the Rosenbach’s little-known shoe collection. Moore’s archive and personal effects came to the Rosenbach on her death in 1972, bringing correspondence from T.S. Elliot, Langston Hughes, Elizabeth Bishop, and Harry Belafonte, among many other cultural riches, not least, this masterful Modernist’s manuscripts.

And shoes. These snowshoes are from Moore’s collection:

But alas, they are too small to be of any practical use in our Philadelphia winters.

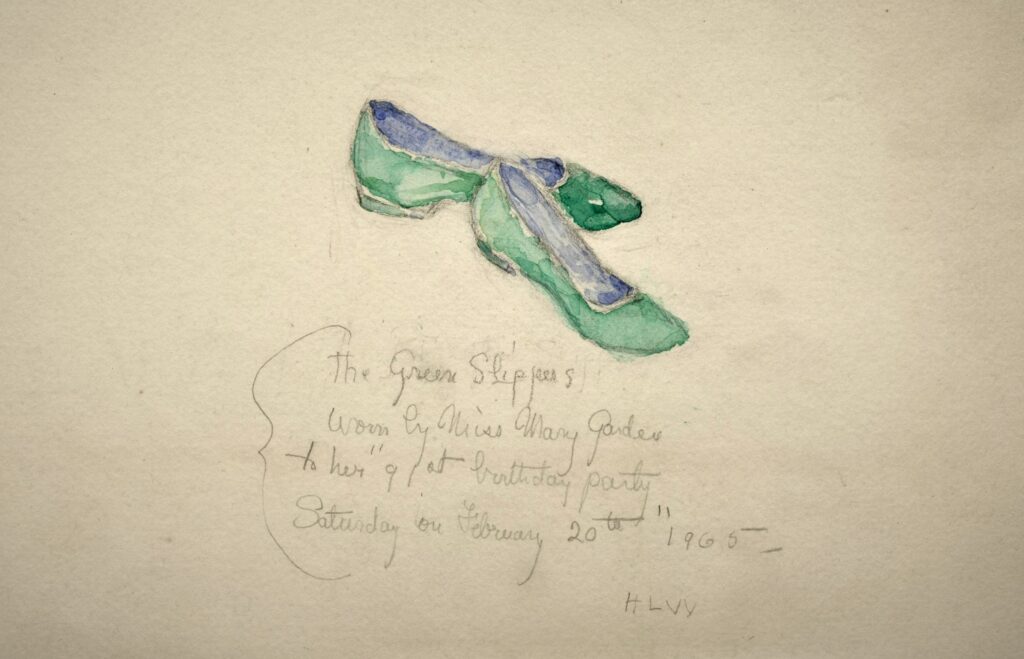

Also from Marianne Moore is this charming watercolor, precisely labeled “The Green Slippers worn by Miss Mary Garden to her 91st birthday party, Saturday February 20th, 1965.” The artist is Moore’s friend Hildegarde Watson, who, by pure coincidence, also favored wearing black and white like Mercedes de Acosta. Watson was an actress, concert singer, and patron of the arts. In her early years she starred in two expressionistic short films, The Fall of the House of Usher (1928), and Lot in Sodom (1933). My best guess for the owner of the viridescent footwear she painted is the opera singer Mary Garden, who was born February 20, 1874 and would have been 91 in 1965. Garden created the role of Melisandre in Debussy’s only opera, Pelleas and Melisandre, but said her most popular role was the titular courtesan in Massenet’s Thais, “because I wore least.” As we, the fortunate vaccinated of Philadelphia, return to old haunts and explore new ones, let’s think of Miss Mary Garden, stepping out in the hopeful color of new growth in her 91st year.

Some shoes know how to tell a good story and so do you, Andrew. This deep dive into the treasure chests reminds me of a surprisingly wonderful visit at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto. Thanks for highlighting such interesting aspects of the Rosenbach collections