Today marks the 195th anniversary of the sinking of the whaleship Essex, which was famously “stove by a whale” on November 20, 1820. I’m a bit of a maritime history junkie, so I’ve made reference to the story before, but with a major movie about the wreck opening in December, it seemed that it could merit a post of its own.

The basic story of the Essex (which has been recounted in Nathaniel Philbrick’s excellent In the Heart of the Sea, as well as many, many, other worthy books and articles) is as follows. The whaleship Essex, sailing under first-time captain George Pollard, left Nantucket on August 12, 1819. It had a mixed crew of Nantucketers and mainlanders and included a number of African-American sailors (Philbrick’s book delves deeply into the dynamics of this mix). After getting knocked down in a storm only two days out, they proceeded around Cape Horn to the west coast of South America and then to the offshore whaling grounds, far from the coast, which had just been discovered in 1818.

On November 20, 1820, the ship was at 0° 40′ south latitude, 119° 0′ west longitude. Whales were sighted and most of the crew took to the ship’s three whaleboats in pursuit. One of the small boats was damaged by a whale that it had harpooned (a common occurrence) and so it returned to the Essex for repairs. As the first mate, Owen Chase, hammered canvas onto the damaged boat, a very large sperm whale was spotted near the ship. Here’s how Chase described what happened next:

… he came down upon us with full speed, and struck the ship with his head, just forward of the fore-chains; he gave us such an appalling and tremendous jar, as nearly threw us all on our faces. The ship brought up as suddenly and violently as if she had struck a rock, and trembled for a few seconds like a leaf. We looked at each other with perfect amazement, deprived almost of the power of speech….

I perceived the head of the ship to be gradually settling down in the water; I then ordered the signal to be set for the other boats, which, scarcely had I despatched, before I again discovered the whale, apparently in convulsions, on the top of the water, about one hundred rods to leeward. He was enveloped in the foam of the sea, that his continual and violent thrashing about in the water had created around him, and I could distinctly see him smite his jaws together, as if distracted with rage and fury. He remained a short time in this situation, and then started off with great velocity, across the bows of the ship, to windward. By this time the ship had settled down a considerable distance in the water, and I gave her up for lost….

I was aroused with the cry of a man at the hatch-way, “here he is – he is making for us again.” I turned around, and saw him about one hundred rods directly ahead of us, coming down apparently with twice his ordinary speed, and to me at that moment, it appeared with tenfold fury and vengeance in his aspect. The surf flew in all directions about him, and his course towards us was marked by a white foam of a rod in width, which he made with the continual violent thrashing of his tail; his head was about half out of water, and in that way he came upon, and again struck the ship…He struck her to windward, directly under the cathead, and completely stove in her bows. He passed under the ship again, went off to leeward, and we saw no more of him.

The twenty men of the Essex had some time to gather supplies from the doomed ship into the three whaleboats, but they soon had to face the fact that they were stranded in small boats in a remote part of the Pacific Ocean. The closest inhabited lands were the Marquesas and Society Islands, about 1500 miles to the west, but rumors of cannibalism there led them to steer for South America, which was about 2000 miles away against the prevailing winds and currents.

After a month at sea, the boats landed on deserted Henderson Island. Three men chose to stay there; the remaining seventeen pressed on. The boats eventually got separated; one was lost but the other two were rescued after 90 and 95 days at sea. The five survivors in those boats had been forced to rely on cannibalism, in one case actually drawing lots and killing a man for food. The three men on Henderson were also alive, barely, when a rescue party manged to reach them, bringing the total number of survivors to eight.

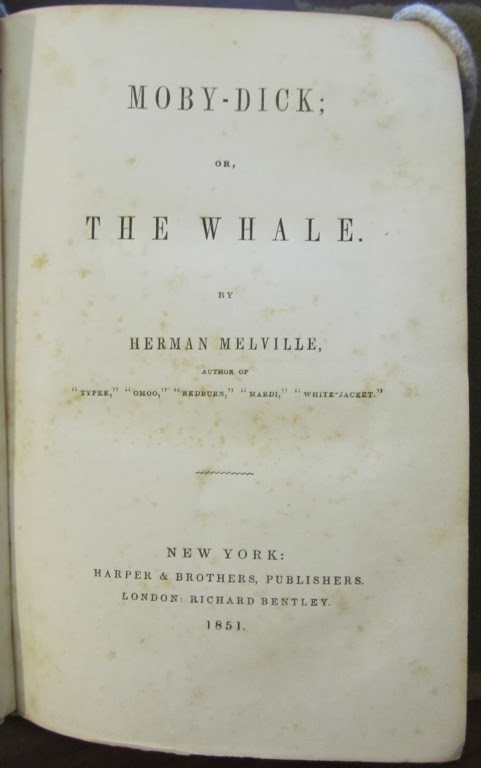

If the idea of a ship being sunk by a whale sounds familiar, that is not coincidental. The story of the Essex was quite famous in the 19th century and Herman Melville knew it well. In 1821, Owen Chase, the Essex’s first mate, published a Narrative of the most extraordinary and distressing shipwreck of the whale-ship Essex (it was probably ghost-written based on his account of events). Harvard’s Houghton Library preserves (and has digitized!!) Melville’s own copy of the Narrative. This copy was a gift from his father-in-law in 1851, but on the blank pages in the front Melville explains that had read the Narrative long before:

When I was on board the ship Acushnet of Fairhaven, on the passage to the Pacific cruising grounds, among other matters of forecastle conversation at times was the story of the Essex. It was then that I first became acquainted with her history and her truly astounding fate…

We spoke another Nantucket ship and gammed with her. In the forecastle I made the acquaintance of a fine lad of sixteen or thereabouts, a son of Owen Chase. I questioned him concerning his father’s adventure; and when I left his ship to return again the next morning (for the two vessels were to sail in company for a few days) he went to his chest and handed me a complete copy (same edition as this one) of the Narrative. This was the first printed account of it I had ever seen & the only copy of Chace’s narrative (regular & authentic) except the present one. The reading of this wondrous story upon the landless sea, & close to the very latitude of the very latitude of the shipwreck had a surprising effect upon me.

Melville also mentions having read an extract from an account purportedly written by Captain Pollard, but he had “not seen the work itself.” In 1852 he would actually meet Pollard on Nantucket, and added a note about that in green pencil. (The cabin boy Thomas Nickerson also wrote an account,which remained lost and unpublished until the 1980s.) Some of the Essex connections Meville describes on the pages of his Narrative seem a bit confused (he claims to have seen Owen Chase on a whaling ship, which was impossible as Chase was retired by then, and he remembers that an Acushnet officer had served under Chase, but seems to have have mixed up which officer), but it is clear that the story of the Essex made a deep impression on him during his time at sea.

In Chapter 45 of Moby Dick, Melville specifically describes the story of the Essex (and his meeting with Chase’s son) and quotes from Chase’s Narrative as proof that “The Sperm Whale is in some cases sufficiently powerful, knowing, and judiciously malicious, as with direct aforethought to stave in, utterly destroy, and sink a large ship; and what is more, the Sperm Whale has done it.”

Then of course there is the sinking of the Pequod itself in Chapter 135:

From the ship’s bows, nearly all the seamen now hung inactive; hammers, bits of plank, lances, and harpoons, mechanically retained in their hands, just as they had darted from their various employments; all their enchanted eyes intent upon the whale, which from side to side strangely vibrating his predestinating head, sent a broad band of overspreading semicircular foam before him as he rushed. Retribution, swift vengeance, eternal malice were in his whole aspect, and spite of all that mortal man could do, the solid white buttress of his forehead smote the ship’s starboard bow, till men and timbers reeled. Some fell flat upon their faces. Like dislodged trucks, the heads of the harpooneers aloft shook on their bull-like necks. Through the breach, they heard the waters pour, as mountain torrents down a flume.

The disbelieving response of the men in the Pequod’s whaleboat “”The ship? Great God, where is the ship?” echoes Chase’s Narrative, in which a boat-steerer cries out aghast “O, my God, where is the ship!”

So with this very short recap of the Essex and Moby Dick you are all set to check out the movie version of In The Heart of the Sea, directed by Ron Howard, which comes out on December 11. It’s only rated PG-13, so I imagine that there has to be a lot that happens off camera. I guess we’ll see.