Since Frankenstein & Dracula: Gothic Monsters, Modern Science opened on Friday the 13th of October, I’ve fielded a few questions from surprised visitors: Dracula, really? It’s not difficult to see the connection between Frankenstein and the scientific theme of our new exhibition, but many readers are surprised to see us categorize Dracula as another gothic novel preoccupied with science. We tend to focus on the elements that made it such an iconic work of gothic horror: Stoker’s vision of the dangerous vampire preys on fear of the dark, bodily hungers, and endangered maidens.

But Bram Stoker was fascinated by the science of his day—particularly medical science. His older brother, Thornley, was a notable surgeon; some of Thornley’s lectures on brain surgery appear in Bram Stoker’s notes for Dracula. In the novel, when the lovely Lucy Westenra falls ill after a sleepwalking episode, mental asylum doctor John Seward and the famous Professor Abraham Van Helsing attempt to pinpoint the medical cause of her neck wound and bloodlessness by process of elimination, like a nineteenth-century episode of CSI.

In the late nineteenth century, medical science included some exploratory fields that we might not strictly consider science today. For example, Bram Stoker was a member of the Society for Psychical Research, a group of spiritualists whose supernatural and psychic investigations were taken seriously by at least some of their members (notably including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of mastermind Sherlock Holmes and believer in fairies). Here are just a few of the scientific theories and practices manifested in Dracula that may not quite hold up in the present day, but that must have seemed as potentially profitable and potentially dangerous as cutting-edge twenty-first century technologies do to us. In the context of this gothic horror classic, science and medicine play a vital role in ramping up the suspense, creepiness, and dread.

Blood Transfusions

After her sleepwalking episode carries her to a midnight encounter with Dracula himself, Lucy is found in her bed exsanguinated almost to the point of death. To revive her, the Van Helsing proposes replenishing her blood with his own, as well as donations from Lucy’s fiance and her jilted lover, the asylum doctor John Sewell. This novel predates blood typing, so there is no mention whether the blood of her rescuers will be compatible with Lucy’s; it is presumed that their male vitality will liven her up.

At the same time, the potentially life-saving practice of blood transfusion bears uncertain and uneasy implications for these characters. The vampire hunters consider it somewhat improper to inject Lucy with the vital fluids of so many men at once; doting fiancé Arthur Holmwood is so ecstatic about sacrificing his strength for Lucy’s health that Van Helsing and John Sewell quietly agree not to tell him that they donated blood to her as well. Then, of course, there is the uncomfortable parallel between the doctors transfusing blood into the unconscious Lucy and the villainous Count himself forcing blood onto the unwilling Mina Harker later in the novel.

Physiognomy

The belief that physical features can be interpreted to reveal personality is an ancient idea, but the practice of physiognomy was still alive and well in Stoker’s day. In the late nineteenth century, in connection with the rise of criminal investigation and violent conflicts over human slavery, physiognomic theory was used to support criminal profiling and justify racial discrimination: proponents pointed to the size of the forehead, the shape of the nose, or the set of the eyes to make broad generalizations about intelligence and tendency toward criminal behavior in disadvantaged populations.

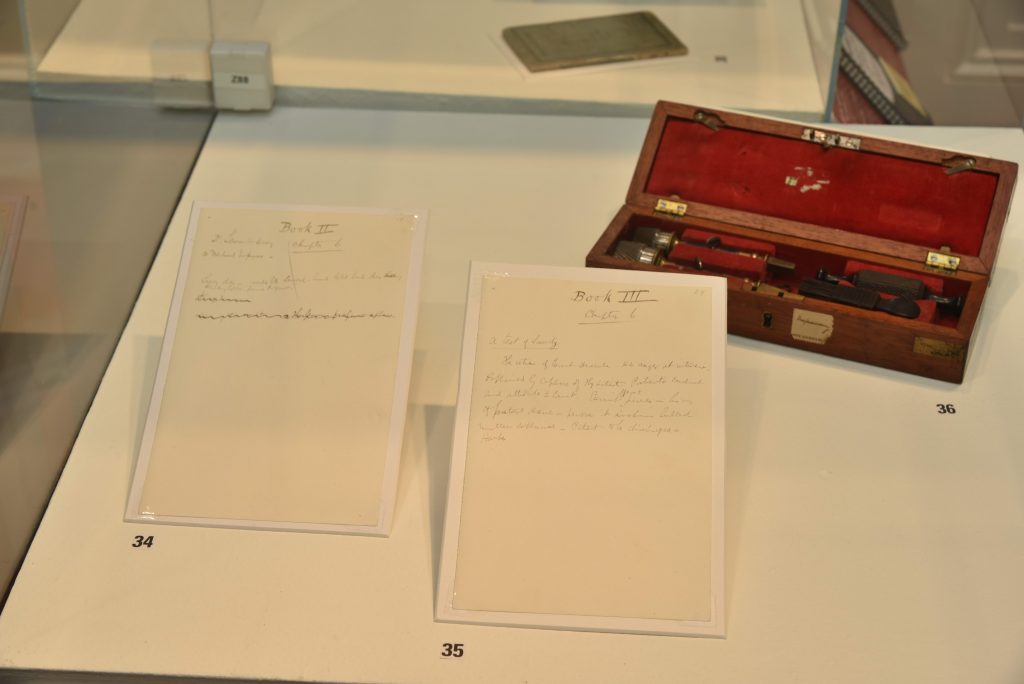

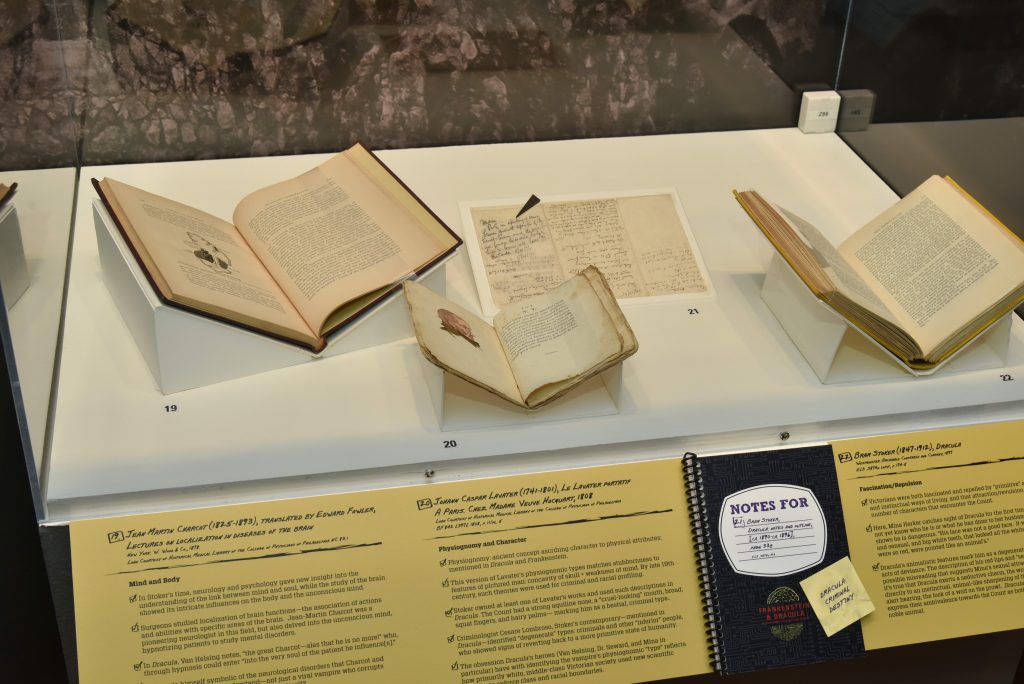

On display in our exhibition is an 1808 book of physiognomic types by Swiss philosopher Johann Caspar Lavater, on loan from the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia; the book (pictured below center) is illustrated with different physiognomic types which are accompanied by an explanation of associated personality traits. Stoker owned one of Lavater’s books and almost certainly drew from physiognomy to construct the villainous vampire we know and love: Dracula’s iconic aquiline nose and “cruel” red mouth were intended to be outward indicators of his evil nature (along with hairy palms and stubby fingers, which we don’t see as often in cinematic portrayals).

Hypnotism

Like physiognomy, hypnotism is an ancient practice that was finding new life and surprising applications in Stoker’s era. In the early nineteenth century, methods of lulling patients into a trance state or “nervous sleep” were found to make them more susceptible to suggestion. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, when Stoker was planning Dracula, theorists such as Sigmund Freud introduced principles of psychoanalysis into the field, conjecturing that the altered state of consciousness induced by hypnosis might reveal layers of the patient’s unconscious mind and repressed memory. Stoker goes a step further and reimagines hypnotism as a means to amplify psychic links.

Possibly literature’s first female vampire hunter, the loyal and courageous Mina Harker finds herself telepathically connected to Dracula after he attacks her. She asks Professor Van Helsing to hypnotize her, and he lulls her into a quiet state similar to sleep and begins to ask her about her surroundings. Mina’s responses indicate that, unfettered by conscious thought, she can perceive what Dracula perceives. Her husband, Jonathan Harker, records the interview in his journal:

“What do you see?”

“I can see nothing; it is all dark.”

“What do you hear?” I could detect the strain in the Professor’s patient voice.

“The lapping of water. It is gurgling by, and little waves leap. I can hear them on the outside.”

“Then you are on a ship?” We all looked at each other, trying to glean something each from the other. We were afraid to think. The answer came quick:—

“Oh, yes!”

“What else do you hear?”

“The sound of men stamping overhead as they run about. There is the creaking of a chain, and the loud tinkle as the check of the capstan falls into the rachet.”

“What are you doing?”

“I am still—oh, so still. It is like death!” The voice faded away into a deep breath as of one sleeping, and the open eyes closed again.

There are many more examples of science—both fiction and fact—in Dracula: sleepwalking, viruses, theories of degeneration. You can explore them in our exhibition, or check out any of our upcoming programs dedicated to Bram Stoker and his literary legend.