This blog post was written by Andrew White

With a beautiful Vale Press book (Wilde’s House of Pomegranates) on display in the Rosenbach’s current Of Two Minds exhibit, William Morris has been on my mind; Morris’s renowned Kelmscott Press was a significant influence on Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon when they created Vale Press. This week I took a look at one of the objects in the Rosenbach collection that was created by this unique rebel Victorian (1834-1896): the first book printed by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, The Story of the Glittering Plain. William Morris put his stamp on textile and wallpaper design, was an influential leader in Britain’s socialist movement, learned Icelandic and translated the sagas, wrote poetry and literary fantasy, presumably never slept, and, as his final achievement, is credited with designing and printing some of the loveliest books ever made. Here’s Morris’s enchanting Kelmscott Press colophon:

As his colophon intimates, everything Morris produced turned out lovely, gracious, and charming (except his one foray into painting, which Morris himself admitted was a disaster). Morris said of Kelmscott that he “began printing books with the hope of producing some which would have a definite claim to beauty…” and indeed, Kelmscott volumes are ranked among the most beautiful ever made. Much as he did with the production of the textiles, furniture, and tiles made by Morris & Co., Morris looked to preindustrial methods to produce Kelmscott books. Each is made with hand sewn bindings and handmade linen paper, and each is designed within the neo-Medieval idiom that made all Morris’s creations look like lost relics of a psychedelic Camelot.

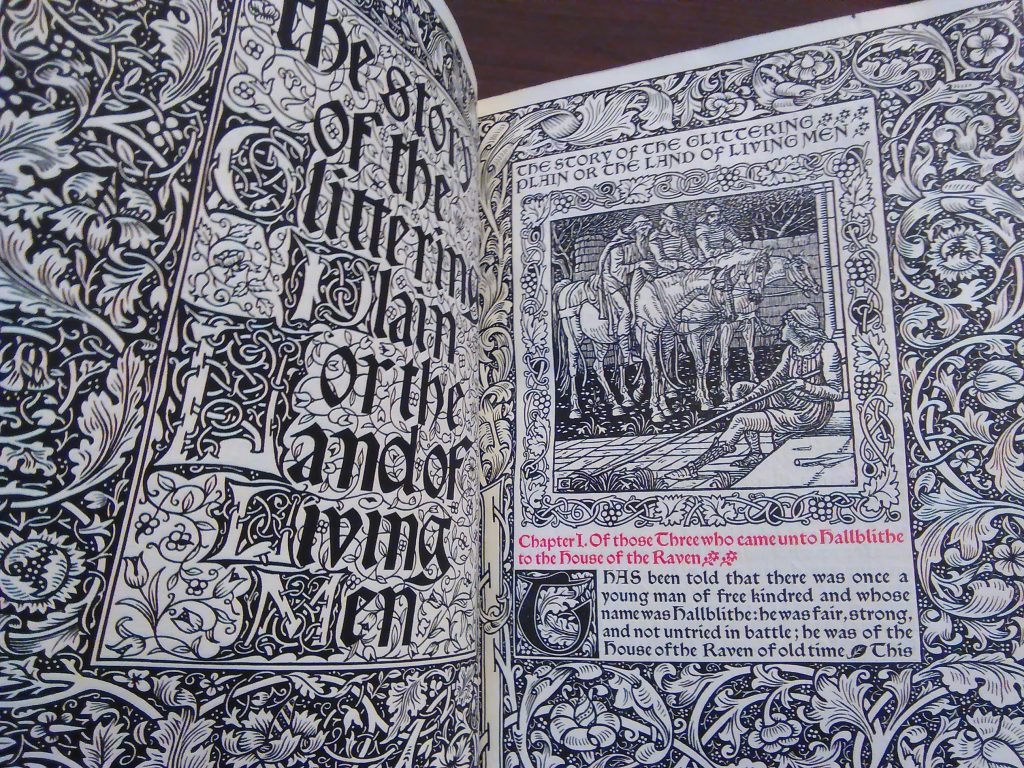

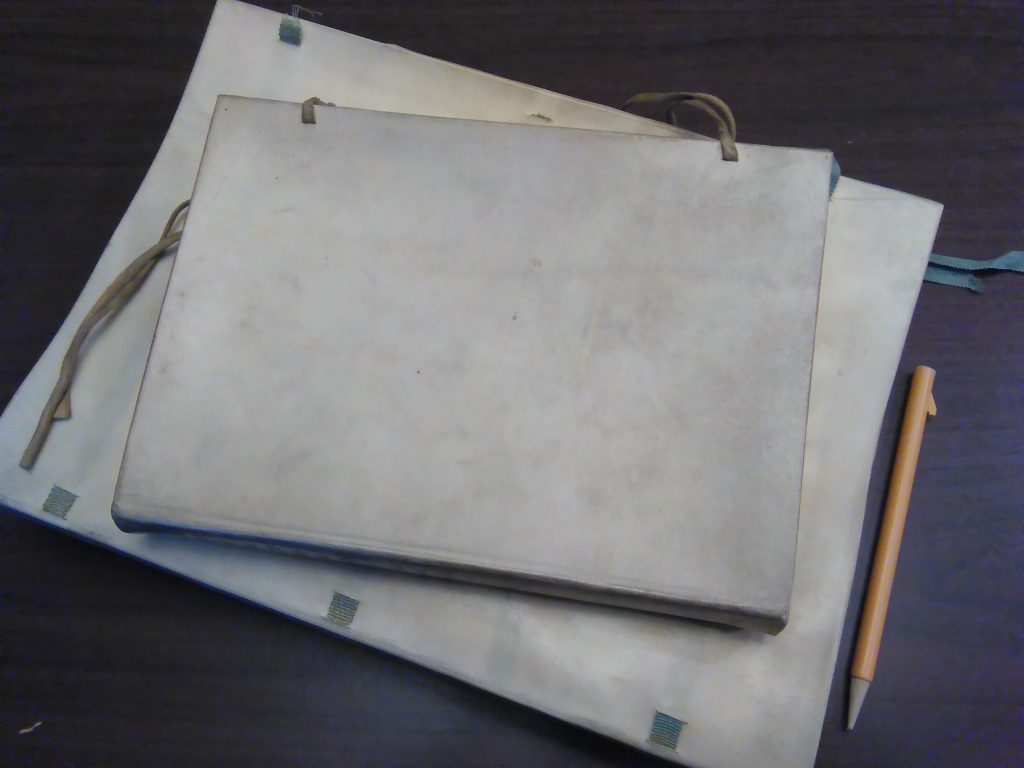

As a lifelong fan of Morris’s work in textiles, tapestries, and stained glass, and an admirer of his progressive politics, I am late in coming to his fiction—but this week finally found my way into Morris’s fictional universe by reading the first novel to be printed by his press, his own Story of the Glittering Plain. One year before its Kelmscott debut in 1891, Glittering Plain appeared in The English Illustrated Magazine, and was then reprinted by Kelmscott in 1894 in a larger format, with a different font, and illustrations by Walter Crane—making it the only book Kelmscott printed twice. The Rosenbach has both the 1891 and the 1894 versions, and here you can see the relative sizes of the two printings:

After reading the first half of Glittering Plain on marxists.org—hoping that would please the great man if he were watching from the People’s Republic of Heaven—I finished Glittering Plain by reading the text of the Rosenbach’s lavish 1894 copy (the larger of the two books in the picture above). As an avowed, Ren Faire-attending fantasy geek and devoted Pre-Raphaelite, it was magical to read a William Morris novel printed by William Morris’s own press. Here is my take on The Story of the Glittering Plain:

I’d heard about the deeply hobbitty nature of Morris’s tales—Tolkein admitted a debt to him—and Glittering Plain did not disappoint on this score. Weapons are “dwarf-wrought” and characters break into Tom Bombadil-like singing at the least provocation. Our story begins in Cleveland—not the Cleveland you’re thinking of—but Cleveland-by-the-Sea, the former county of Cleveland along England’s east coast. As is fitting for a fable by an ardent socialist, Cleveland-by-the-Sea is a classless society. When three strangers seeking the titular Glittering Plain ask the story’s hero—Hallblithe of the House of the Raven (“fair, strong, and not untried in battle”)—to lead them to his king, Hallblithe winningly replies, “…I know not this word, for here dwell we, the sons of the Raven, in good fellowship…” Fantasy’s congenital weakness for royalist tropes makes Cleveland-by-the-Sea’s democratic governance a rarity in the genre.

Morris gives his hero Hallblithe an appealing sidekick and a pallid love-interest. The latter—and the catalyst for Glittering Plain’s plot—is “an exceeding fair damsel called the Hostage, who was of the House of the Rose.” The Hostage—the only name this character ever receives—serves as diplomatic collateral between the House of the Raven and her own neighboring House of the Rose. The Hostage’s lack of a proper name was one of the disappointments of The Story of the Glittering Plain, though a heroine with backstory and a personality is always appreciated by this reader as well. When the Hostage is kidnapped for real—by villains reminiscent of Barbary Pirates, from the fittingly-named “Isle of Ransom”—Hallblithe goes on a journey to find her and meets a trickster/sidekick character with the terrific name of Puny Fox. (Puny Fox is puny only in comparison with his gigantic family). For me, the unanswered question that looms above The Story of the Glittering Plain is why Hallblithe persists in his quest for the bland “Hostage” after the bearded ginger Puny Fox enters the tale with humor, panache, and an almost flirtatious way of alternately helping and bewildering him.

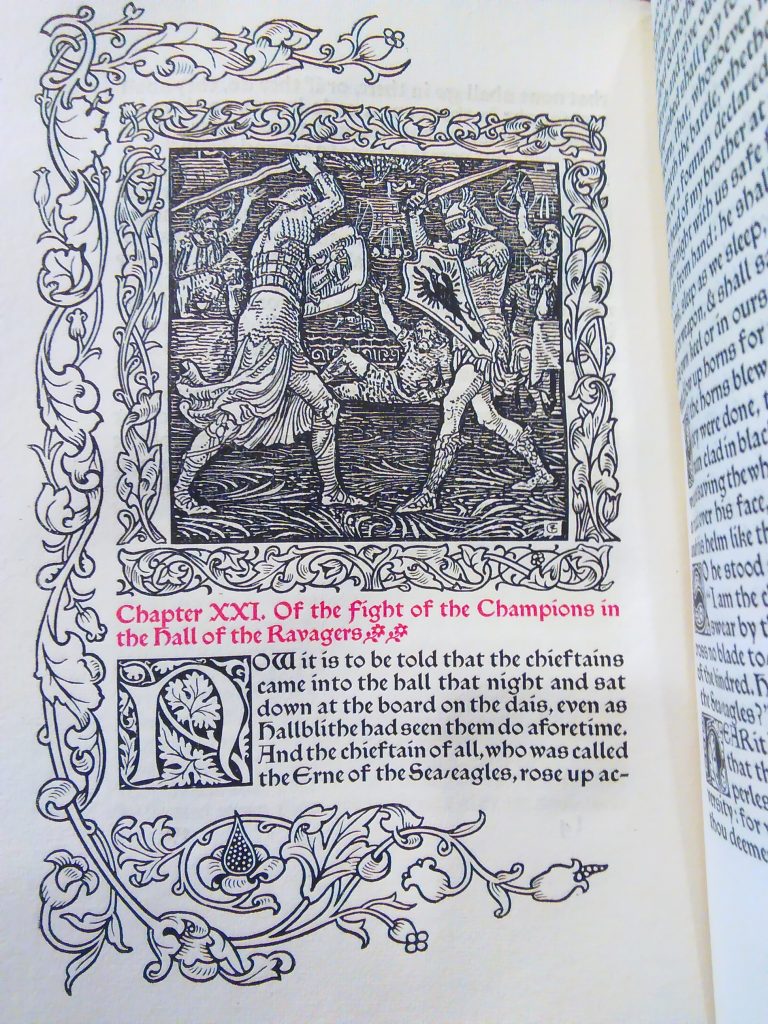

Above is Walter Crane’s illustration of the Puny Fox and Hallblithe in a mock battle the Fox instigates to save Hallblithe from a real duel, which Hallblithe, when undeceived, objects to from some casuistic delusion of honor, thereby endangering both his and the Fox’s life. At this, the Fox grouses: “Well now, brother-in-arms, I have been trying to learn thee the lore of lies, and surely thou art the worst scholar who was ever smitten by master.” Why is the clever, good-natured Puny Fox not the hero of this book? The Fox begins the story as an irascible, nearly-dead old man, finds renewed youth in the utopian Land of the Glittering Plain, and forsakes immortality for the pleasures of friendship and mortal life, while all Hallblithe does is doggedly and humorlessly seek his beloved “Hostage.” I think we can all see who has the more satisfying dramatic arc here; Puny Fox is an Odysseus robbed of his Odyssey.

Glittering Plain proved an anti-climactic start to my long-delayed reckoning with William Morris’s fiction, but reading a Morris story in a book printed by Morris himself was a good way to commune with one of my heroes—and could only have been better if I had done it at Kelmscott Manor with Morris himself looking over my shoulder to remind me that bewray means abuse and carle means man and to sing his own songs for me in a hearty, Bombadil-like voice. If you would like to have a look through a Kelmscott book for yourself, the Kelmscott Poems of William Shakespeare is one of the books featured on the Rosenbach’s Shakespeare Hands-on Tour, next offered on April 20.

Thank you for the wonderful article

Beautiful! A wonderful design and production. Nice to get a chance to see it up close. Thanks!

Is “People’s Republic of Heaven” your phrase? I love it.

Do they explain why it’s called Glittering Pain? Its’ such a modern term–like the title of a New Yorker story.