The summer of 2020 was undoubtedly unlike any other. While we still saw warm temperatures and fair weather, many of us spent the season indoors and away from others due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite these peculiar circumstances, many found the opportunity to challenge themselves creatively while stuck inside. The end of the summer also marks the birthday of Mary Shelley– an author who also knew the creative potential that could be born from being confined indoors. Born on August 30th, 1797, Mary Shelley is best known for her novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, a transformative piece for both the horror and science fiction genres. Frankenstein grapples with themes of loss and finding one’s own purpose in life, all amplifying the novel’s dark tone. It comes as no surprise then that Mary’s own life was marred by tragedy and struggle. After losing her mother, famed feminist author Mary Wollstonecraft, shortly after her birth, Mary was raised by her father, William Godwin. Godwin was a political philosopher who cared for Mary’s education, but was also deeply in debt.

In her teenage years, Mary became acquainted with the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the two began a romantic relationship. Unfortunately for the young couple, Mary’s father disapproved of their courtship, forcing the two to meet only in secret, usually at Mary’s mother’s grave. In 1814, the couple finally eloped to France and Mary soon became pregnant. The Shelleys were penniless, far from home, and Mary was often ill during her pregnancy. The child was born two month premature, and passed away not long after birth. Mary was devastated by the loss of her child, writing in a letter to her close friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg:

My dearest Hogg my baby is dead—will you come to see me as soon as you can. I wish to see you—It was perfectly well when I went to bed—I awoke in the night to give it suck it appeared to be sleeping so quietly that I would not awake it. It was dead then, but we did not find that out till morning—from its appearance it evidently died of convulsions—Will you come—you are so calm a creature & Shelley is afraid of a fever from the milk—for I am no longer a mother now.

By 1816, though, Mary and Percy had conceived again, and Mary gave birth to their first son, William, which helped to raise her spirits. In that same year, the Shelleys met Lord Byron, a fellow English poet, who invited them to summer with him in Switzerland, where he had rented a countryside mansion named Villa Diodati.

The group that convened in Geneva that summer consisted of Lord Byron, his physician John Polidori, the Shelleys, and Clair Clairmont, Mary’s step sister. But unbeknownst to them, the relaxing summer getaway they had planned would take an unexpected turn. Spring had come and gone as normal, but the summer was marred by cold temperatures and overcast skies. In the year prior to the group’s vacation, an active volcano located in Indonesia named Mount Tambora had erupted, killing tens of thousands of locals. The eruption released volcanic ash into the stratosphere, which left the sky with a dusty atmosphere for several years. The effects of the volcanic eruption were devastating–crops failed to grow throughout Europe, North America, and Asia, due to cold temperatures and flooding. As a result, the group found themselves spending most of their time indoors, during what Mary would later recall as a “wet, ungenial summer” in the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

As the unusual weather raged on, the group found themselves spending most of their time indoors, either in their own rentals or with each other in Villa Diodati. To pass the time, they entertained themselves by telling German ghost stories and folk tales around the fireplace. It was during these nights indoors that, according to Mary, Lord Byron suggested the group challenge themselves to write ghost stories of their own. Everyone quickly began work on their stories, except for Mary, who according to her own account, struggled to think of an idea. The group continued the nightly fireside chats, discussing not only ghost stories but also scientific concepts such as galvanism, particularly the idea of reanimating the dead by means of electricity. It was after one of these nightly discussions that Mary had what she described as a “waking dream.” In the 1831 preface of Frankenstein, Mary recounted this dream, stating she saw “the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. …” Finally, days after Lord Byron issued his challenge, Mary had her ghost story.

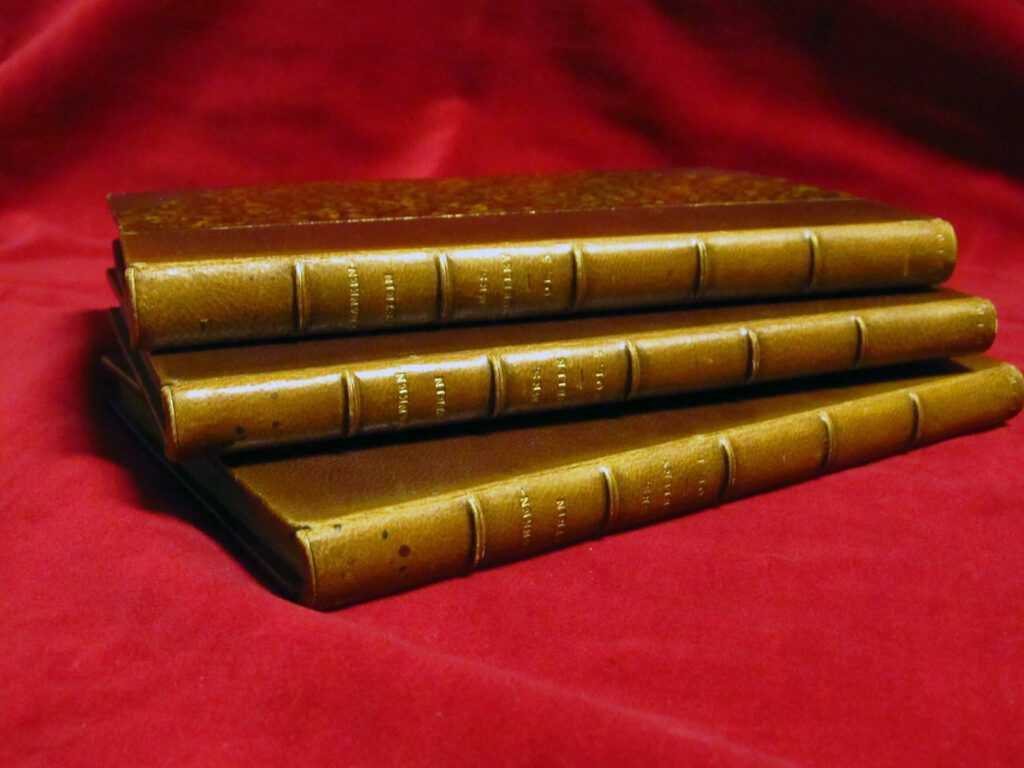

Mary quickly began building upon her idea, originally intending to write a short story. As she continued to write, though, her short story evolved into a more intricate, full length novel. Percy helped to edit Mary’s work, writing the preface as well. When the novel was finally published on January 1, 1818, Mary’s name was omitted. In fact, because Percy wrote the preface, many readers assumed that he was actually the author. The first run of Frankenstein was a small production, with only 500 copies of the novel printed. The novel initially received mixed reviews.Some critics found the plot absurd and unscientific while others took issue with the dedication to radical philosopher William Godwin, Mary’s father. Despite its limited run and unfavorable reviews, Frankenstein was popular amongst readers. Thomas Love Peacock, a close friend of the Shelleys, recalled in a letter to Percy that he was hounded by questions about the novel shortly after its publication, speculating it to be “universally known and read”. Frankenstein received a revised edition in 1831, now with Mary’s name attached. She also wrote the preface for this edition, recalling her fateful summer at Villa Diodati. And now that we all find ourselves in a similar situation, perhaps her birthday is the perfect opportunity to reflect on Mary Shelley’s seminal work Frankenstein and the summer she spent indoors.

Two summers, dark with dread of what lies ahead, yet somehow illuminated by our hopes and humanity. Best wishes for good health!