Greetings from Frozen Philadelphia!

After a snowy weekend and a lot of single-digit temperatures, we’re bundled up and back in the office. And as we shiver on our way to and from the museum, we’re thinking about some of our favorite authors, who shivered during an unseasonably cold summer 202 years ago. During the summer of 1816, Jane Austen yearned to go outside for a walk, but ceaseless rain kept her indoors and revising Persuasion; already in poor health, Austen died the following year and her final novel was published posthumously. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge also complained of “this end of the world weather” preventing him from getting exercise; perhaps that is why his Biographia Literaria expanded from the short preface he intended to a two-volume collection of essays and autobiography. And, of course, we all love the story of Lord Byron’s summer on Lake Geneva, when the poet read Fantasmagoria aloud with his summer houseguests–his admirer Claire Clairmont, his doctor John Polidori, his friend Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Shelley’s paramour Mary Godwin–and challenged them to write their own spooky stories, one of which would become Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

The guests at Byron’s Villa Diodati could not know it, but the cold wet weather that kept them indoors originated from a volcanic explosion one year earlier and half a world away. In April 1815, Mount Tambora erupted with deadly force, killing tens of thousands in Indonesia and sending tons of dust and sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. The resulting particulate and sulfuric acid blocked solar radiation and disrupted weather patterns, causing widespread climate change for several years after the event. 1816 brought months of summer rain to England and an unexpected June snow in Connecticut. Precipitation and low temperatures damaged crop yields worldwide, leading to food scarcity everywhere. While most of the world cooled, a thick blanket of volcanic dust caused the Arctic temperatures to rise, resulting in a loss of sea ice. As storms raged half a world away from the volcano, the monsoon cycle was slowed in southeast Asia; this abnormality allowed a strain of cholera bacterium to mutate and spread, leading to the first of several devastating cholera pandemics in the nineteenth century.

At the time, many of those affected by the weather in England and abroad were not even aware that the eruption had occurred–and if they had known, they likely would not have made the connection.1 Yet even without our modern understanding of weather patterns and volcanic winters, Shelley and her contemporaries were preoccupied by the changing climate and environmental extremes. For example, the “end of the world weather” of storms and rain made a foreboding backdrop for the awakening of Frankenstein’s creature: it is a “dreary night of November,” and “rain pattered dismally against the panes” as Victor Frankenstein toiled into the night (Frankenstein, Chapter 5). The story of his search for knowledge is framed within an unforgiving polar landscape: the novel opens and closes with the narrative of Arctic explorer Captain Waldon, who is by turns fascinated, inspired, and repulsed by Victor’s tale.2 A volcano even makes a metaphorical appearance, evoking the violent agitation of Frankenstein’s mental state at the novel’s close: “Sometimes he commanded his countenance and tones and related the most horrible incidents with a tranquil voice, suppressing every mark of agitation; then, like a volcano bursting forth, his face would suddenly change to an expression of the wildest rage as he shrieked out imprecations on his persecutor” (Frankenstein, Chapter 24).3 Two centuries ago, as the world was beginning to see enormous growth in scientific and industrial progress, perhaps these natural extremes in fiction represented the limits of human knowledge or power. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the irrepressible depth and awesomeness of the natural world are both temptation and warning: Waldon is obsessed by polar exploration just as Frankenstein was obsessed with the alchemy of life, but in their monomaniacal pursuits, they risk putting other human lives in danger.

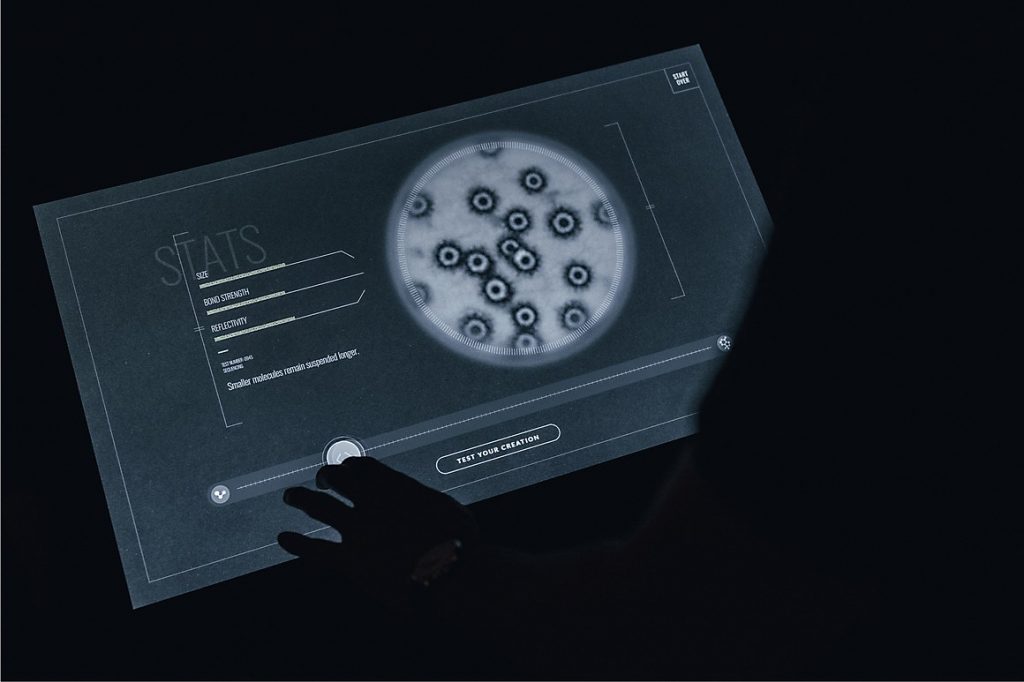

Frankenstein may not exactly be cli-fi (or science fiction about climate change), but both the environmental themes of the novel and the unseasonable summer that inspired it might encourage contemporary readers to reflect on climate change in the present. It’s easy to joke about global warming when the East Coast is being blasted by a “bomb cyclone” of snow, but the Mount Tambora eruption shows that climate change can affect different parts of the globe in different ways–and if one volcano’s particulate can change the world for two years, we would do well to consider the environmental impact of our enormous human population. We make this connection explicit in the Frankenstein & Dracula exhibition: in the digital interactive created by Bluecadet, one of the Modern Monsters you are invited to combat is a warming earth: in an imagined future, global temperature have continued to rise and crops are withering in the sun; you, the scientist, must consider the ethics and effectiveness of injecting a synthetic particulate into the air.

Embedded within a gallery full of manuscripts, novels, and reference books of the past, this modern activity invites you to connect the science fictions, facts, and fears of two centuries ago and those we experience today. But if the cold, wet weather is keeping you indoors, Bluecadet has made the interactive available online.

1 Incidentally, Rosenbach favorite Benjamin Franklin was one of the first scientists to write about the link between volcanic eruption and climate change, according to Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World by Gillen D’Arcy Wood. But while his short, hastily written paper on the topic got him an honorary membership into the Manchester Metereological Society in England, his theory didn’t really catch on.

2 Not coincidentally, Arctic exploration captivated the imagination of many other authors of Shelley’s period; the melting polar ice permitted greater access to the Arctic Circle and renewed interest in locating the Northwest Passage.

3 Volcanoes, with all their terrifying and deadly power, would become a popular motif in other monstrous tales of the nineteenth century: at the end of the end of Varney the Vampire, a penny-dreadful inspired by John Polidori’s own Villa Diodati spooky story, the undead Varney is finally destroyed when he flings himself into a volcano; an early draft of Dracula had an erupting volcano bring about the Count’s demise, as noted in this wonderful feature on our Frankenstein & Dracula exhibition in Earther, the environmentally-focused website launched by Gizmodo media group.