Alice Dunbar-Nelson faced many personal struggles, but she always fought back against the sexism and racism that marred U.S. society throughout her lifetime.

“Clothed with Strength and Dignity”

Fighting Social Injustice

This exhibition addresses topics including intimate partner abuse, sexual assault, and race-based violence.

IN HER SOCIAL JUSTICE ACTIVISM, Dunbar-Nelson battled lynching, challenged the Ku Klux Klan, organized for enfranchisement and women’s voting rights, lobbied for Black history in the K–12 curriculum, fostered improvements in international race relations, and sought better benefits for Black veterans returning home from World War I. Her service appointments and political campaigns included work for the National Association of Colored Women, the National Federation of Colored Women’s Club, the Woman’s Suffrage Party of York County, the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, the NAACP, the Republican State Committee of Delaware, and the American Interracial Peace Committee.

Despite her literary accomplishments and political organizing skills, Dunbar-Nelson struggled financially for much of her adult life. Living on loans and relying on precarious nonprofit work and dwindling royalty checks from her early publications, Dunbar-Nelson found that her efforts to achieve a life of economic stability were impeded by the same systemic racism and sexism that she worked so diligently to challenge. Nonetheless, as a survivor of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and police violence, and having overcome unfair career setbacks in addition to perpetual discrimination, Alice Dunbar-Nelson led a life of remarkable achievement.

34. Dr. John Francis (1856-1913), autograph letter signed to Maj. Richard Sylvester

Washington, D.C., 24 September 1901

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.5.121

(For information about this object, see the label for object 35.)

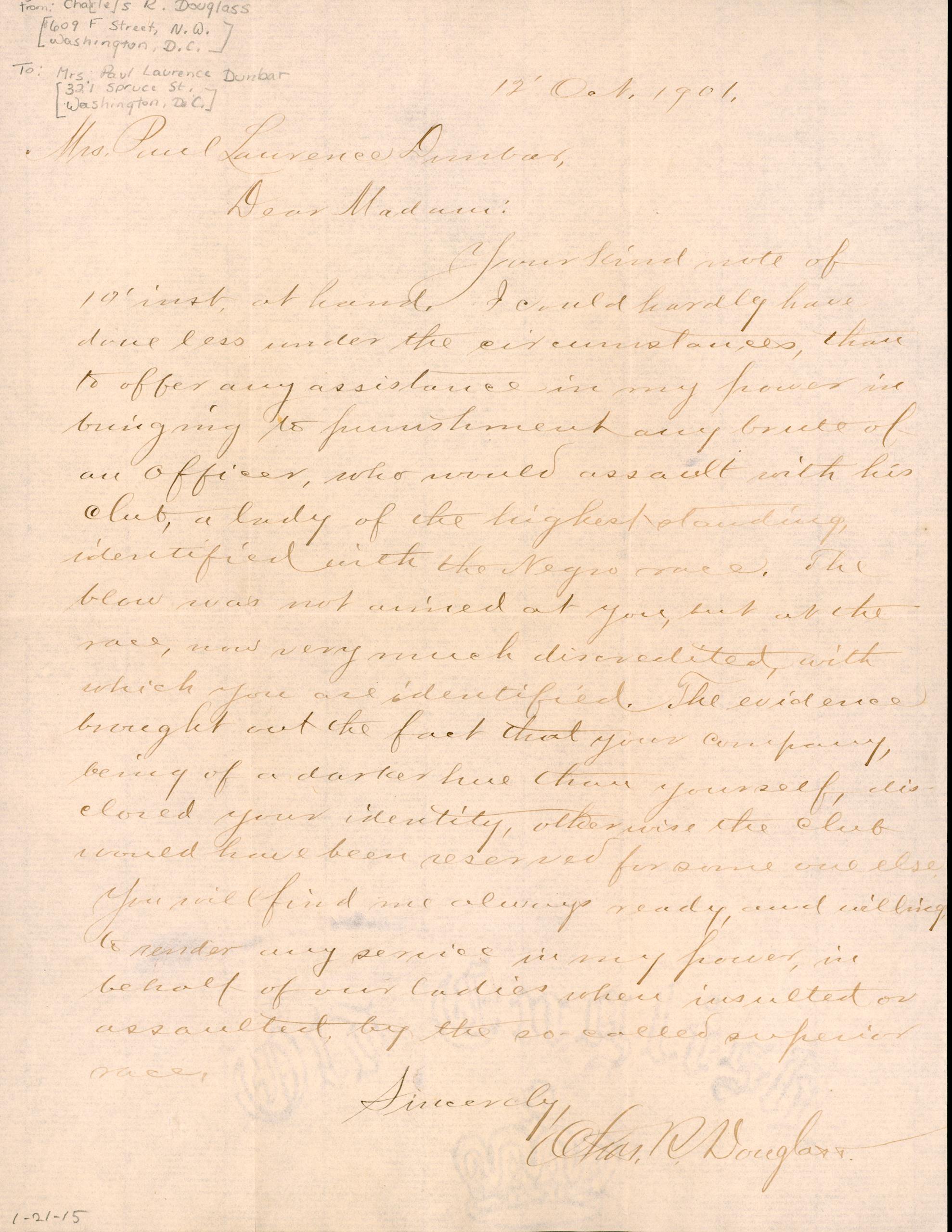

35. Charles R. Douglass (1844-1920), autograph letter signed to Alice Dunbar

Washington, D.C., 12 October 1901

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.5.122

The legal case between Alice Dunbar-Nelson and William Kemp offers a clear record of how women of color fought back against race-based police violence generations before the protests of the 1960s and the modern Black Lives Matter movement. Dunbar-Nelson sought legal action against Private William Kemp for what she alleged was an unwarranted assault on her with a police baton.

On September 17, 1901, Dunbar-Nelson was reportedly assaulted by Kemp during a panic that arose among a crowd of 20,000 people waiting to view President William McKinley as his body lay in state at the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C. Kemp, along with several white witnesses, claimed that Dunbar-Nelson had become violent, provoking the attack—a dubious accusation, considering that Dunbar-Nelson was not charged with a crime at the time of the incident. Numerous other witnesses, in fact, affirmed that she had been wrongfully assaulted without provocation. Some of these witnesses, like Dr. John Francis, a professor in the Medical School of Howard University and a member of the faculty at the Freedmen’s Hospital, wrote in support of Dunbar-Nelson’s character. The blow, according to reports, was severe enough to draw blood from her head.

The correspondence between Richard Sylvester, major and superintendent of the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia; John H. Ross, District of Columbia police commissioner; Charles R. Douglass, youngest son of Frederick and Anna Murray Douglass; and Dunbar-Nelson sketch out details of an incident all too familiar today. Structural racism in the justice system led to the case being dismissed; the officer was not reprimanded in any meaningful way.

36. Charles R. Douglass (1844-1920), typed letter signed to John H. Ross

Washington, D.C., 15 January 1902

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.5.122

Charles R. Douglass was the third son of Frederick and Anna Murray Douglass and a soldier in the Civil War. He served in Washington, D.C., as one of the first Black clerks in the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, otherwise known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, the chief agency tasked with assisting emancipated Black men and women during Reconstruction. By the time of this correspondence, Douglass had been working for the federal government’s Bureau of Pensions for more than a decade.

37. American Interracial Peace Committee (1927-1931), typescript press release

Philadelphia, 1928

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.26.456

Alice Dunbar-Nelson served as executive secretary for the American Interracial Peace Committee (AIPC) from 1927 to 1931 at its headquarters in Philadelphia. It was her last paid position and a campaign that she ardently believed in and worked hard to advance. A project of the Quaker-run American Friends Service Committee (ASCF), the AIPC was formed in part to address issues of diversity and representation both within the organization and among the broader public. Dunbar-Nelson’s ideas were ultimately too radical for the AIPC, and there were philosophical differences among the racially mixed board of directors that could not be resolved. Due to a lack of funding from the ASCF, the AIPC was forced to close by the time the Depression began.

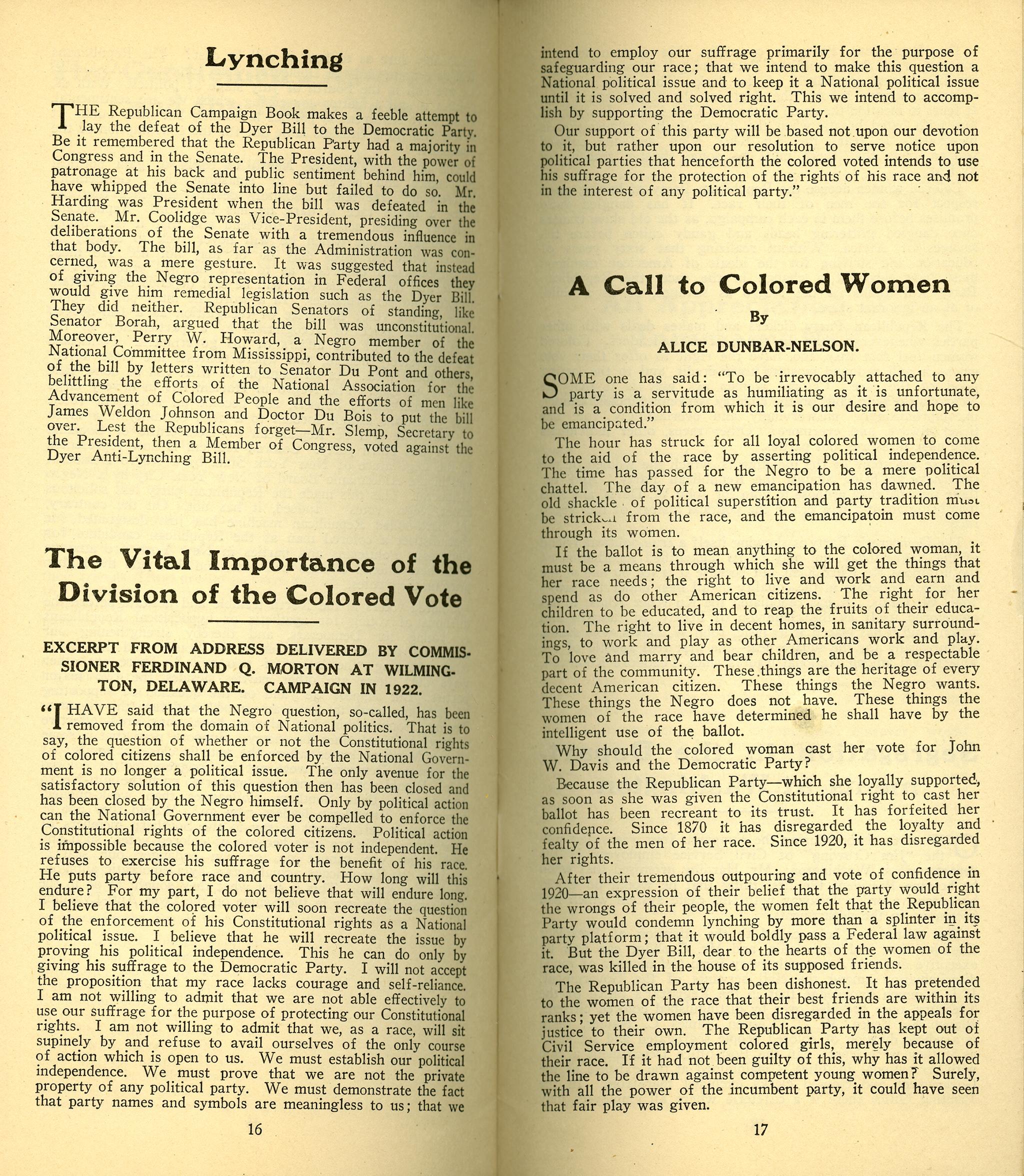

38. Democratic National Committee (1848-present), Facts for colored voters

New York: M. B. Brown Printing & Binding Co., 1924

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

OCLC 1126315345

Produced by the Colored Voters’ Bureau of the Democratic National Committee, this political pamphlet includes excerpts from the writings of author and activist James Weldon Johnson, educator and administrator Roscoe Conkling Bruce, and Dunbar-Nelson. The selections are largely supportive of the Democratic Party and its platform. It is an interesting example of how President Warren G. Harding’s dismissal of the serious threat posed by the Ku Klux Klan began turning many Black voters away from the Republican Party decades before that party’s “Southern strategy,” which embraced anti-Black racism following the modern civil rights movement and led to a mass exodus of Black voters from their longstanding allegiance to the GOP.

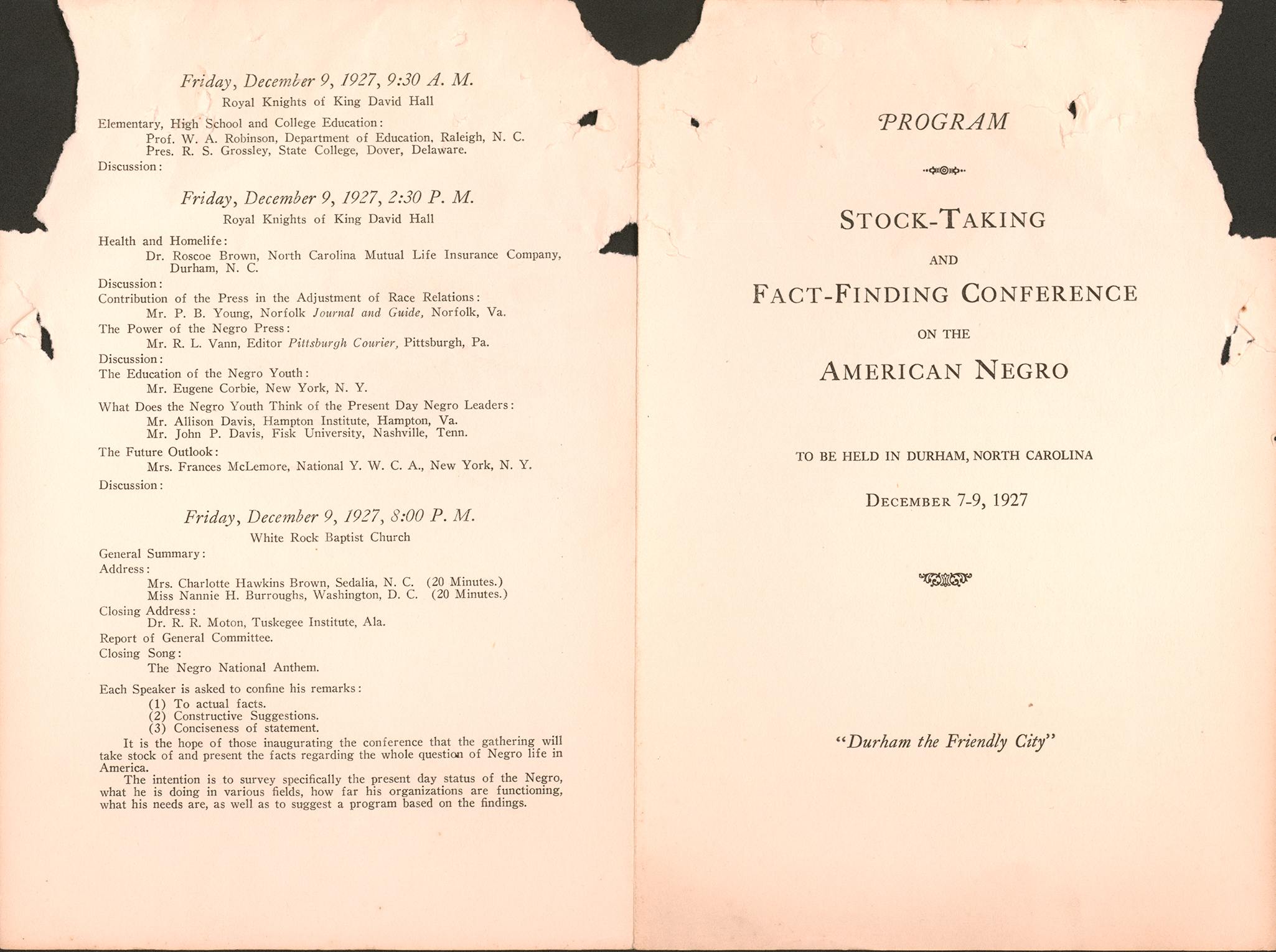

39. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1919 to present), sponsor, “Conference program for the annual stock-taking and fact-finding conference on the American negro”

Durham, North Carolina, 9 December 1927

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.27.461

Dunbar-Nelson was the official compiler for the Stock-Taking and Fact-Finding Conference on the American Negro, held December 7–9, 1927, in Durham, North Carolina. This conference was more than academic exchange of ideas. According to this program, it intended to “survey specifically the present day status of the Negro, what he is doing in various fields, how far his organizations are functioning, what his needs are, as well as to suggest a program based on the findings.” The roster of renowned presenters included A. Philip Randolph and Arthur Alfonso Schomburg speaking in the “Work and Wages” session, Carter G. Woodson discussing issues of social justice and the criminal justice system, and W. E. B. Du Bois, who spoke on politics.

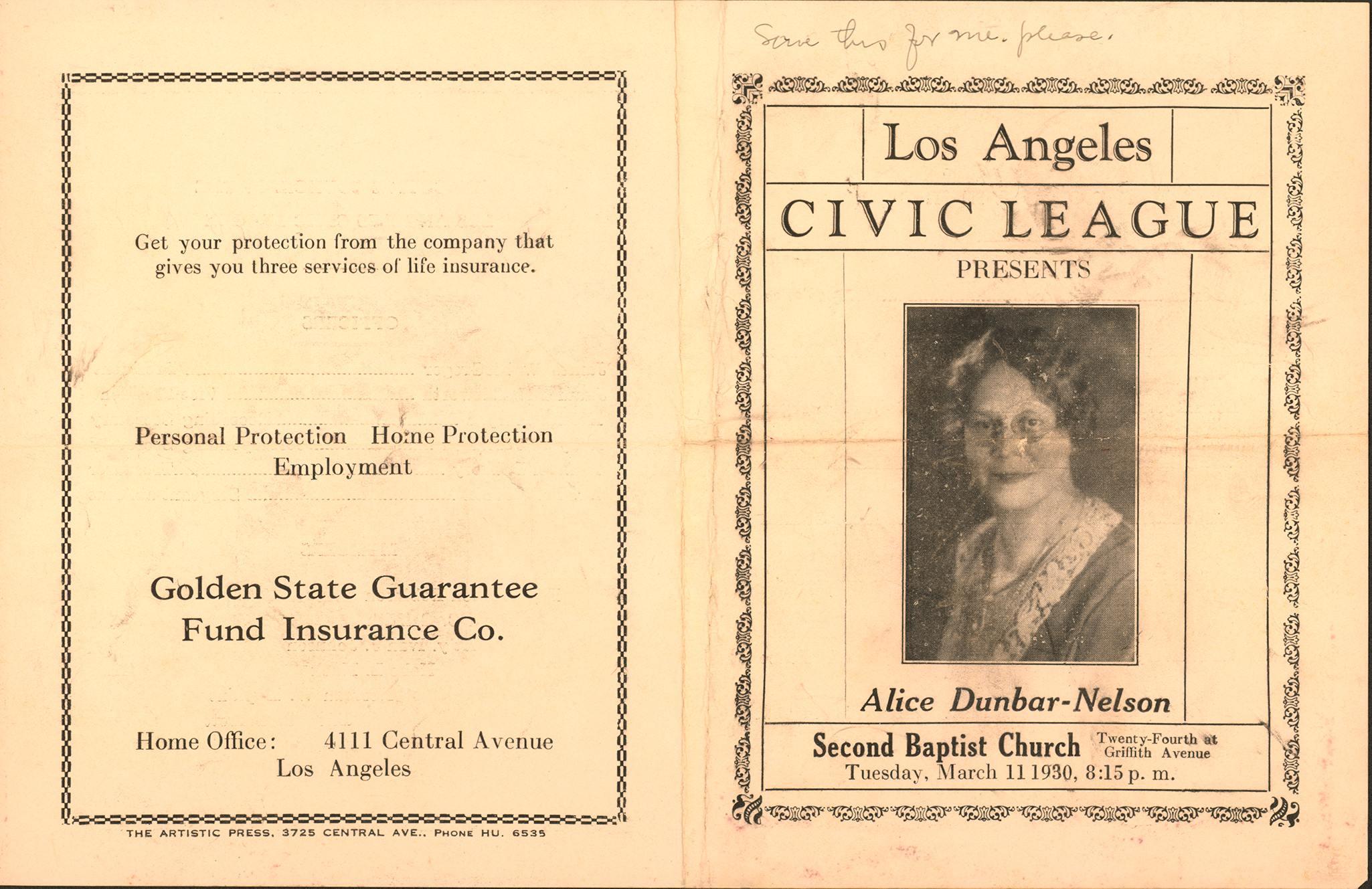

40. Los Angeles Civic League (ca. 1900-1940), promotional flier for Alice Dunbar-Nelson Speaks

Los Angeles, California, 11 March 1930

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.27.461

One of several Black political organizations that were formed in Los Angeles during the 1920s, the Los Angeles Civic League was among the first in the city to be supportive of interracial work. Not to be confused with the consortium of Los Angeles–based women’s clubs that was started much earlier under the same name (later the Civic Federation), the Los Angeles Civic League of the 1930s invited notable Black speakers from across the nation to address lectures and readings to a Los Angeles audience. This speaking engagement allowed Dunbar-Nelson to realize a yearning she had to visit California; she noted her affinity for the state in her diary.