Black America’s most famous 19th-century poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar, fell in love with Alice Dunbar-Nelson in 1895 after seeing a sketch of her in a magazine.

Sunshine and Shadow

Surviving Intimate Partner Violence

This exhibition addresses topics including intimate partner abuse, sexual assault, and race-based violence.

THEIR COURTSHIP, which unfolded over elegantly written correspondence, is a lasting illustration of the literary admiration that marked their relationship. Yet their courtship and marriage concealed much more tragedy than was visible on the surface.

On November 16, 1897, Paul Laurence Dunbar raped the then-22-year-old Dunbar-Nelson. The physical abuse she suffered at his hands may have resulted in her being unable to bear children.

She still married Dunbar in the spring of 1898, despite disapproval from both her own mother and Dunbar’s mother. This outcome reflected late 19th-century social expectations of womanhood, marriage, respectability, and sexual purity, combined with a deep affection she maintained for the poet, both during his life and after his death. Though she separated from Dunbar after a violent incident that left her hospitalized in 1902, Dunbar-Nelson continued to correspond with him and, following his death in 1906, became one of the most important advocates for his literary work.

The violence inflicted on Alice Dunbar-Nelson by Paul Laurence Dunbar nearly resulted in her death. Had she not escaped the cycle of intimate partner violence, the important educational, political, and literary work she completed between 1902 and 1935 never would have happened. The nation would have lost an important voice for Black women’s issues—and most of the artifacts you see on display in this exhibition would not exist.

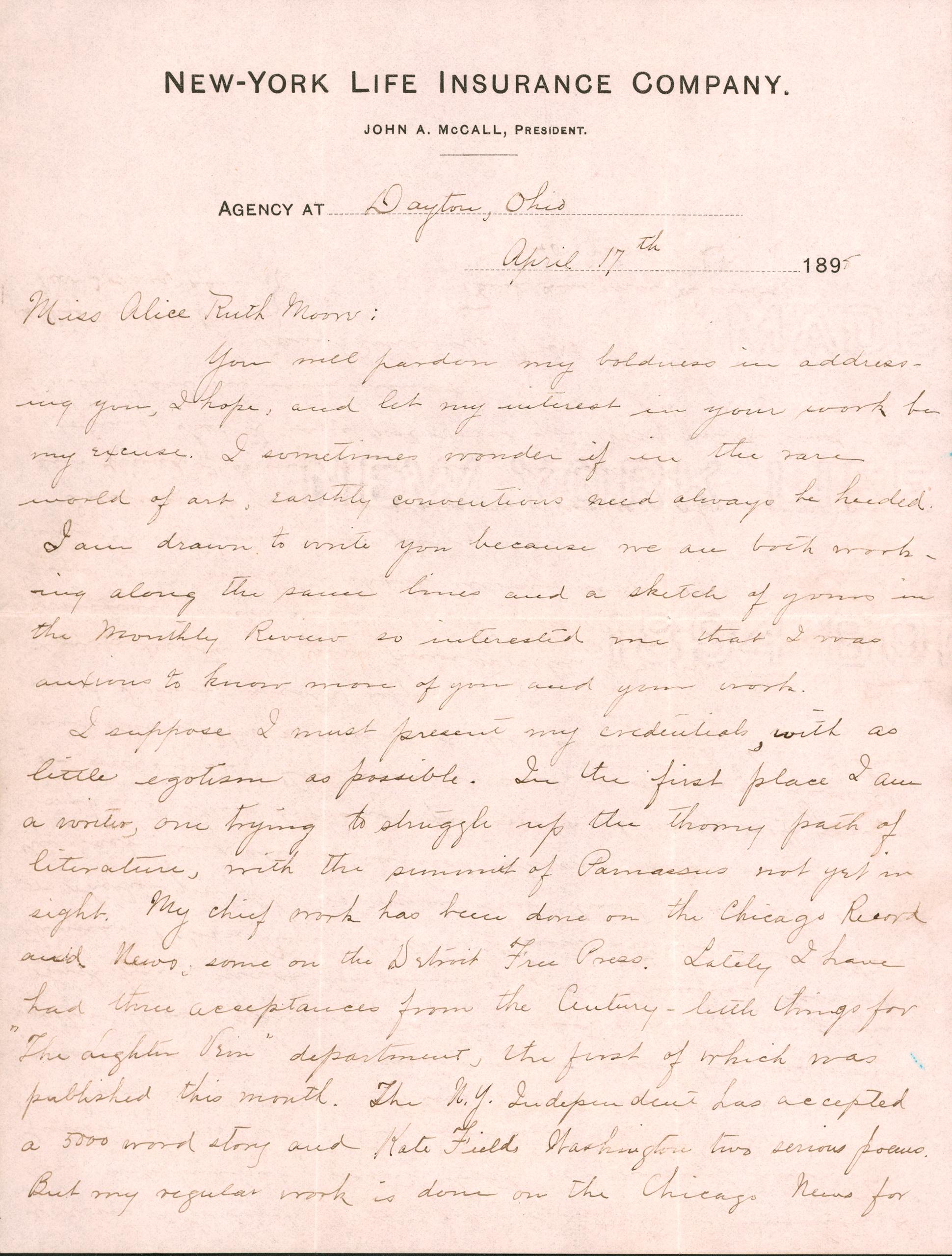

41. Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), autograph letter to Alice Ruth Moore

Dayton, Ohio, 17 April 1895

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.1.1

The complicated relationship between Paul Laurence Dunbar and Dunbar-Nelson—then Alice Ruth Moore—began with this letter. With a tone of eloquent civility masking feelings of possessiveness and competition, the letter foreshadows a set of power dynamics that would later come to define their courtship and marriage, as well as the physical and sexual abuse Dunbar-Nelson suffered at Dunbar’s hands. “Miss Alice Ruth Moore,” it opens, “You will pardon my boldness in addressing you, I hope, and let my interest in your work be my excuse. I sometimes wonder if in the rare world of art, earthly conventions need always be heeded.” Dunbar-Nelson was intrigued, flattered, and delighted by Dunbar’s advances; nonetheless, in her usual way, she quickly redirected the tone of their correspondence toward a discussion of the day’s intellectual and political concerns, all the while maintaining an air of flirtation.

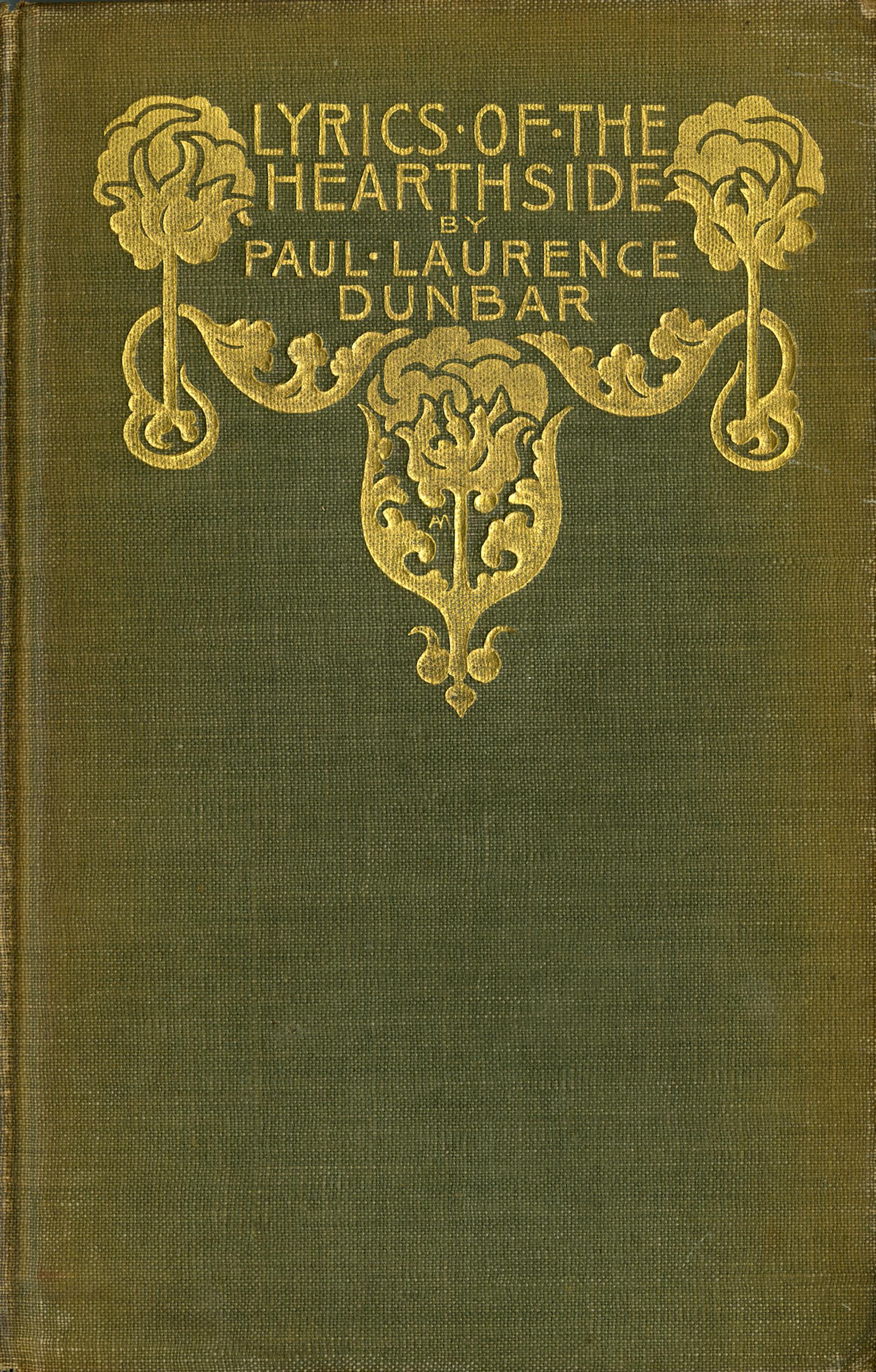

42. Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), Lyrics of the hearthside

New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1899

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

PS1556 .L7x 1899

“Love me & though the winter snow shall pile / and leave me chill / thy passion’s warmth shall make for me, meanwhile / a sun-kissed hill,” reads the romantic inscription scrawled on the flyleaf of this presentation copy of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s Lyrics of the Hearthside, given by the author to Dunbar-Nelson, his wife at the time. The excerpt is a stanza from his poem “Love’s Apotheosis”—the opening poem of the book. Beautiful and haunting, the lines portend the eventual demise of their marriage, which would occur over the next few years. An image of a handsome Dunbar appears in the frontispiece, fashionably dressed in his trademark attire—all the more chilling given that an escalating level of assault against his wife was hidden between the lines of elegantly crafted verse. As demonstrated in Dunbar-Nelson and Dunbar’s relationship, intimate partner violence occurs in a cycle that can move back and forth between a “honeymoon phase” and verbal, physical, and sexual violence.

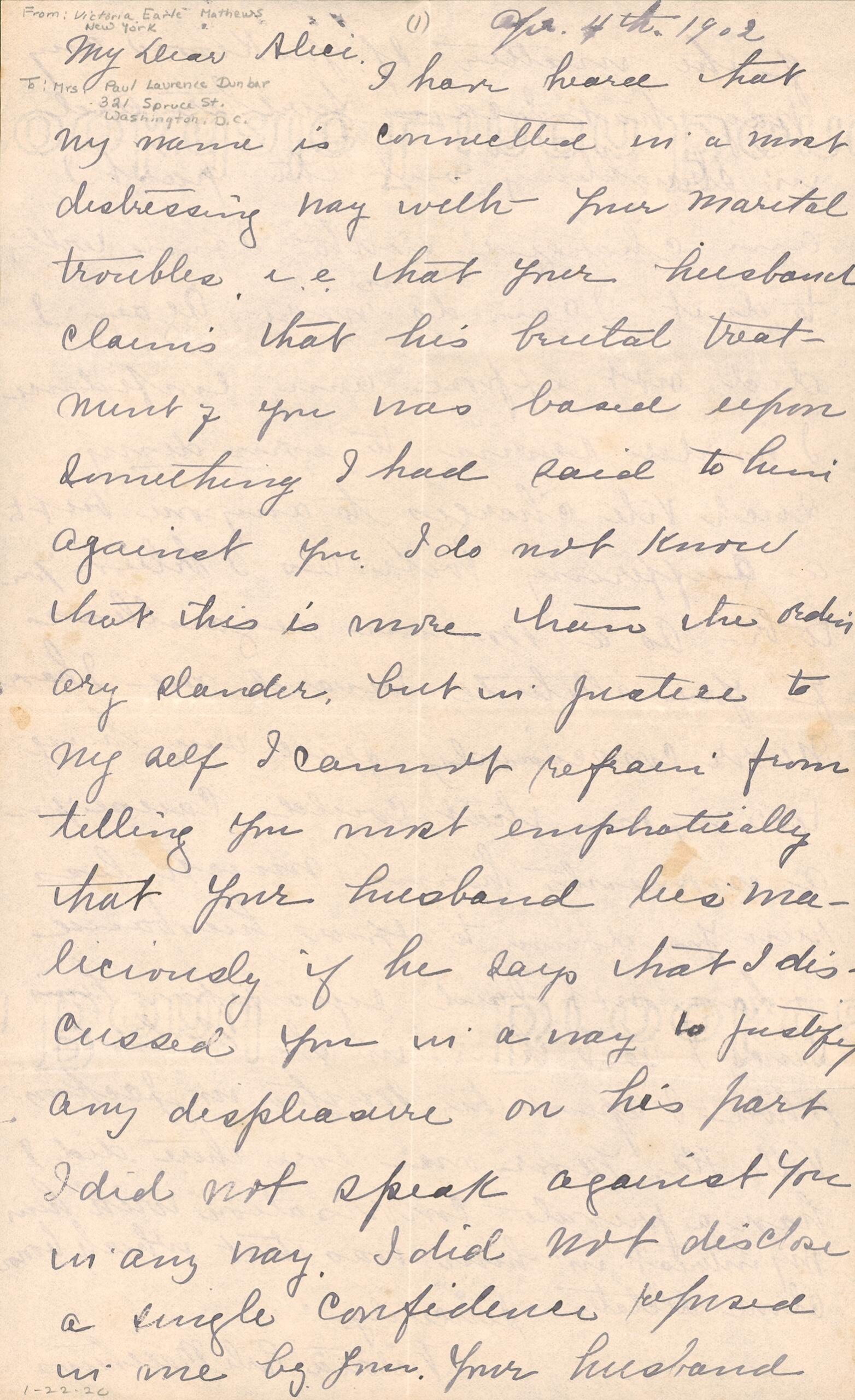

43. Victoria Earle Matthews (1861-1975), autograph letter signed to Alice Dunbar

New York, 4 April 1902

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.5.122

Dunbar-Nelson separated from Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1902. This distressed letter from fellow journalist and activist Victoria Earle Matthews shows both the tumultuousness of an abusive marriage in collapse and the expressed solidarity and sisterhood of a close companion. Matthews opens the letter with an impassioned denial of gossip that has circled back to her. She writes that her name was being mentioned in connection with their marriage “in a most distressing way . . . i.e. that your husband claims that his brutal treatment of you was based upon something I had said to him against you.” Matthews fervently denies the perceived breach of confidence by telling her friend that her husband “lies maliciously” and cannot be trusted.

44. Women’s Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Church (1884-1940), Calendar

Ashland, Ohio, 1906

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.27.469

Mourned by the nation, Paul Laurence Dunbar died in 1906 at the young age of 33 from tuberculosis. Although they had been separated for over three years by the time of his death, Dunbar-Nelson continued lecturing and writing on the importance of her late husband’s contributions for the rest of her adult life. This calendar from the Women’s Home Missionary Society shows the reach of memorials that were held in his home state after his passing.

Are you, or is someone you know, struggling with intimate partner violence?

Help is available.

Domestic violence is a public health crisis in Philadelphia.

Learn more here.

Are you, or is someone you know, struggling with intimate partner violence?

Help is available.

If you are in immediate danger, always call 911.

WOAR – Philadelphia Center Against Sexual Violence works to eliminate sexual violence and provides counseling for survivors. Learn more at woar.org or call their 24-hour confidential hotline: 215-985-3333.

The Philadelphia Domestic Violence Hotline is a citywide, 24-hour resource for crisis intervention, safety planning, and support. 1-866-723-3014 (TTY 215-456-1529).

Women Against Abuse is Philadelphia’s leading domestic violence service provider. It operates the city’s only emergency safe havens and legal center for people experiencing abuse. Learn more at womenagainstabuse.org.

Domestic violence is a public health crisis in Philadelphia.

Philadelphians place more than 100,000 911 calls relating to domestic abuse each year.

Philadelphia courts receive more than 12,000 requests for Protection from Abuse orders each year.

The Philadelphia Domestic Violence Hotline has to turn away 10,000 callers every year seeking safety because the city has only 200 shelter beds for domestic violence survivors.

Each year for the past five years, 19 people have been killed by domestic violence in Philadelphia.

On an average night, 250 people experiencing homelessness in Philadelphia self-report as victims of domestic violence.

A 2015 study found that in the United States, about 1 in 4 women and 1 in 10 men experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner and reported an intimate-partner-violence-related impact during their lifetime.

For more information, and details on how to help, visit womenagainstabuse.org.