Generations after her death in 1935, Alice Dunbar Nelson is most remembered as a poet and writer.

Writer and Poet

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Finds Her Voice

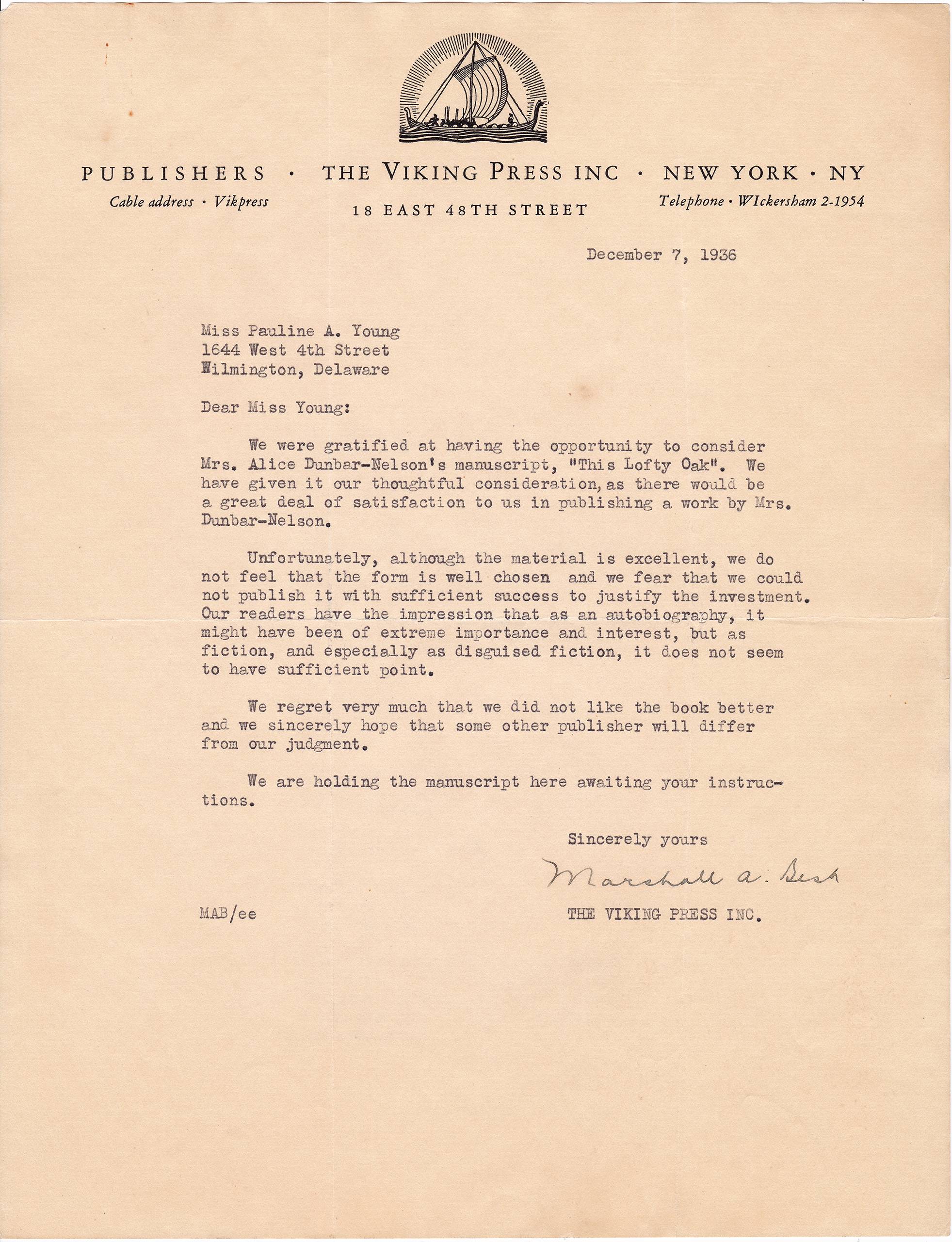

DURING HER LIFE, Dunbar-Nelson’s two published short story collections were well received by critics, and she enjoyed success editing a notable collection on Black literary heritage. Despite these achievements, publishers refused to print her two novellas and her novel, This Lofty Oak.

The literature Alice Dunbar-Nelson produced did not fit neatly into what was at that time categorized as “race literature.” Instead, Dunbar-Nelson’s writings crossed boundaries imposed by social conventions and the marketplace in which she operated. She pushed beyond subjects and themes considered commercially viable for literary fiction.

This Lofty Oak remains unpublished. Before her passing in 1935, Dunbar-Nelson left the manuscript to her niece Pauline Young to finish the edits and obtain publication. Young reached out to five publishing companies, most of which had previously published books written by Alice’s long-deceased husband Paul Laurence Dunbar. These companies refused to print the manuscript. They considered the text, in the words of one company, “unsuited” for publication, since it was “posthumous” work, and “very long novels are a drag on the market, and mean continuous expense and trouble in submitting them.”

Dunbar-Nelson’s lack of success publishing her novel says more about the publishing industry’s discriminatory practices than her abilities as an author. In the 1980s, many decades after her death, historians and writers began taking a fresh look at Dunbar-Nelson’s work in an effort to give her the place in American literary history that her writings merit. The large archive she left behind, including manuscripts of many of her works, has proven essential in the re-evaluation of her literary legacy.

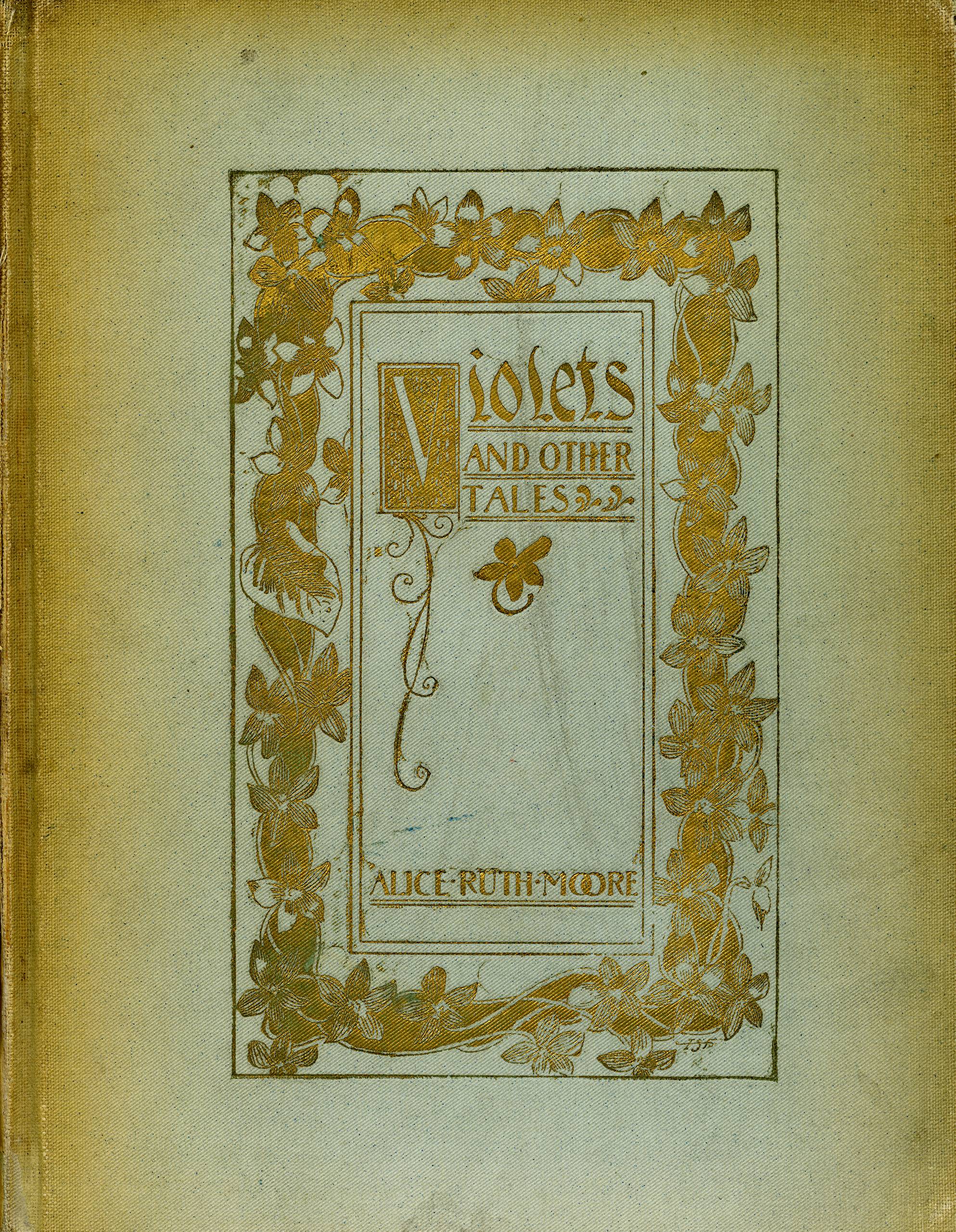

Boston: Monthly Review, 1895

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

PS3507 .U6228 V56x 1895

A lifelong writer of remarkable ability and skill, 20-year-old Alice Ruth Moore burst onto the New Orleans literary scene in 1895 with her first book, Violets and Other Tales. The collection of short stories, poems, and essays garnered widespread acclaim from establishment critics and the Black press alike. Much of the book exhibits a Victorian romance and narrative eloquence. Yet with piercing witticism, tacit defiance, and an openness to experimentation, Violets and Other Tales also converses with literary modernism. This first-edition copy bears ownership stamps from both her and her soon-to-be husband, the famous poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.

New Orleans, Louisiana, 1895

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.12.233

Dunbar-Nelson and her family compiled reviews of her first published work in several scrapbooks.

The reviews in this scrapbook reveal much about Dunbar-Nelson’s early writing, as well as the problematic nature of the author’s rising fame. At once steeped in tradition and ahead of its time, Violets easily stands on its own literary merits. Yet many contemporaneous reviews note the author’s physical beauty as a selling point. The objectification of women often factored into the marketing of women writers, especially women of color. Cognizant of the industry’s superficiality, Dunbar-Nelson understood how to take advantage of her attractiveness to the benefit of her own marketability.

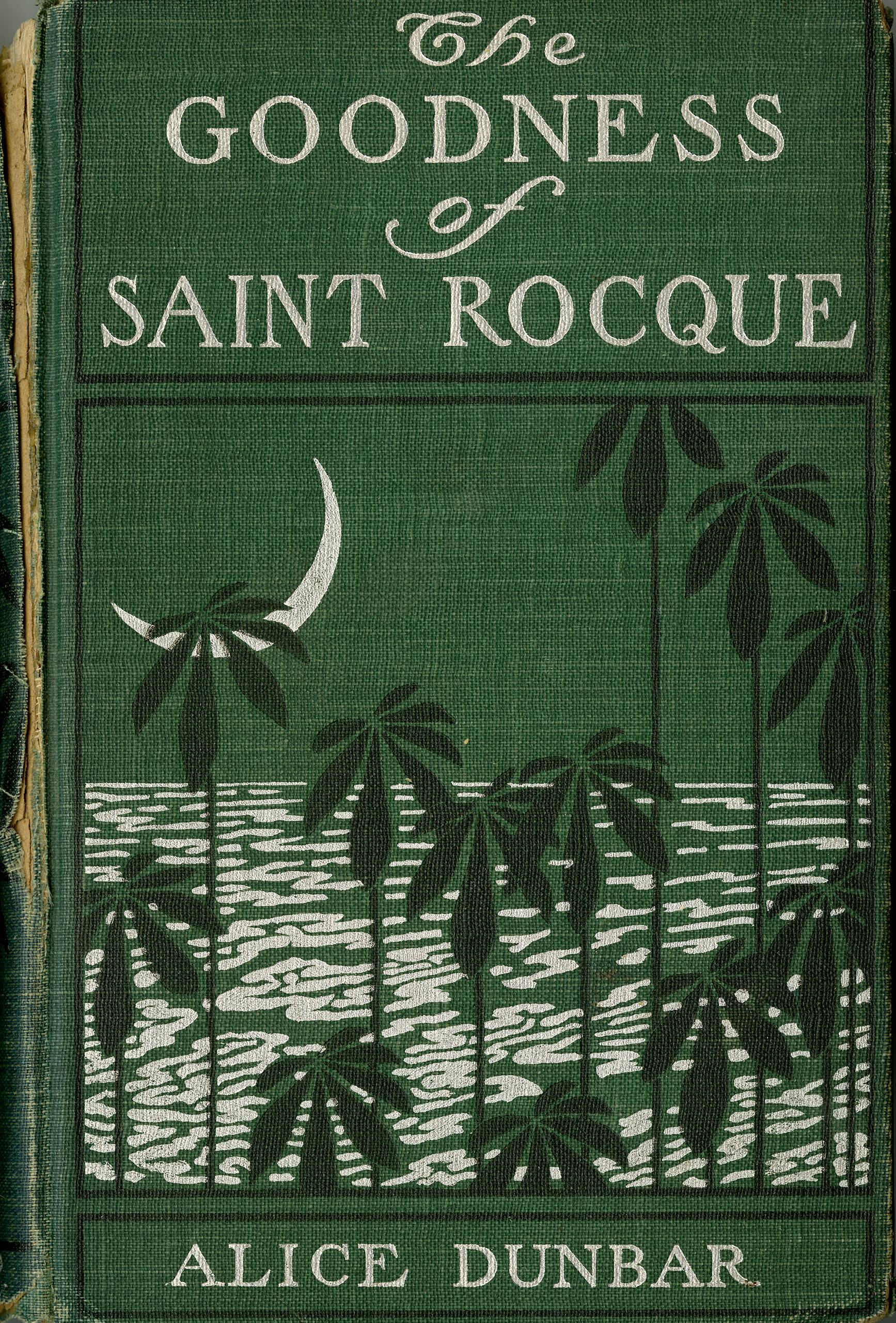

3. Alice Dunbar [Alice Dunbar-Nelson] (1875-1935), The goodness of St. Rocque and other stories

New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1899

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections Museums

PS3507.U6228 G66 1899

Not long after her marriage to poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, Dunbar-Nelson followed the success of Violets with the publication of the similar, yet somewhat more complex The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories. Published by her husband’s publisher, this collection contains subtle sketches that are weighty in substance. Stories such as “Tony’s Wife” and the revised and republished “Titee,” for example, contend with everything from domestic violence and sexism to delinquency and societal prejudice.

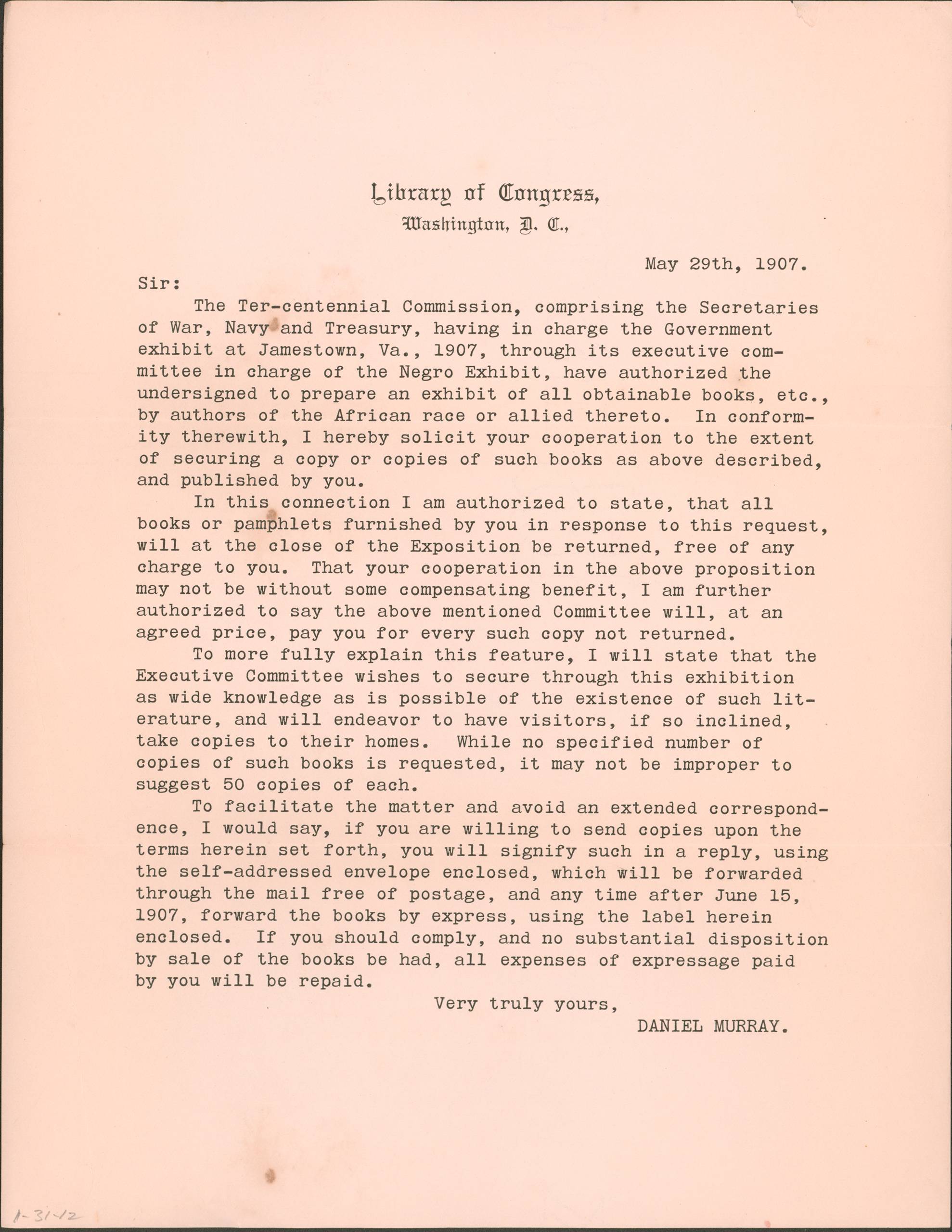

4. Daniel A. P. Murray (1852-1925), typescript letter signed to Paul Laurence Dunbar

Washington, D.C., 29 May 1907

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.5.137

Daniel Alexander Payne Murray sent this letter as part of his committee’s charge to collect and exhibit works of Black literature for the Library of Congress. Murray had had prior experience doing this work as curator of the Negro Authors exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition, which involved a larger project of building the Library of Congress’s “Colored Authors’ Collection.” This letter was not addressed to Dunbar-Nelson directly, suggesting that it was a generic letter sent out to numerous writers of color. In it, Murray asks that works be sent to the Library of Congress for an “exhibit of all obtainable books, etc. by authors of the African race.”

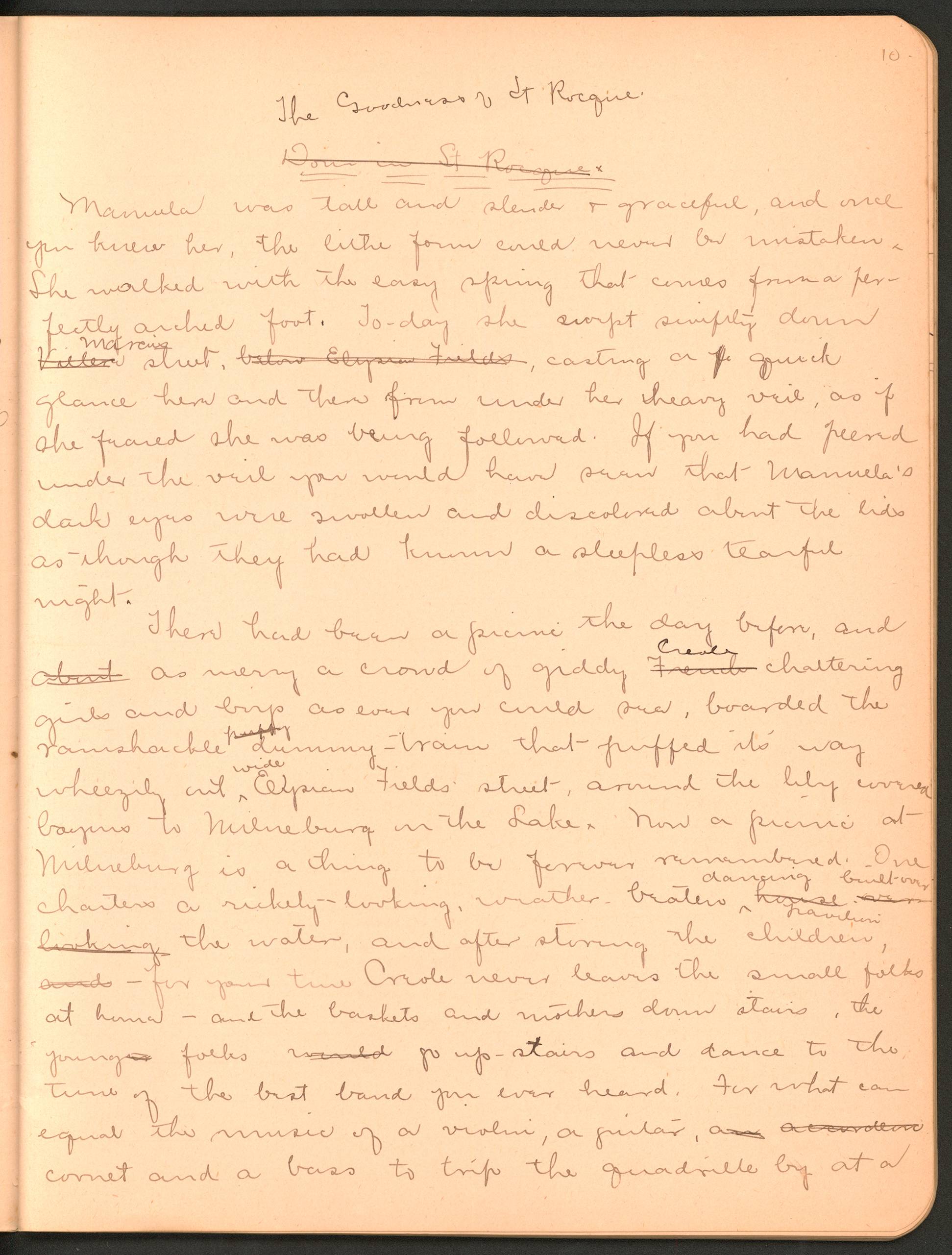

5. Alice Ruth Moore [Alice Dunbar-Nelson] (1875-1935), The goodness of St. Rocque: autograph manuscript, “The Goodness of St. Rocque,” short story

Brooklyn, New York] 16 July [1898]

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.23.437

“The Goodness of St. Rocque,” the story that gives her second published volume of short stories its title, is one of Dunbar-Nelson’s most compelling offerings in the genre of “local color fiction.” This genre, otherwise known as regional literature, is characterized in part by its aim of capturing the feel or the spirit of a specific locale. In this story, the author conveys the spirit of Louisiana’s Creole culture. As the place of her birth, New Orleans, and Louisiana more broadly, was central to Dunbar-Nelson’s cultural identity. This original manuscript documents the careful attention she gave to the process of revision. The title of the story, “Down in St. Rocque” is changed to “The Goodness of St. Rocque.” The word “French” is replaced with “Creole.”

6. Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935), “I am an American!”: typescript

[Wilmington, Delaware] [1920-1928]

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.23.425

This poem, written by Dunbar-Nelson for the Associated Negro Press around 1916, was one of at least two written in response to a popular earlier poem by Russian immigrant Elias Lieberman that sought to write immigrants in the narrative of U.S. life. Rather than contradict the message of Lieberman’s poem, which itself was a progressive statement about the value of social acceptance, Dunbar-Nelson crafted a verse she hoped to append to Lieberman’s work, insisting that African Americans and Native Americans contributed to the rise of the U.S. republic and thus deserve the benefits of full membership in the body politic. The verse encapsulates both the pride she felt for her race and the optimism she maintained for the nation’s future in the closing lines: “I am proud of my past; / I hold faith in my future! / I am a Negro! / I am an American!”

Dunbar-Nelson was heavily invested in discourses on patriotism and the idea of who qualifies as an American. Like many in her generation—the first following emancipation—Dunbar-Nelson felt that being a citizen of the United States carried tremendous consequences as well as responsibilities. She took those responsibilities very seriously, working tirelessly to help the nation collectively recognize the value of Black citizenship. This effort meant, in part, celebrating the patriotism of the Black community. Bringing her knowledge of Black history to bear, she also challenged those who, in their revisionist formulations of patriotic sentiment, ignored contributions of people of color to this nation’s history.

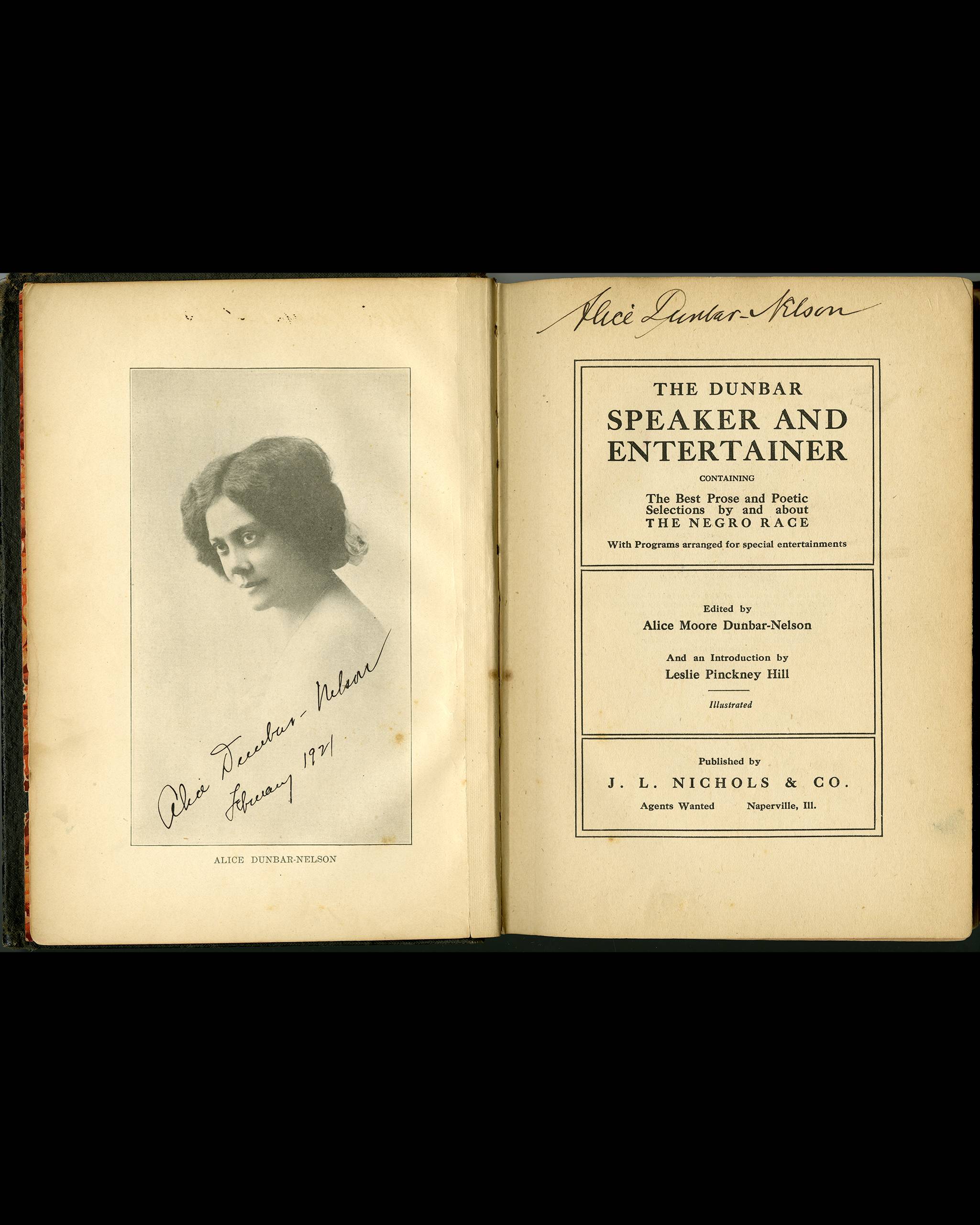

7. Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935) and Leslie P. Hill (1880-1960), The Dunbar speaker and entertainer: containing the best prose and poetic selections by and about the Negro race, with programs arranged for special entertainments

Naperville, Illinois: J. L. Nichols & Co., 1920

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

PN4305.N5 N4 1920

At the dawn of the Jazz Age of the 1920s, Dunbar-Nelson edited this fascinating collection of works expressly devoted to Black literature and culture. The anthology was compiled with entertainment in mind, but without losing sight of a larger mission to educate Black youth. The dedication of the book reads: “To the children of the race which is herein celebrated, this book is dedicated, that they may read and learn about their own people.”

In addition to samples of her own work, Dunbar-Nelson included writing by Frances E. W. Harper, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charlotte Forten Grimké, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and James Weldon Johnson. However, the anthology was not limited to Black authorship. Poems by William Wordsworth, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Walt Whitman, among others, offer a nuanced picture of interracial literary heritage in the reclamation of a shared history.

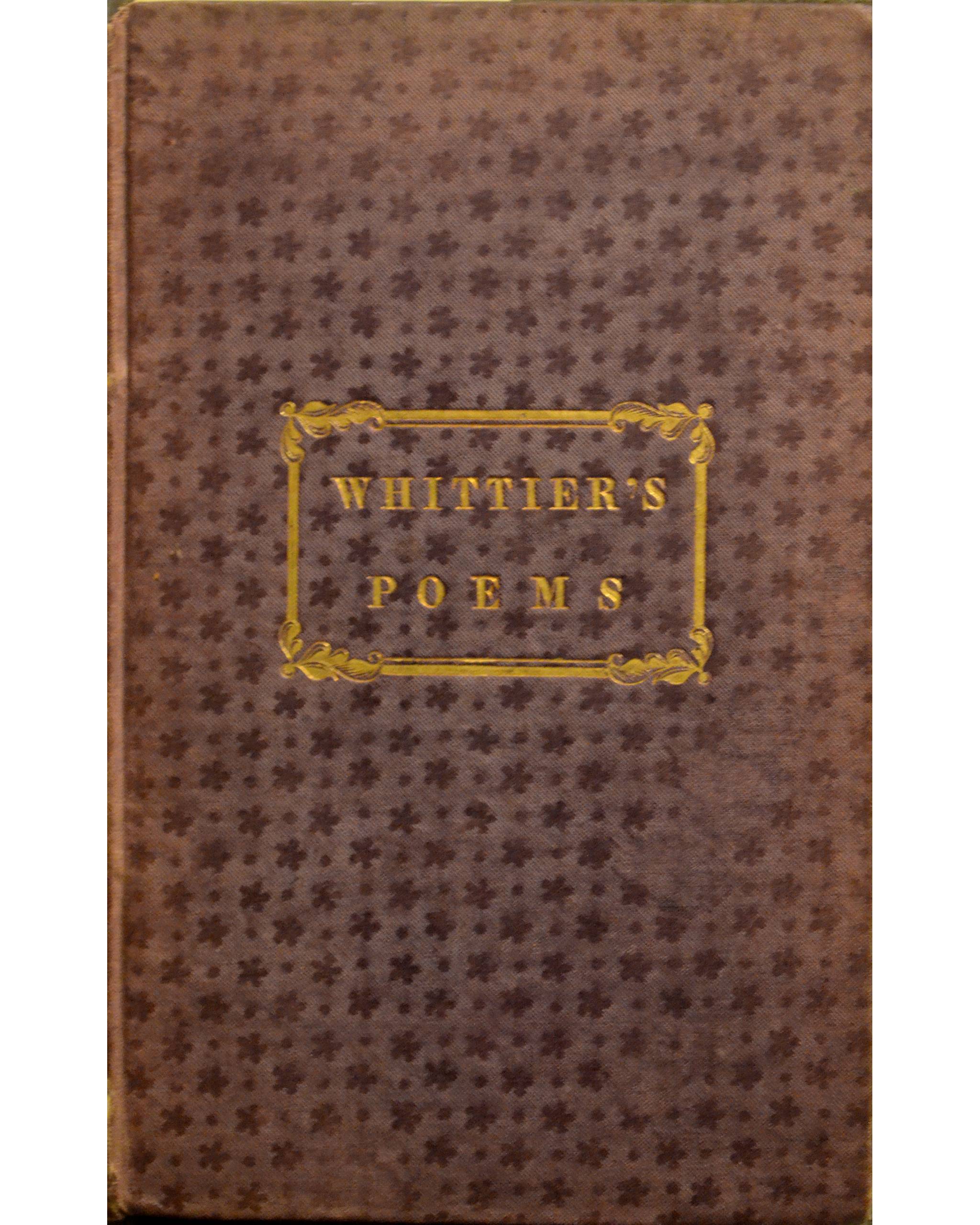

8. John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892), Poems written during the progress of the abolition question in the United States between the years 1830 and 1838

Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837

AL1 .W625p 837

John Greenleaf Whittier likely would have been pleased with his inclusion in Dunbar-Nelson’s 1920 anthology The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer. Once a beloved American poet who was taught in many public-school classrooms across the country, Whittier was one of the New England Fireside Poets of the late 1800s. He initially gained fame as an outspoken and controversial abolitionist advocate.

This book, published in Philadelphia in 1838, is filled with anti-slavery poetry that Whittier wrote to shape public opinion about the horrors of human bondage. The poems harshly condemn slavery and ask Americans to consider if the institution fits within the nation’s democratic principles.

9. Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935), Mine eyes have seen: typescript

[Wilmington, Delaware], 1917/18

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.20.364

This one-act play, first published in The Crisis in April 1918, is at once succinct and poignant. Dunbar-Nelson makes use of a diverse cast of characters to deal with issues of immigration, assimilation, masculinity, patriotism, violence against Black bodies, and the impact of disability. The play appears to draw from her personal experience of working with New York’s tenement housing communities during a period when she lived with fellow journalist and activist Victoria Earle Matthews in Brooklyn while teaching at the White Rose Mission. It is narrated around the difficult dilemma a Black family faces when the primary earner must decide whether to serve in World War I. The family’s immigrant neighbors all weigh in on the decision the family is facing, offering various commonly held perspectives on the war effort during the period.

Long believed to have enjoyed only a single performance at Howard High School in Wilmington, Delaware, promotional fliers in the collection and recent research have shown that the play was actually performed at least eight times between 1918 and 1926, with productions reaching as far as the Pilgrim Baptist Church of St. Paul, Minnesota.

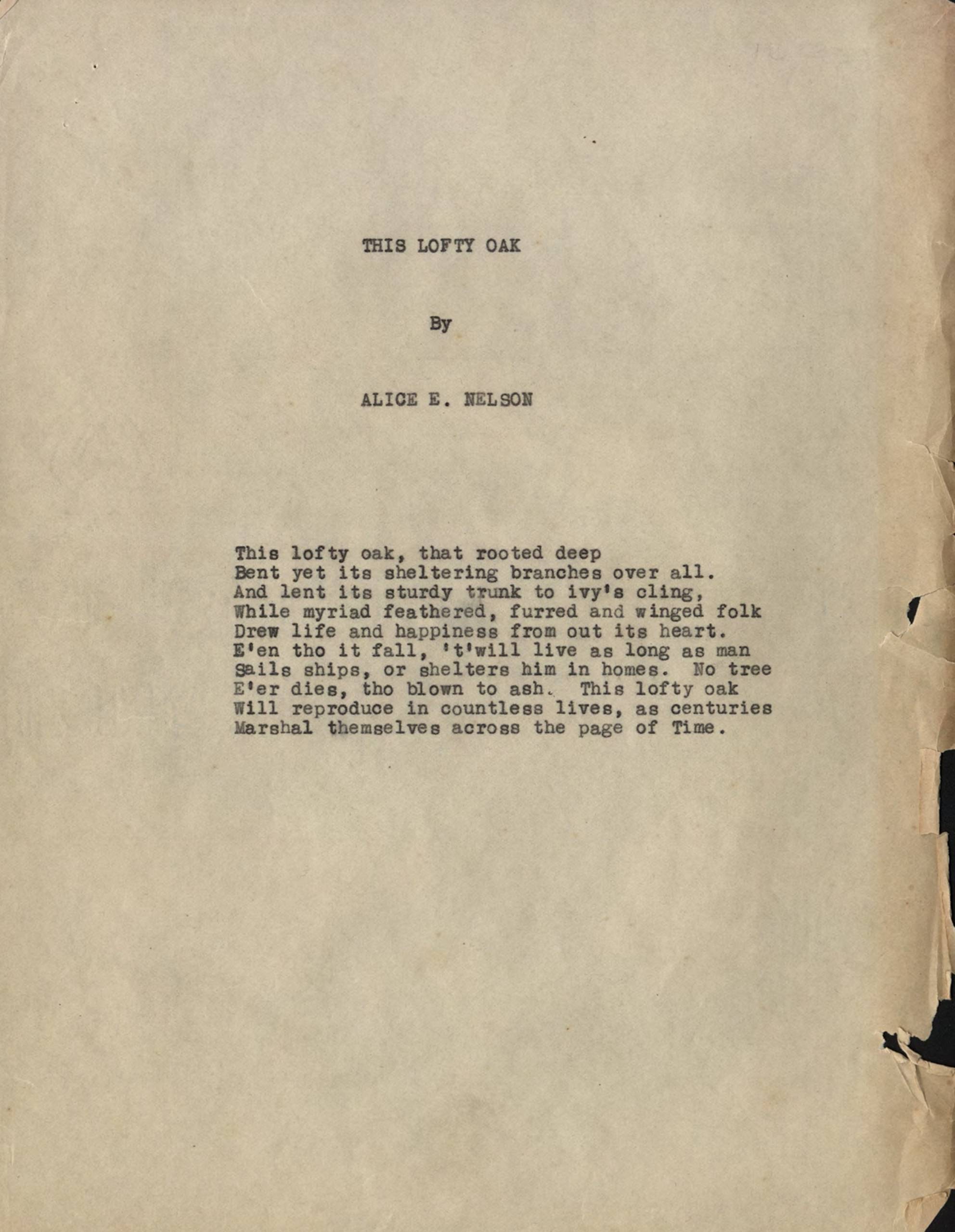

11. Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935), This Lofty Oak: typescript

Philadelphia, 1932

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.14.245

This Lofty Oak is Dunbar-Nelson’s unpublished novel honoring the life and career of educator Edwina Kruse of Wilmington, Delaware, with whom Dunbar had a long professional and romantic relationship.

Dunbar-Nelson creates the fictional character Fredericka to represent Kruse. The novel parallels elements of Kruse’s life, including her migration from San Juan, Puerto Rico; her passion for learning and teaching; and her lifelong commitment to Black institution building. Dunbar-Nelson imagined the manuscript becoming the next “great American novel.”

Dunbar-Nelson’s niece Pauline Young worked tirelessly to publish the manuscript after her aunt’s death, soliciting help from authors such as Carter G. Woodson and James Weldon Johnson. Several publishers refused. Though the manuscript remains unpublished, its existence emphasizes the impact and significance of Black women’s relationships in the early 20th century.

![Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935), “I am an American”: typescript

[Wilmington, Delaware] [1920-1928]

Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums

Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.23.425](https://rosenbach.org/virtual-exhibits/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/06.jpg)