Museums travel their objects all over the world, and the Rosenbach is no exception. But it’s especially interesting to travel around the world with an object that’s all about world travel. The object in question is our manuscript relating to Nakahama Manjiro’s travels from Japan to the U.S. and back from 1841-51, which we recently lent to the Sakamoto Ryoma Memorial Museum in Kochi, Japan. This project was more than a decade in the making, and the dream of two

people in particular: Junji Kitadai of Tokyo, a member of the Manjiro

Historic Friendship Society and all-around Manjiro expert; and Judy

Guston, our own Curator & Director of Collections, who became acquainted with

Mr. Kitadai during the lead-up to the Rosenbach’s own exhibition on its Manjiro manuscript 14 years ago. Fourteen

years sounds like a long time, but consider that the Rosenbach Manjiro

manuscript was last in Japan 101 years ago and you realize how significant a loan this is. Kathy did a great blog post about this manuscript about a year ago, and I’ll try not to duplicate her efforts too much. Instead, I’ll share with you some of the things we learned about Manjiro and our manuscript in our travels around his home island of Shikoku (and next week I’ll tell you more about the Sakamoto Ryoma Museum’s exhibition of Manjiro’s travels and manuscripts related to them).

The Kochi visitor’s information center built a wonderful representation of Shikoku with figures that capture each area’s significance. The city of Kochi is along the Pacific coast in the center, while Manjiro’s hometown is towards the bottom left corner of the island.

|

| Here’s the Manjiro figure near his hometown of Naka-no-hama (now Tosashimizu) on the south-western cape of Shikoku |

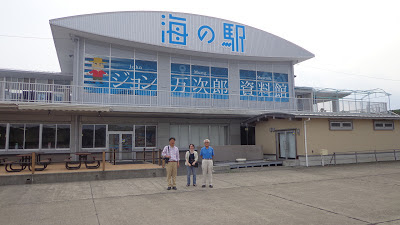

Judy, Junji Kitadai, and I traveled south to trace Manjiro’s route from his birthplace to his shipwreck to his route home after he returned to Japan. Our first stop was the John Mung (Manjiro’s anglicized name) Museum in Tosashimizu. The museum displays artifacts, period rooms, and models describing Manjiro’s travels, accomplishments, and legacy.

From the museum we headed to the site of Manjiro’s birth. The original house hasn’t survived, but a faithful recreation based on photographs was built next to where the original stood. Manjiro lived in this tiny house with his mother, brother, and sister, struggling to help support them and eventually leaving home to join the fishing expedition that would inadvertently send him around the world. When he returned to Japan, after his exhaustive debriefing at numerous cities, he finally made his way back to Kochi, and from there walked back to his old house for a reunion with his mother. Having followed that route for half a day by both train and car, Judy and I can tell you it’s a long and winding road that brought Manjiro home!

Finally, we headed to the town of Usa. The 14-year-old Manjiro embarked from this fishing village in 1841 with four companions, coasting along on the “black current.” This current normally betokened good fishing, but it proved treacherous on this voyage thanks to a terrible storm, carrying the fishermen and their small craft out to sea away from Japan, and stranding them on the inhospitable island of Torishima (nicknamed “Bird Island,” since albatross were the island’s only inhabitants–the one Manjiro site that Judy and I did not visit!).

|

| Manjiro portrait at the John Mung Museum, Tosashimizu |

Manjiro is such a celebrated historical figure that we saw his likeness everywhere. Most often he appeared in his red shirt and broad-brimmed hat, after a drawing done by the scholar and artist Kawada Shoryo, who recorded Manjiro’s story and created the manuscripts that now reside in the U.S. and Japan. The hat was from Manjiro’s adventure in California’s Gold Rush, in which he had participated after his whaling days had ended. We saw caricatures of this portrait of Manjiro on food packaging, tourist wayfinding information, and toys (which we really need for our museum shop!).

Manjiro is such a celebrated historical figure that we saw his likeness everywhere. Most often he appeared in his red shirt and broad-brimmed hat, after a drawing done by the scholar and artist Kawada Shoryo, who recorded Manjiro’s story and created the manuscripts that now reside in the U.S. and Japan. The hat was from Manjiro’s adventure in California’s Gold Rush, in which he had participated after his whaling days had ended. We saw caricatures of this portrait of Manjiro on food packaging, tourist wayfinding information, and toys (which we really need for our museum shop!).

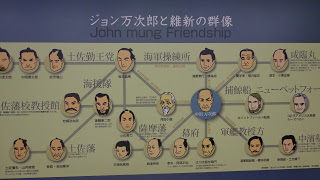

It was fascinating to see how Manjiro’s significance rippled through history and can be felt in places like Usa, Tosashimizu, and Kochi. His legacy is certainly alive and well, and hopefully growing, thanks to exhibitions, research, education, and pop culture representations (toys, games, merchandise, and even an appearance as a character in the popular Japanese TV drama about Ryoma’s life). More on the Rosenbach’s Manjiro manuscript at the Sakamoto Ryoma museum next week!

Very interesting. I would like to know more. How do I access the manuscript?

Hi Grace,

The first step is making a research appointment. You can fill out the form here: https://rosenbach.org/research/make-an-appointment/

Thanks!

The Rosenstaff