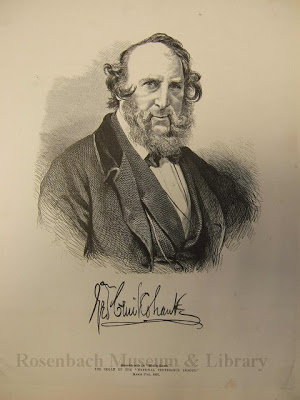

Quick quiz: who is the most-represented illustrator in the Rosenbach collections? If you guessed Maurice Sendak, you are right–our Sendak collections are not fully cataloged, but the number we like to toss around for him is 10,000 books, drawings, and pieces of ephemera. Here’s a slightly harder quiz: who is the second-most-represented illustrator? It is George Cruikshank, clocking in at just about 4000 prints and illustrations (plus more from his father and brother). Believe me, we have a lot of Cruikshank material; several years ago I thought I had finally managed to plow my way through cataloging our entire print collection, only to find out that there were 14 more volumes, containing THOUSANDS of Cruikshank prints lurking in another storage location. But they’re all cataloged now and you can see them for yourself in our

online catalog.

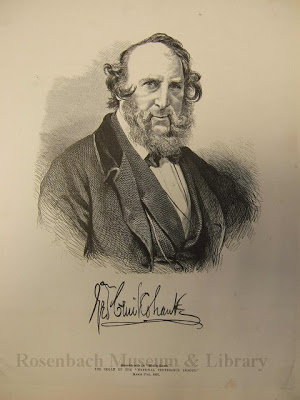

Knight, portrait of George Cruikshank. London, 1865. 1954.426

Knight, portrait of George Cruikshank. London, 1865. 1954.426

Cruikshank has been on my mind recently for a couple of reasons. First, our amazing collections intern Jessica Walthew was working this week on tracking down information on some of our Cruikshank “mystery prints”–piece for which we didn’t have a date or explanatory info. More on her fascinating findings, involving murder and intrigue and royalty, next week. Secondly, our Cruikshank holdings are at the heart of our upcoming

Philagrafika 2010 project; contemporary printmaker

Enrique Chagoya came to the Rosenbach in the fall and made his own piece inspired by Cruikshank. We’ll be displaying Chagoya’s and Cruikshank’s work together as part of a

program February 18-20.

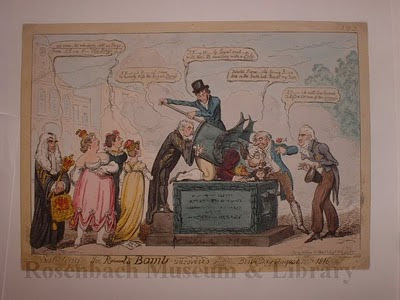

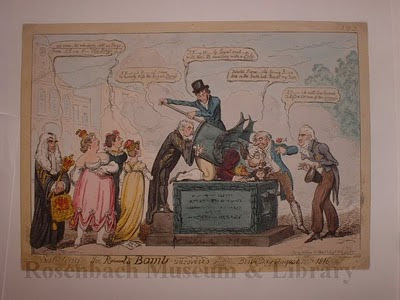

By now, you may be wondering, who the heck is George Cruikshank. He was born in 1792 and was raised in the print-making business. His father, Isaac Cruikshank, was a noted caricaturist and George started out his career in the 1810s doing politically satirical prints, many of which revolve around Napoleon, or around the foppery and incompetency of George IV, who was then serving as regent. (That’s another reason Cruikshank has been on my mind–2010 marks the 200th anniversary of George III being declared insane, which paved the way for the regency, which began in early 1811). In fact, in 1820 Cruikshank actually received a 100 pounds from the crown in exchange for a pledge “not to caricature his Majesty in any immoral situation” Here are a couple of examples of his George IV satires:

George Cruikshank,

Saluting the Regent’s Bomb uncovered on his birth Day…London, 1816. 1954.1880.711

George Cruikshank,

Royal Hobby’s or The Hertfordshire Cock-Horse! London, 1819. 1954.1880.1128

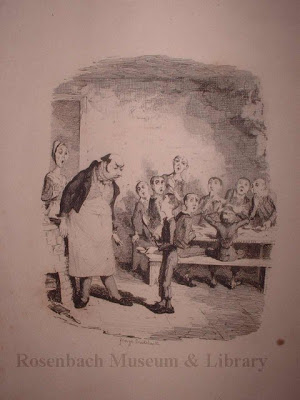

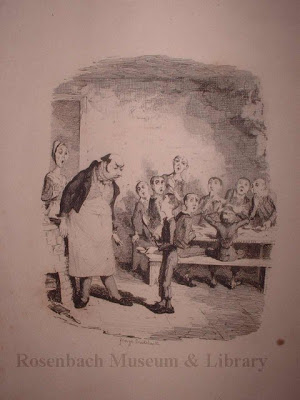

In the 1820s and 1830s the fashion for full-sheet caricatures waned somewhat and Cruikshank turned to book and comic magazine illustrations as his main line of business. His most famous illustrations are undoubtedly those he did for Charles Dickens’s Sketches by Boz and Oliver Twist.

George Cruikshank,

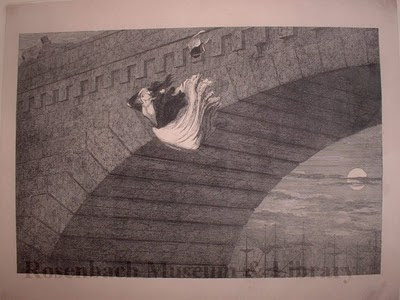

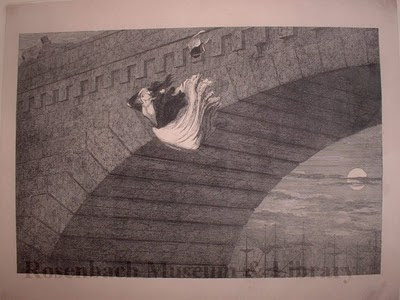

Oliver Asking for More. 1837. 1954.898

In the 1840s Cruikshank became increasingly involved with the temperance movement and his fanaticism somewhat damaged his professional career (including his relationship with Dickens). However he turned his talents towards creating temperance art, including two wonderful series of images entitled The Bottle and The Drunkard’s Children which trace the woes of a family when first the father and then the other family members succumb to dissipation. Many people are rather critical of the artistic merits of his morality tales, but I think some of them are quite striking; take, for example, plate VII of The Drunkard’s Children in which “The Poor Girl, Homeless, Friendless, Deserted, Destitute,and Gin-Mad Commits Self Murder”

George Cruikshank, The Drunkard’s Children: Plate VII. London, 1848. 1954.493

Interestingly, Cruikshank produced these series of prints as glyphographs, which is a fairly uncommon print-making process in which a wax ground is laid down on a metal plate, the design is drawn through the wax, and then an electrotype is made, from which the final prints are produced.

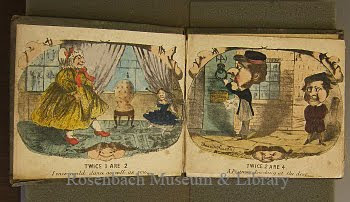

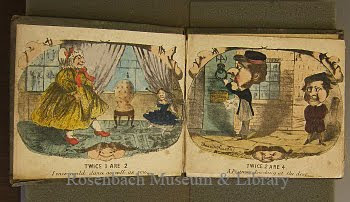

Cruikshank died in 1878 after a long, productive, and illustrious career as a caricaturist, illustrator and printmaker in which he created something on the order of 10,000 images (no, despite our wealth of holdings, we don’t have them all). I’ll end this post with an unusual Cruikshank volume which was donated to us a couple of years back. It’s entitled Comic Multiplication and I haven’t been able to track down any information on this publication (although I know Cruikshank published a Comic Alphabet in 1836). Even more oddly, the illustrations (not the printed text) are printed in reverse, which is clear in illustrations containing words or numbers, and I can’t for the life of me figure out how that happened. If anyone has any answers to this mystery, I’m all ears.

George Cruikshank, Comic Multiplication. Gift of S. Oakley VanderPoel, by his grandson Horace Andrews

George Cruikshank, Comic Multiplication. Gift of S. Oakley VanderPoel, by his grandson Horace Andrews

Knight, portrait of George Cruikshank. London, 1865. 1954.426

Knight, portrait of George Cruikshank. London, 1865. 1954.426 George Cruikshank, Saluting the Regent’s Bomb uncovered on his birth Day…London, 1816. 1954.1880.711

George Cruikshank, Saluting the Regent’s Bomb uncovered on his birth Day…London, 1816. 1954.1880.711

George Cruikshank, Comic Multiplication. Gift of S. Oakley VanderPoel, by his grandson Horace Andrews

George Cruikshank, Comic Multiplication. Gift of S. Oakley VanderPoel, by his grandson Horace Andrews