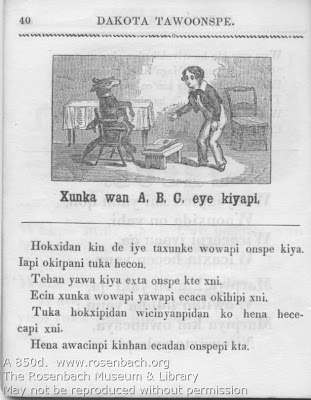

The Dakota language primer shown above contains several woodcut illustrations. Most of them are bucolic, Currier & Ives type jobs — farmers working the fields, bonnetted little girls holding flower baskets in quaint cottage door ways, children sailing on a windy, but not threatening, lake, etc., etc. (Most of them depicting scenes not in the least familiar to the book’s target audience, I suspect.) And then there’s this one:

I hope you can make it out (click on it for a slightly larger version): a dog tied to a chair, wearing dark glasses and a bandana around its neck, with a book and an urgently gesticulating boy in front of him. I guess the boy is teaching the dog the alphabet, but I just find this image weird. Maybe the text explains it all, but I don’t read Dakota, so I have no idea. Given the undeniable tragedies of U.S.-American Indian history, one could use some kind of historically long-distance, foggy, crude cultural studies lens to read the image as an unintentional commentary on teaching Indians to read and write, i.e., it’s like trying to make a beast literate. But I must catch myself before I backslide into the strident political correctness of my younger days and bore you with my critique of the extensive evils of colonialism, real as they may be. (I’m probaly not being fair to the book’s author, Stephen Return Riggs, a missionary who spent forty years living among the Sioux with his wife and nine children (Alfred, Isabella, Martha, Anna, Thomas, Henry, Robert, Cornelia, and Edna) and produced landmarks studies of Dakota language and culture.

As it turns out, precious few people can speak Dakota (a.ka. Santee — a dialect of the Siouan languages related to Lakota) nowadays, somewhere between 8000 to 9000 at all levels of fluency. Those who do speak the language are growing older (average age is 65) and aren’t being replaced by younger speakers. So the language is on the verge of extinction. Much more information of on its precarious status can be found here.

The death of a language must be very sad thing, indeed. I imagine there’s a way in which languages embody a certain understanding of the world. Yiddish nearly went extinct after the Holocaust, for example, and having recently acquired a copy of Leo Rosten’s The Joys of Yiddish (after hearing legendary Philadelphia drummer Elaine Hoffman Watts jokingly refer to her piano player as a shlepper), I have to say  it’s hard to imagine American English without the contributions of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim. (Bagel? Hooha? Schmegegge? Schmuck? Shtick? Nogoodnik? All from Yiddish.) And here we’re just talking about vocabulary words, let alone the other multifarious contributions Yiddish speakers have made to our culture. Perhaps the Dakota language’s influence has not been felt quite as widely (Minnesota takes its name from the Dakota language), but that’s no reason to ignore its peril. As the Lakota Language Consortium puts it, “each nation uses language to embed ideas of culture, history, philosophy and belief. Language is ultimately the core expression of a people’s existence.” You’d have to be pretty hard-hearted not to see that as a loss to humanity.

it’s hard to imagine American English without the contributions of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim. (Bagel? Hooha? Schmegegge? Schmuck? Shtick? Nogoodnik? All from Yiddish.) And here we’re just talking about vocabulary words, let alone the other multifarious contributions Yiddish speakers have made to our culture. Perhaps the Dakota language’s influence has not been felt quite as widely (Minnesota takes its name from the Dakota language), but that’s no reason to ignore its peril. As the Lakota Language Consortium puts it, “each nation uses language to embed ideas of culture, history, philosophy and belief. Language is ultimately the core expression of a people’s existence.” You’d have to be pretty hard-hearted not to see that as a loss to humanity.

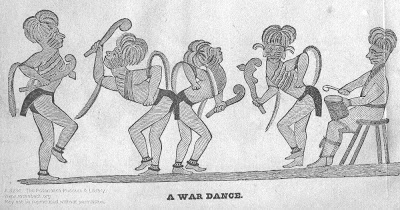

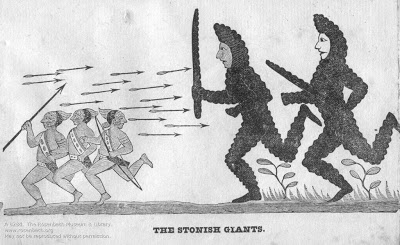

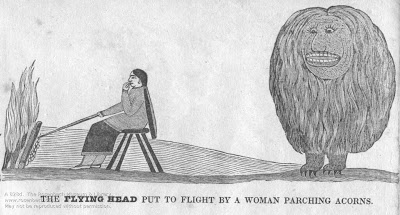

Anyway, the Rosenbach has quite a few American Indian language primers, including a few others in Dakota, and other books about Indians. I’m not sure how useful the primers would be to folks looking to revive a dying language, I’m sure they are many, many interesting and compelling stories connected to them. These illustrations come from David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations…, possibly the first English-language Indian history written by an Indian. Yeah, they’re primitive and kind of humorous, but it’s hard not to be fascinated by them. It’s hard not to ask what the stories behind them are, to want to know about the people who created them:

And, according to Wikipedia, there’s some thinking that this book may have influenced the Book of Mormon. If so, that makes it all the more interesting. Origins of the Book of Mormon aside, I think you get my point.

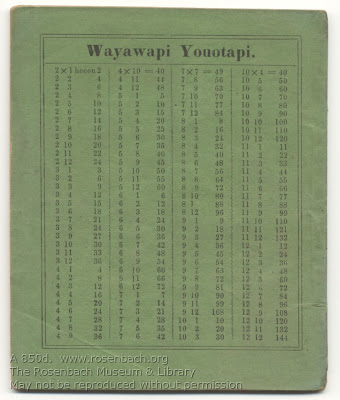

Click here to learn the parts of the body in Dakota. Here for a couple Dakota folktales. And from the book we started with, here are your multiplication tables in Dakota:

Images:

1.2. Stephen Return Riggs (1812-1883). Dakota Tawoonspe. Woapi II. Dakota Lessons. Book II. Lousiville, Ky.: Morton and Griswold, [1850.] A 850d

3. Leo Rosten (1908-1997). The Joys of Yiddish. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968. MML 1196

4, 5, 6. David Cusick (c.1780-c.1840). David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations… Tuscarora Village, Lewiston, Niagra Co., [Lockport. N.Y. Cooley & Lothrop, printers] 1828. A 828d

7. Stephen Return Riggs (1812-1883). Dakota Tawoonspe. Woapi II. Dakota Lessons. Book II. Louisville, Ky.: Morton and Griswold, [1850.] A 850d

Hello,

I stumbled upon this blog in a Web search for Dakota language educational materials. You are correct in that there are very few people who speak Santee Dakota. I have been learning Dakota for about seven years now. It is taught at the University of Minnesota by a very good teacher, a Dakota man who is a second-language learner of Dakota himself. His father is Dakota, whose parents spoke the language, but his father was sent to a boarding school and now can remember only a little bit of the language.

I am not Dakota myself but I love the language and am committed to doing what I can to maintain and revitalize it. Currently that means pursuing a PhD in Applied Linguistics and Technology at Iowa State University, where I intend to develop more electronic and multimedia learning resources for Dakota. At the University of Minnesota I helped construct a course website for Dakota–the first of its kind, wrote a small handbook on verbs, and have taught the Dakota language in community classes for several years. I wrote one of my M.A. theses on issues of Dakota pedagogy (ironically, it was for a Master’s degree in Teaching English as a Second Language), and my other M.A. (in U.S. History) on Dakota history in Minnesota. I have been interested, too, in the pedagogical materials created by missionaries like Riggs and Williamson to teach reading and writing to the Dakota people in the 19th and 20th centuries, and I have studied the various writing systems they employed to write Dakota.

For example, two characters employed by the brothers Gideon and Samuel Pond, who were among the first white men to live with the Dakotas and learn their language systematically, were X and R. The r sound does not exist in Dakota. In fact, when they first began learning English, they had trouble pronouncing it. I don’t see any examples of that sound in your scanned page. R was used to represent a gutteral h, similar to the final sound in the German Bach, or Scottish loch. The X was used to represent the sound which, in English, is normally written sh. Thus, in that system “English” would be written “Englix.” This has caused no end of confusion among historians and others, who did not understand how X and R were being used in that context. At some point in the second half of the 19th century, probably 1860s or ‘70s, the x came to be written as ṡ (or ś) (an s with a dot over it) and the r came to be written as ḣ (h with a dot over it). But not everybody was informed of the update. People who were taught the r/x way in the 1840s continued to use it throughout their lives. In some cases, Dakota names got stuck that way, such that we have “Marpiya Wicaxta,” which should be written Maḣpiya Wicaṡta (Mahpiya Wicasta), but many historians don’t know any better. Sadly, there are Dakota people today who don’t even know their own names. I met a man once whose family name was Marpiya, and he pronounced the r and had no idea that it should be otherwise.

Those missionaries are an interesting lot, in my view. On the one hand, they were of course trying to convert the Dakota to Christianity, to CHANGE them in a way they had no right to do. On the other hand, they took the effort to learn the Dakotas’ own language, and took the approach that if you’re going to try and teach someone to read and write, it’s a heckuva lot easier to do it in their native language first (Dakota), without trying to introduce a foreign language at the same time (English). That is why, today, there are so many schoolbooks and pedagogical materials IN THE DAKOTA LANGUAGE. Granted, they’re heavily biased, to the point of being ridiculous (as in the page above), but they’re in Dakota, which is not to be sneezed at when some indigenous languages have scanty or no documentation whatsoever.

My interpretation of the text is:

[Picture caption]: “A dog is being made to says the ABCs;

“This boy himself is [trying to] teaching his dog book learning. It’s incapable of speech, but he’s doing it.

“Even though he subjects it to reading for a long time, it will not learn.

“After all, dogs cannot read at all.

“But little boys and girls are not [dogs].

“If they try, they will soon learn.”

What strikes me most about this is the language used for “teaching” the dog. There are different ways in Dakota to indicate that something is causing or having an effect on something else. The form used here, -kiyapi (-kiya) implies that there is some kind of force or outside agency involved:

eye kiyapi: making it say

onspe kiya: make it learn

yawa kiya: make it read

For example there are two ways I could say (in Dakota) “He made me smile.”

1. The normal way, like he said something that made me smile, or

2. The not-normal way, like he made/forced me to smile by holding a gun to my head and saying “SMILE or I’ll blow your brains out!”

I haven’t done a huge amount of linguistic research into the causative affixes in terms of their collocations; I’m sure there are some published studies out there. But that’s what I’ve picked up in seven years of learning Dakota as a speaker and teacher.