Before we dive into this week’s blog post, first a big thank you to everyone who attended or assisted with this year’s Bloomsday. Also, a big thank you to the weather gods–can we order up another picture-perfect day for next year, please? We considered writing a Bloomsday wrap-up post for the blog this week, but we couldn’t do better than Frank Delaney’s lovely tribute, so just go read his.

Instead, we offer another trip through the collections with our intrepid intern Anna Juliar

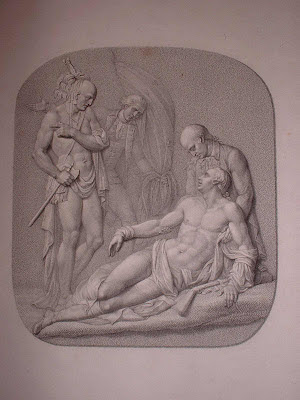

storage a few weeks ago, I found a print that looked very familiar to me:

|

|

Luigi Schiavonneti, after intaglio gem by Nathaniel Marchant,

The Death of General Wolfe. c. 1790-1810, stipple engraving. Rosenbach Museum & Library, 1954.1591 |

James Wolfe. The only reason I knew this immediately is that it is derived from

the very famous painting The Death of

General Wolfe by Benjamin West, which can be found in nearly all art

history text books. Benjamin West actually painted quite a few versions of this

painting, but the original is at the National Gallery of Canada.

The story behind the painting goes as follows:

Indian War, the British General James Wolfe suffered a mortal wound. He lay

dying, surrounded by his officers, as news broke that his army had won the

battle. His courageous victory and death secured a place for him as a martyr in

the pantheon of British war heroes.

his own fame as the preeminent painter of the 18th century with his

painting The Death of General Wolfe. In his moving portrayal of Wolfe’s last moments,

West painted a Christ-like General Wolfe expiring before his trusted comrades,

who look on in various expressions of grief. The painting was exhibited in the

1771 Royal Academy exhibition in London, and is now in the collection of the National

Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. The painting was an immediate success, and is often

used by teachers and scholars as the epitome of grand history painting in the Neoclassical

style.

to research the lesser-known second life of this iconic image. The image’s true

claim to fame, in fact, was actually the immense popularity of prints produced

after the painting. Only a year after the painting was exhibited, the

enterprising publisher John Boydell signed an agreement with engravers William

Woollett and William Ryland to publish a print after the painting, along with a

key that identified six of the men in the foreground, in cooperation with West.

Finished in 1776, it was an instant success. Woollett’s engravings netted a

spectacular profit of over 15,000 pounds by 1790. This print was truly

England’s first widely successful reproductive print:

|

|

William Woollett, The Death of General Wolfe. engraving. 1776

Library of

Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs |

Prints after this painting generated a completely

new popular taste and market for historical pictures. Middle class people could

purchase them to hang in their parlors and sitting rooms, while shops, inns,

and restaurants displayed them on the walls. Prints after West’s composition

traveled to France, Germany, and America. While Woollett continued to pull

prints from the original plate for a long time, many other copies and

interpretations (including counterfeit prints) sprang up in England and abroad.

The Death of General Wolfe graced

needlepoints, teapots,

trays, ceramic ware,

and carved gems.

Revolutionary War. In fact, both the British and Americans used the scene to

support their own causes! Each side felt that Wolfe would have supported their

own causes, if he were still alive.

|

| Luigi Schiavonneti, after intaglio gem by Nathaniel Marchant, The Death of General Wolfe. c. 1790-1810, stipple engraving. Rosenbach Museum & Library, 1954.1591 |

Marchant, a well-known gem carver, to create an intaglio depicting the death of

General Wolfe. The gem was then reproduced by the engraver Luigi Schiavonetti.

Because he typically re-created scenes from Classical antiquity, Marchant took

generous artistic license and crafted a scaled-down version of the foreground

scene in West’s painting. He depicted the heroic general shirtless, muscular,

and much more conscious than the Wolfe of West’s painting. He moved the Native

American figure from the outskirts of West’s scene to the foreground of the

composition. Similarly muscular and draped in a swathe of fabric, the Native

American points to the left, like the soldier behind him, locking eyes with the

General to indicate Wolfe’s victory in death.

another version of the scene:

|

|

George B. Ellis, engraved title page for The History of England by Tobias Smollet. Philadelphia: M. Polock, 1854. Rosenbach Museum & Library, 1954.1591

|

Smollett, George B. Ellis engraved his own version of the famous image.

Enclosing the central scene of Wolfe’s death within an elaborate gothic frame,

Ellis remained faithful to many of the compositional elements by simply

cropping the picture’s left half. The kneeling Native American to the left

barely made the cut, and Ellis simplified the composition by eliminated the

battle raging behind the scene and including a swirling mass of smoke behind

the flag. Credit is still given to Benjamin West in a tiny tag line to the

bottom left of the image.