This blog post was written by Andrew White

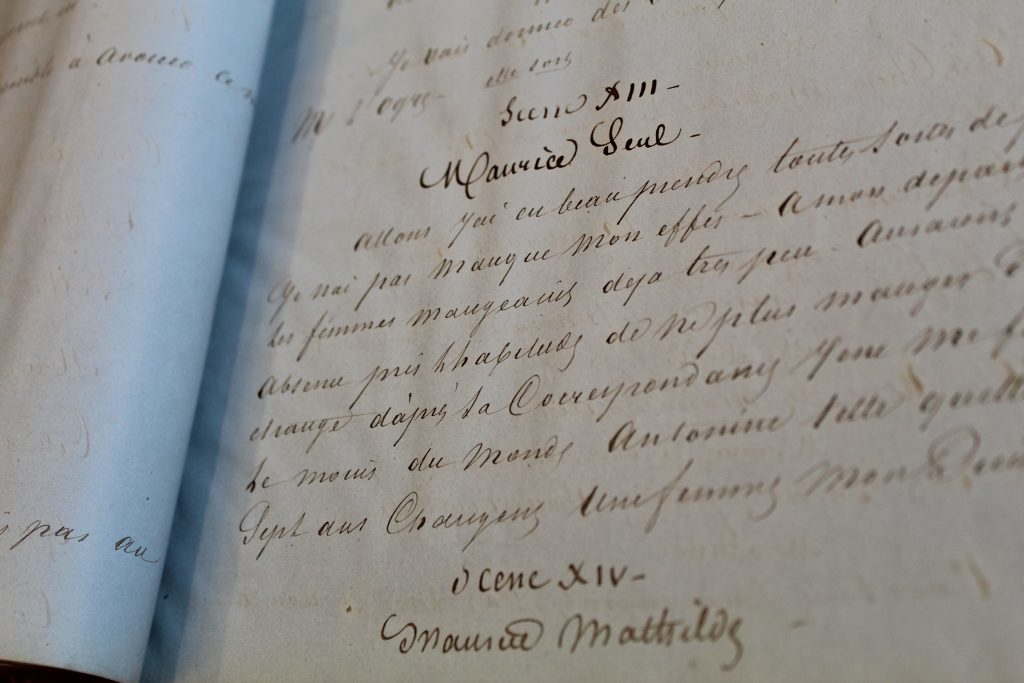

Alexandre Dumas’s father was one of Napoleon’s generals, nicknamed “Hercules” by the emperor, and “Black Devil” by France’s enemies; Dumas’s surname came from a paternal grandmother, Marie-Cessette Dumas, an Afro-Caribbean woman held in slavery on what is now Haiti. In his career as a writer, the colossally prolific Dumas used different colored paper for each genre he explored, but never white. At The Rosenbach, Dumas is represented by two bound manuscripts, both on the blue paper he used for fiction. One, Blanche de Neige, is a retelling of Snow White from a book of fairy tales, Contes pour Les Grands et les Petits Enfants; the other is a one-act play, L’Invitation a la Valse, which Dumas wrote to pass lonely hours in England while covering the elections of 1857. (The “Illustrated London News” hoped the French visitor had “already composed, beside his letters to the Presse, several startling novels founded upon election intrigue!”)

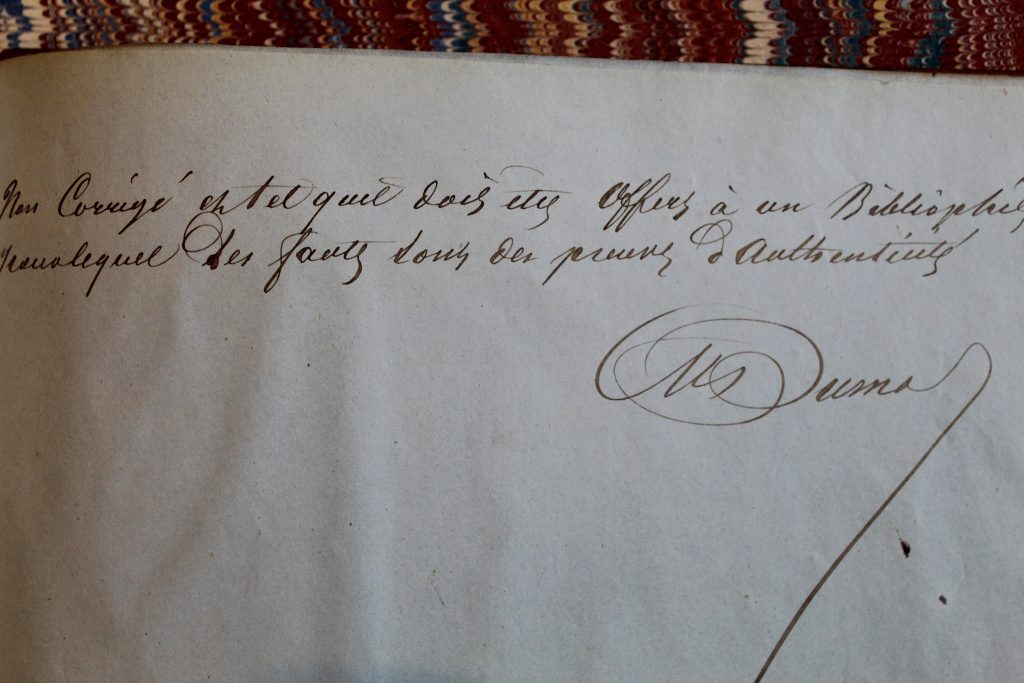

Below, see Dumas’s droll envoi to his L’Invitation manuscript:

“Not corrected, and in such state as it must be offered to a bibliophile, to whom faults are proofs of authenticity. Alex. Dumas.” As you see, L’Invitation a la Valse is written on the—now faded—blue paper Dumas used for fiction. The play was written as a vehicle for a much-younger mistress, actress Isabelle Constans, to whom Dumas pledged “No woman… will have such parts to perform as I will write for you over the next three years,” perhaps intuiting that Constans might not live much beyond that. In his biography of Dumas, F.W.J. Hemmings airily describes Constans as “a fair-haired, gently mannered girl, doomed in all probability to an early death from a wasting disease.”

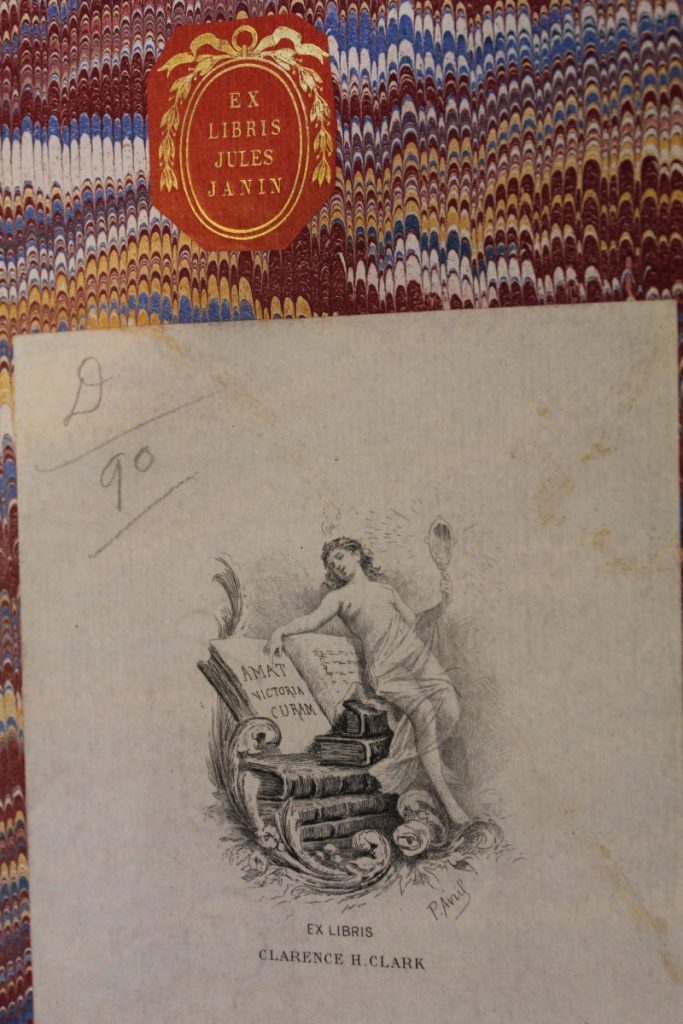

Whether Constans sold the manuscript, or consumption tugged it from her pale hands, L’Invitation a la Valse came into the possession of Jules Janin, a critic and book collector Dumas once challenged to a duel over a bad review (though the two men, each a year to the other side of forty at the time, reconciled before blood was shed). Below, see Janin’s bookplate on the front endpaper of the L’Invitation a la Valse binding:

And below it, the bookplate of Clarence H. Clark, the Philadelphia banker, developer, and book collector for whom West Philly’s Clark Park is named! (In addition to being the previous owner of a Rosenbach manuscript, Clark contributed to the collections of another Philadelphia cultural institution, the Academy of Natural Sciences, as this article on the Academy’s site will attest.)

About Dumas: After a youthful attempt to assassinate God was thwarted by his baffled mother, the adult Alexandre wrote over 600 books and succeeded—or so he believed—at curing himself of cholera with a wine glass full of ether. (The Rosenbach discourages readers from attempting this experiment at home.) If these feats failed to win him enduring fame, classics like The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Christo assure Dumas’s literary immortality, which was achieved in the face of lifelong racist stereotyping. In his autobiography (Volume IV), Dumas wrote of the lens through which his generation viewed him: “I had the passions of the African, they said, and they pointed to my frizzy hair and dark complexion, which neither could nor would deny its tropical origin.” Even when praising him, contemporaries fixated on Dumas’s ethnicity. “Negro by origin and French by birth,” read an 1834 profile, “he has light even in his most fiery ardors; his blood is made of lava; his thinking is a spark.”

The obsession of Dumas’s contemporaries on his African heritage died with them, to be replaced by a century of erasure. Half of those informally surveyed by the author of this blogpost attest that they had no idea of Dumas’s color growing up. As the great James Baldwin said in a 1970 interview, “I was thirty before I understood… that Alexandre Dumas wasn’t fully white—but they don’t teach us that in American schools.” Dr. Rosenbach’s two Dumas manuscripts reside in his library’s Continental Literature section, in the territory occupied by France. We are proud to have them, and proud that this dynamo of literature, as accomplished in letters as his Herculean father was on the battle field, is represented in color at the Rosenbach.

Thank you for covering Dumas’ African heritage AND the erasure of that heritage. It’s important for people to understand that our world is incredibly more diverse than any of us have been taught.