– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

A fascinating book within the collection of the Rosenbach, Homes of the American Statesmen, written in 1854, explores the various homes of men from our country’s early history. The book’s publishers wished “to preserve, in living memory, the individual and private memories of the benefactors of our country.”

|

| Homes of American Statesmen: with Anecdotal, Personal, and Descriptive Sketches. New York: G.P. Putnam and Co., 1854. Rosenbach Museum & Library. A 854h. |

Each chapter highlights a different man; the first and longest chapter focuses on George Washington, while later chapters illustrate the homes of Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, Andrew Jackson, and many more. Each chapter includes beautiful wood engravings of their homes (some chapters have more than others; the most plentiful being the chapter on Washington) as well as brief histories of the men and a facsimile of a letter written in each of their hands.

Possibly the most fascinating chapter is that of George Washington written by Mrs. C.M. Kirkland. This chapter has the advantage of telling the history of both Washington’s adult life and also of the Revolutionary War itself through the various headquarters in which he stayed. Although there are quite a few wood engravings within the chapter, I decided to show those that pertain to the war in and around Philadelphia. All of these houses are still extant so it gives us an opportunity to see how they look today and how they may have been preserved as monuments of our past.

On the eve of the Battle of Brandywine (September 11, 1777), Washington established his headquarters at the house of Benjamin Ring, a Quaker farmer and miller, in what is now Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania.

|

| Wood engraving of the headquarters of Washington at Chadd’s Ford, Homes of American Statesmen: with Anecdotal, Personal, and Descriptive Sketches. New York: G.P. Putnam and Co., 1854. A 854h.” |

|

||

| Benjamin Ring House, now now part of the Brandywine Battlefield Historic Site. Photo by road_less_trvled. |

After losing the Battle of Brandywine, Washington’s troops retreated and eventually made their way to Germantown after the British capture of Philadelphia. After an unsuccessful battle in Germantown, Washington retreated to White Marsh where he stayed from November 2-December 11, 1777. He successfully fought off attack from the British on December 5th and 6th but relocated to Valley Forge on December 11th for the duration of the winter.

Below is an image of Washington’s headquarters in White Marsh, now in Springfield, owned by George Emlen at the time, along with a modern image.

|

| Wood engraving of the headquarters of Washington at White Marsh, Homes of American Statesmen: with Anecdotal, Personal, and Descriptive Sketches. New York: G.P. Putnam and Co., 1854. A 854h. |

As I mentioned above, Washington and his troops moved to Valley Forge where the Continental Army suffered through a brutal winter with food shortages and inadequate shelter and clothing, killing nearly 2,500 American soldiers from December 1777 to February 1778. During this period, Washington stayed in the home of Isaac Potts, which was being rented by his relative, Deborah Hewes, who in turn rented the home to Washington. The house was located at the confluence of Valley Creek with the Schuylkill River in Valley Forge, PA.

|

| Wood engraving of Isaac Potts House at Valley Forge, Homes of American Statesmen: with Anecdotal, Personal, and Descriptive Sketches. New York: G.P. Putnam and Co., 1854. A 854h |

|

| Modern image of the Isaac Potts House in Valley Forge, now part of the Valley Forge National Historic Park, image from National Park Service |

|

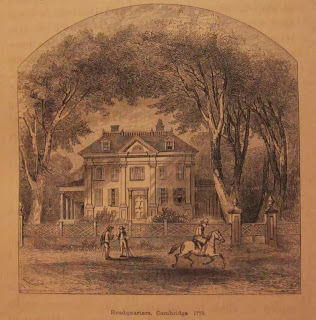

| Wood engraving of the headquarters of Washington in Cambridge, MA, Homes of American Statesmen: with Anecdotal, Personal, and Descriptive Sketches. New York: G.P. Putnam and Co., 1854. A 854h |

|

| Longfellow House,now the site of the Longfellow National Historic Site. Image from National Park Service Digital Image Archive |

While these wood engravings may be my favorite part about this book, another very interesting and unique feature can be seen inside the front cover of the book, an original crystallotype photograph (a process patented by this photographer in 1850) of the John Hancock house in Boston. Although the handwritten notation (as well as its reference in the publisher’s note) indicate that it is a sun picture, this may just be the name given to early photographs. Each copy of the first published edition had an original photograph pasted into the book as a frontispiece. The problem of press printing of photographs remained unsolved until the 1880s when the cross-line screen was introduced, diffusing the photographic image into patterns of dots which could then be printed by letterpress.

|

| Crystallotype photograph of the John Hancock House, Homes of American Statesmen: with Anecdotal, Personal, and Descriptive Sketches. New York: G.P. Putnam and Co., 1854. A 854h.” |

Nowadays it is hard to find the old houses. Very curious and interesting post with the matching of current houses with those present in the book. Looking forward to know more about this book.

Wood Deck Care