The Miriam-Webster dictionary defines Manumission as ‘formal emancipation from slavery’ (note that The Rosenbach has two first editions of Noah Webster’s landmark Webster’s Dictionary!). Manumission was one vehicle that enslaved Africans leveraged to gain their freedom. Slave laws made manumission difficult, however, requiring large sums to legally manumit slaves.

Here at The Rosenbach we have fascinating insight into an unusual manumission story; one that hints of love across social boundaries, and has ties directly to our founding mother, Martha Washington. Martha was a widow when she met George in her mid-20s. Her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis died at a young age. Daniel Parke Custis was the son of John Custis IV, a politician and a member of the Governor’s Council of Virginia.

John Custis was not a happily married man. He often said that the only happy periods in his life were at his Eastern Shore estate, where he would spend time away from his wife. This was an open secret in Virginia society. Another open secret was that John Custis had another son whom he fathered with his enslaved African servant Alice.

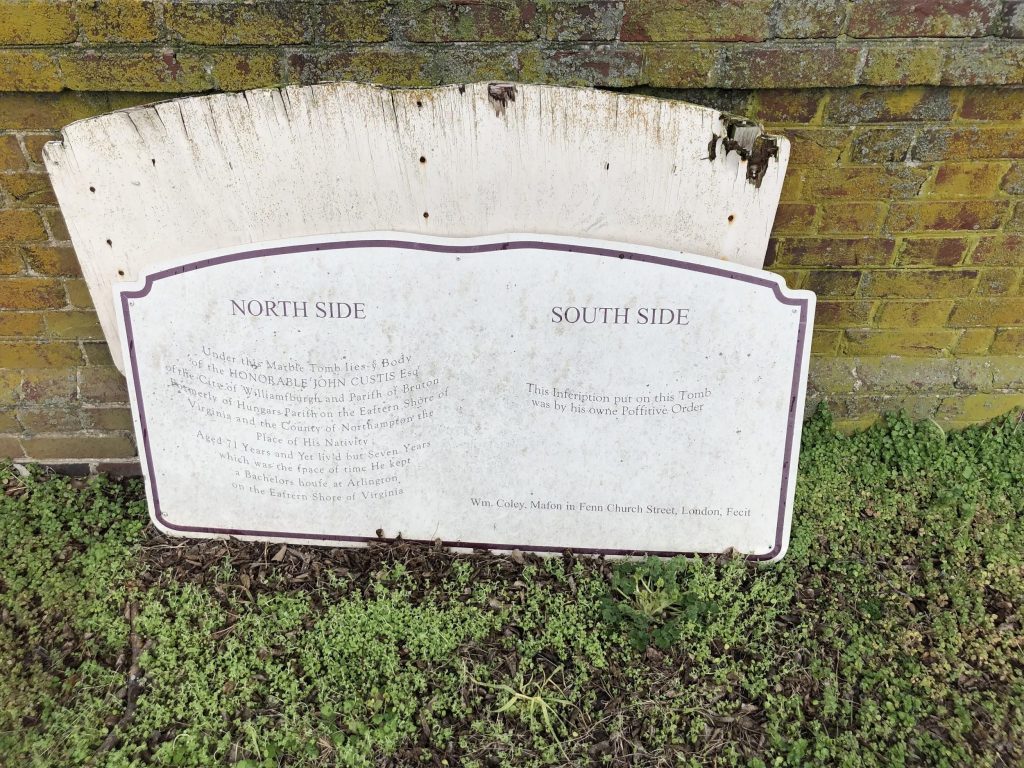

John Custis named his enslaved son John; he was also known as Jack. And Jack was well loved by John Custis. When Custis realized he was dying, he did two things. First, he made Daniel Parke Custis promise (on threat of disinheritance) that he would be buried at his Eastern Shore estate and that these words would be engraved on his tombstone:

“Yet lived but Seven years

which was the Space of time

he kept a Batchelors House at Arlington on the Eastern Shoar of Virginia.

This Inscription put on this Stone by his own positive Orders.”

In other words, John Custis felt that he only lived when he was a ‘Batchelor’ at his Eastern Shore estate. John Custis was never divorced, so he was never legally a bachelor. Here he makes references to a temporary period of reprieve where he must have felt like a bachelor, or free from his unhappy marriage, when he was living by himself. That he would go to this length to indicate his unhappiness with his married life is unusual and startling for this time period.

The inscription is worn and barely visible on the tombstone today, but is written on a nearby sign for visitors to see.

Second, and most importantly, he arranged for the freedom of Jack, Alice, and all of Jack’s brothers and sisters. Jack’s manumission also included the inheritance of a house, slaves, and a promise from Daniel Parke Custis to take care of him. Daniel Parke Custis did take care of Jack, and for a short period after his marriage to Martha, Martha served as Jack’s step-mother. Sadly, Jack passed away of an illness at age 12.

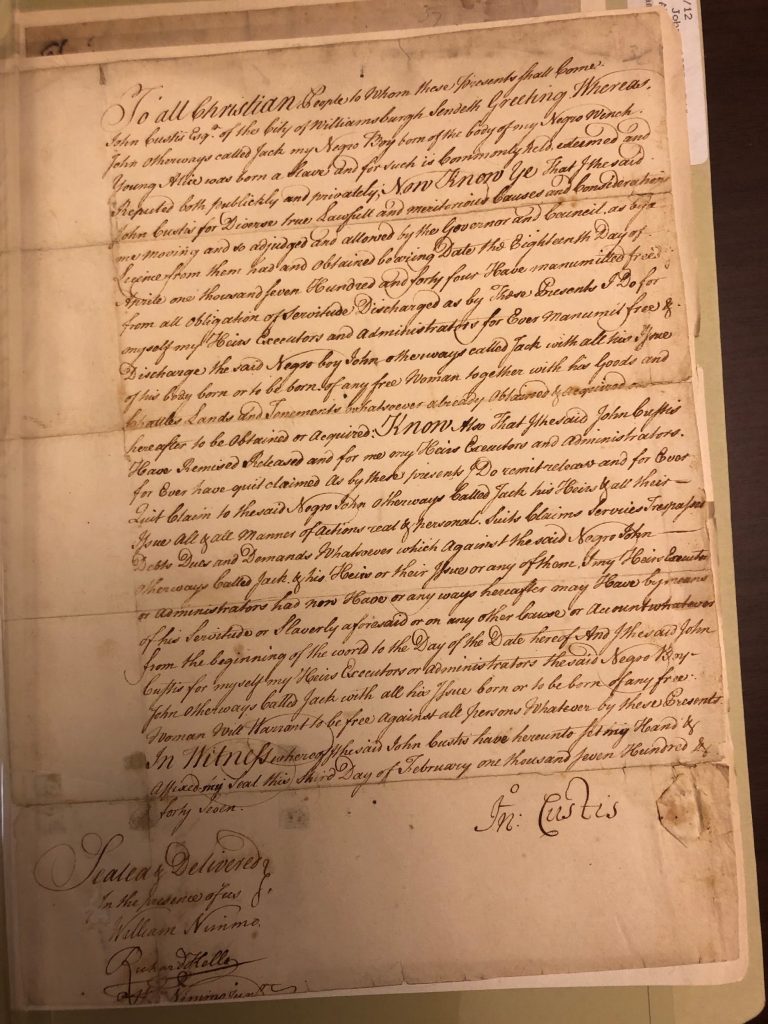

Here is the Rosenbach’s manumission paper dated April 18, 1744, where John Custis frees Jack and provides for him after his passing. He writes “I forever, manumit, free the said Negro Boy John:”

We can ponder the life of John Custis IV. Was he in love with Alice, John’s mother? Why was he so miserable in his marriage that he left a testament to his misery for all the world to see? We can also think of the blended family of Daniel Parke Custis, Martha Dandridge, and John as similar to a modern American family of today, multicultural and multi-dimensional. And finally, we can think of the boy John “Jack” Custis as a well off, well cared for, and happy African-American boy; an unusual and happy vision for 1744.