Maurice

Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are turned 50 this week (November 20 to

be precise)–that’s 50 years of rumpuses; of successive printings and translations;

of adaptations in art, opera, and film; and of multiple generations finding

some connection that keeps them reading, looking, and passing it on. Such

longevity is a remarkable achievement for any picture book, but while other commemorations have focused on the novelty of the

book’s storyline or the potentially frightening appearance of Sendak’s

monsters, I thought it might be fun to revisit Sendak’s manuscripts (written

during the spring and summer of 1963) and look at some of the transformations

Max and the Wild Things underwent before the book was published. There

are around 40 drafts of the story and Sendak left much on the cutting room

floor in order to condense his tale into the 338 words we know today. In

fact, the book’s most famous scene–the “wild rumpus”–is a case

study in just how carefully Sendak constructed his text in order to create a

convincing allegory.

Many

readers find the “wild rumpus” so powerful because of its very lack

of words in the printed book–it’s a scene anyone can imagine themselves into,

giving way to the primal fantasy depicted. But Sendak’s early manuscripts

conceived a more specific purpose: he used it as a “teachable

moment,” where either the Wild Things taught Max how to do something or

Max schooled the Wild Things. In one version from May 7, the Wild Things

“taught him how to fly by moonlight and ride on the back of the biggest

fish in the sea and how to call long distance and dance to the music of the

wind in the tree.” Revising this slightly, on May 10 Sendak wrote, “…and

taught him many new wild ways: how to frighten the moon into a cloud—how to

catch shadows in the dark forest—how to dance until night was scared into

day…” Vestiges of these lessons can still be seen in the pictures

for the “rumpus,” where the Wild Things and Max howl at the moon, for

example. Ultimately, a teacher-student relationship wasn’t satisfactory

to Sendak’s sense of his characters. Sendak needed Max to become a

Wild Thing, and their romp needed to seem instinctual and cathartic

rather than pedantic. But even after stripping away descriptions of the

“new wild ways” that Max and the Wild Things perform in their escapades,

Sendak needed the right word to kick it off–so where did the word

“rumpus” come from?

|

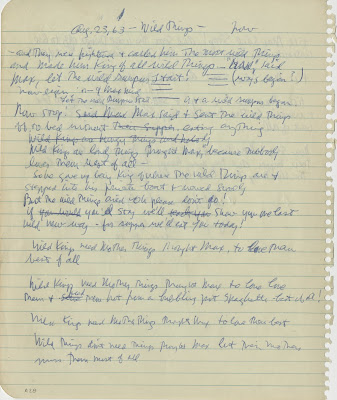

| Manuscript page for Where the Wild Things Are. August 23, 1963. Pen and ink. © 1963 by Maurice Sendak. Used with permission of the Estate of Maurice Sendak. |

This

manuscript page from August 23 is the first mention of it–you can see it on

display in our anniversary exhibition The Night Max Wore His Wolf Suit.

With a slight amount of hesitation, Sendak wrote, “‘Now,’ said Max, let

the wild rumpus start!–(ways begin?)” According to children’s book

historian Philip Nel the word came as a suggestion from Crockett

Johnson, author and illustrator of Harold & the Purple Crayon and

husband of Sendak’s longtime collaborator, Ruth Krauss.

“Rumpus” stuck. It captured the essence of Sendak’s drawings,

sounding just the right note of unruliness without being too specific.

Just

days after this vital word fell into place, Sendak phoned the offices of his

longtime publisher, Harper & Row (now HarperCollins) and dictated the story

to a typist. His editor and mentor was the remarkable Ursula Nordstrom,

responsible for editing so many children’s classics including Charlotte’s

Web, Where the Sidewalk Ends, and Goodnight Moon, along with

books by Sendak, Krauss, and Johnson. Nordstrom returned the typescript

to Sendak to proofread, adding a note at the top (and joking with him about the

typo concerning his name), “Maurice, or Max, or whoever you are–this is

going to be a magnificent, permanent, perfect book” (oh, and next

to “wild rumpus” she also glossed, “Marvelous!”).

Fifty years later Nordstrom is still right.

|

| Typescript for Where the Wild Things Are, August 26, 1963 |

Patrick Rodgers is Curator of the Maurice Sendak Collection at the Rosenbach Museum & Library.