2016 marks the 400th anniversary of the deaths of both William Shakespeare (whose 450th birthday we celebrated two years ago) and Miguel de Cervantes. Traditionally it has been claimed that both men died on the same date: April 23, 1616, but modern scholars have thrown a wrench into the works by suggesting that Cervantes probably died on the 22nd (his funeral was on the 23d) and reminding us that Shakespeare’s death date is itself only inferred from his funeral date on the 25th. Of course, even if they had both died on April 23d, it wouldn’t have been the same day, since England was still on the Julian calendar, while Spain was on the Gregorian, so April 23 in the two nations was ten days apart. (By the way, for those of you keeping score at home, William Wordsworth also died on April 23–many years later, of course)

Cervantes and Shakespeare lived during the birth of the modern world, when their nations were in constant conflict as Spain began to decline and England to rise as world powers. Despite the conflict, flourishing new developments in art and literature crossed borders. Don Quixote was known in Shakespeare’s England, and Dr. Rosenbach wrote his dissertation on some of its influences there. Both writers were among his favorites and well-represented in our collections.

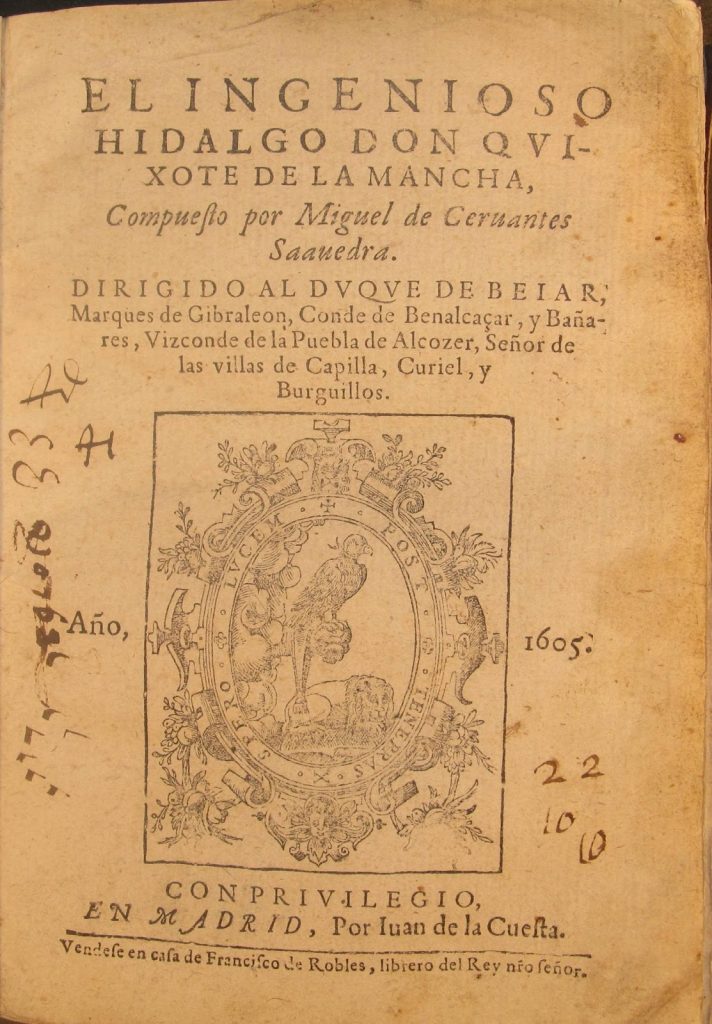

This first edition of the first part of Don Quixote is one of only 18 copies known to survive today. Most of the 400 that were printed were sent to the Spanish colonies in the New World, and some of those were lost in shipwrecks on the way. The book was popular enough in Spain to have four more editions within the year, and another five by the time the second part was published in 1615.

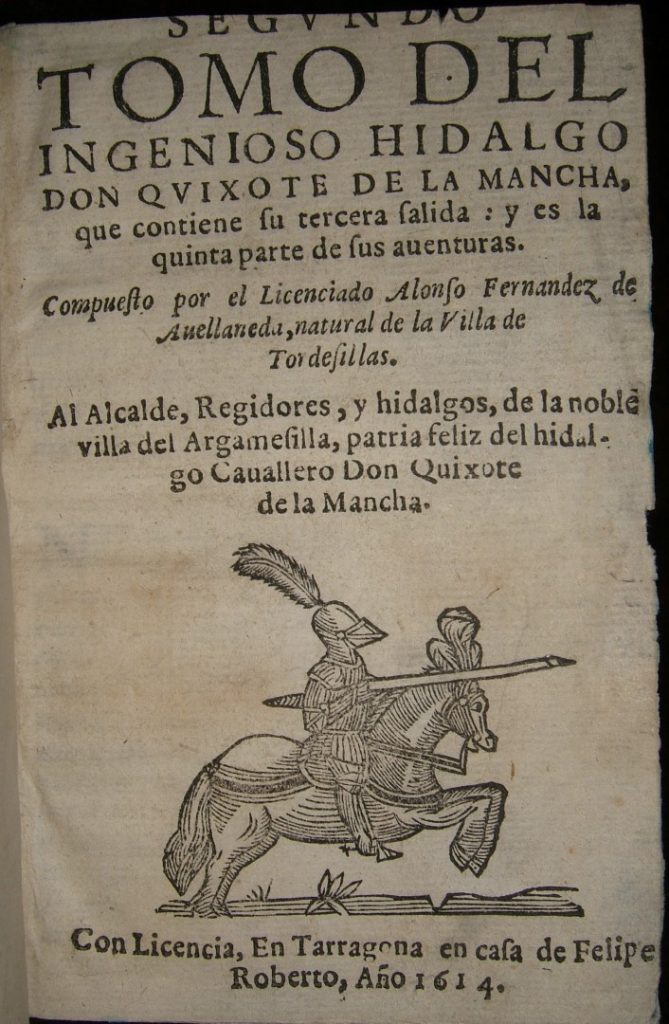

The first part of Don Quixote ended with the promise of a second part, but Cervantes did not finish it until 1615. Meanwhile, a writer calling himself Alonso Fernandez de Avellaneda (his real identity remains unknown) obliged impatient readers with his own continuation. Interestingly enough, although he appropriated Cervantes’s characters, he did not pretend it was the work of Cervantes; in fact the book contains a number of unfavorable references to the original author.

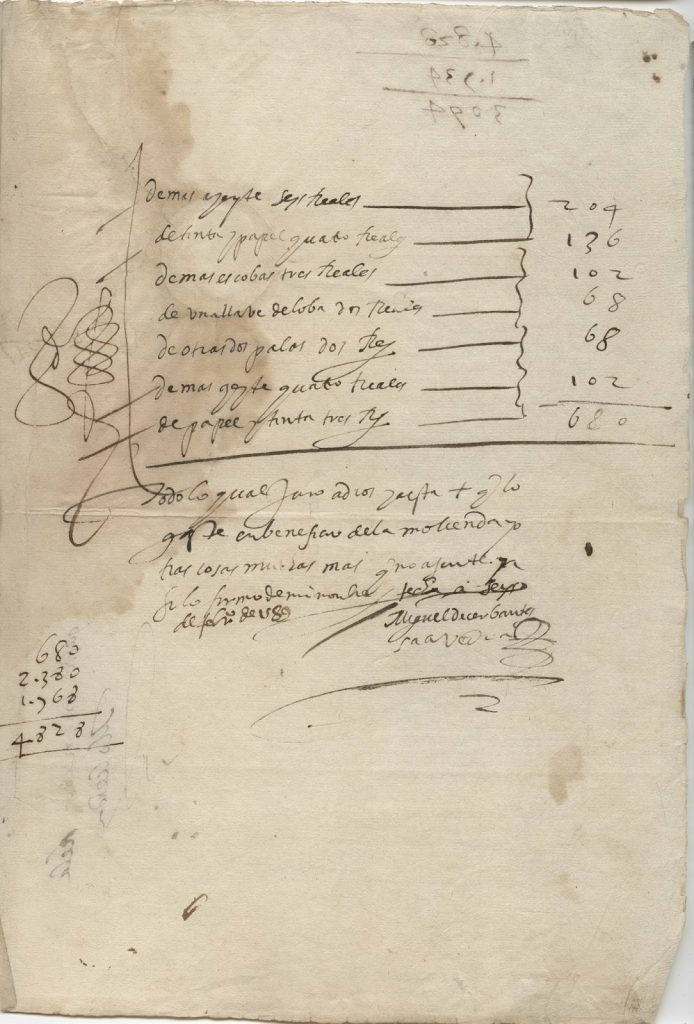

The Rosenbach owns the only three documents in Cervantes’s own hand in the Western hemisphere, all relating to his work as a commissioner of supplies for the Spanish fleet. Communities did not always want to produce the grain they were required to provide, and Cervantes was imprisoned twice for discrepancies in his accounts. This is a report of expenses incurred in 1588–1589 for a mill owned by his supervisor, Antonio de Guevara.

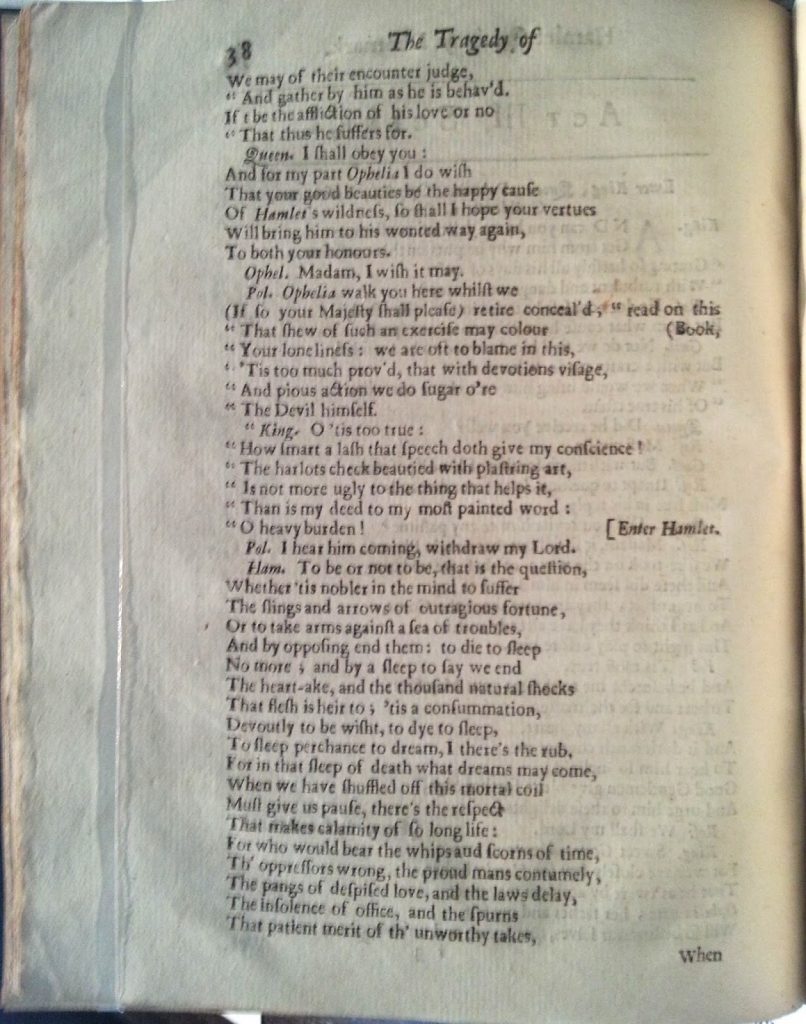

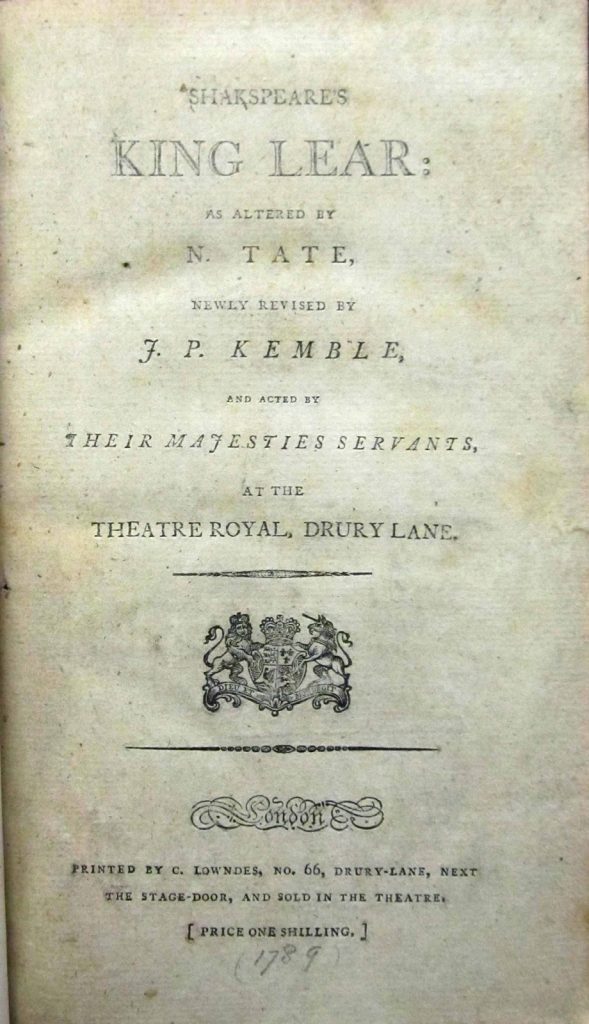

Dr. Rosenbach ’s Shakespeare collection originally included copies of all four folios and the first quarto (single) edition of each play; these were sold to Martin Bodmer in 1952, but the Rosenbach still houses a rich collection of Shakespeareana, not only early folios, but also many fascinating later printings of the plays. This 1676 edition of Hamlet tones down some of the play’s rough language and indicates with quotation marks the extensive cuts that were made in the Duke’s Men’s performance, as “This play [is] too long to be conveniently acted.”

Here’s to both Cervantes and Shakespeare, two towering literary figures whose work has reached readers and audiences for four centuries; may they continue to entertain and inspire generations to come.