When giving tours or talking with people about the Rosenbach, I often get questions about “autographs” and whether the Rosenbach collects them. The word “autograph” comes from the Greek for “self” and “write” and when we talk about an “autograph document” here at the Rosenbach, we are talking about an item that is handwritten by its author (rather than a secretary or copyist). An “autograph document” does not necessarily mean that it is signed.

In common parlance, however, people often refer to autograph collecting in terms of collecting signatures of famous people. In general, that was not Dr. Rosenbach’s approach. He certainly wanted to buy, sell, and collect manuscripts written by famous people, both literary and historical, but he wanted the items to be substantive–he was interested in the whole document, not just the signature. Of course there were some exceptions, for example, there are some Abraham Lincoln documents in which we have only his signature or only Lincoln’s portion of a document with the rest clipped away. Another exception was Dr. Rosenbach’s Signers Set.

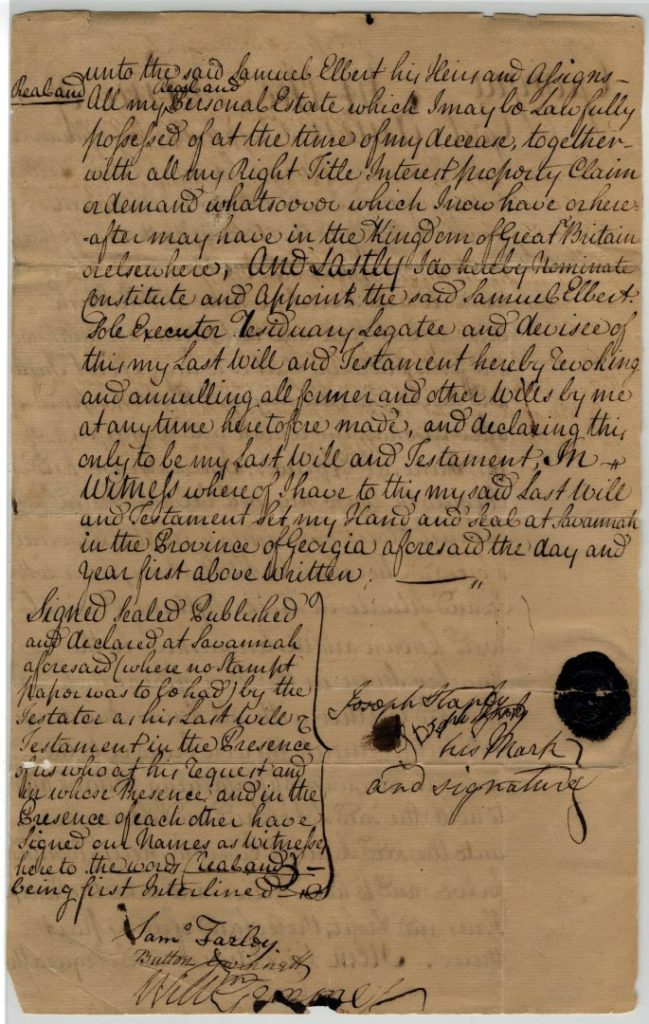

“Signers Sets” are sets of 56 documents, each bearing the John Hancock of a signer of the Declaration of Independence (bad pun fully intended). William Buell Sprague assembled the first such set, beginning in 1815/6 when he was employed by the Washington family, who allowed him to take letters as long as he left copies. Most of the items in Dr. Rosenbach’s Signers Set set are full documents, but the point of the collection was the signatures. For example, Button Gwinnett, a Georgia signer, is represented by a will he witnessed–the only part of the document that is in his hand is the signature.

|

|

Joseph Stanley, will

witnessed and signed by Button Gwinnett.

Savannah, Georgia, 29 May 1770. AMs 545/17, rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia

|

|

|

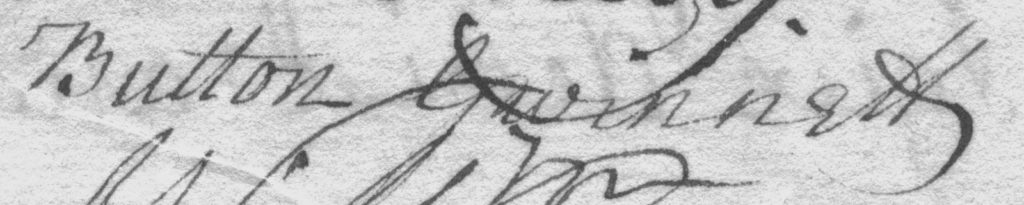

Detail from Joseph Stanley, will

witnessed and signed by Button Gwinnett. Savannah, Georgia, 29 May 1770. AMs 545/17, Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia |

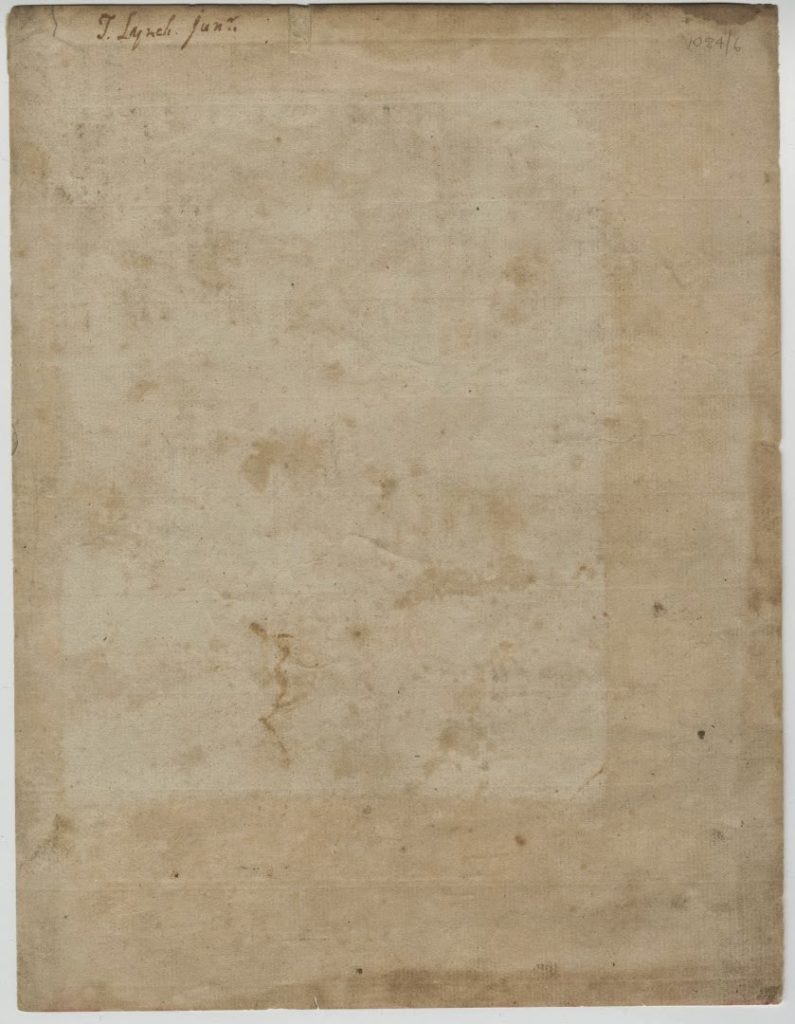

As a corrective to Gwinnett’s media dominance, let’s also remember Thomas Lynch Jr., a signer from South Carolina who died at age 30 and whose signature may actually be the most rare. Dr. Rosenbach noted that “genuine Lynch signatures are excessively rare;” because of that rarity he had to content himself with just a signature, one found on the frontispiece to Sophocles Tragedies.

|

| Thomas Lynch Jr., signature. [ca. 1770] AMs 1084/6. Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia |

With that, I’ll sign off.