Today marks the 250th anniversary of the repeal of the Stamp Act, which was passed on March 22, 1765 and repealed on March 18, 1766. As you may (or may not) recall from your American history classes, the Stamp Act was a tax on printed paper, including newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards. It was strongly opposed by the American colonists, who objected to being subjected to direct taxes passed by a parliament in which they had no representation.

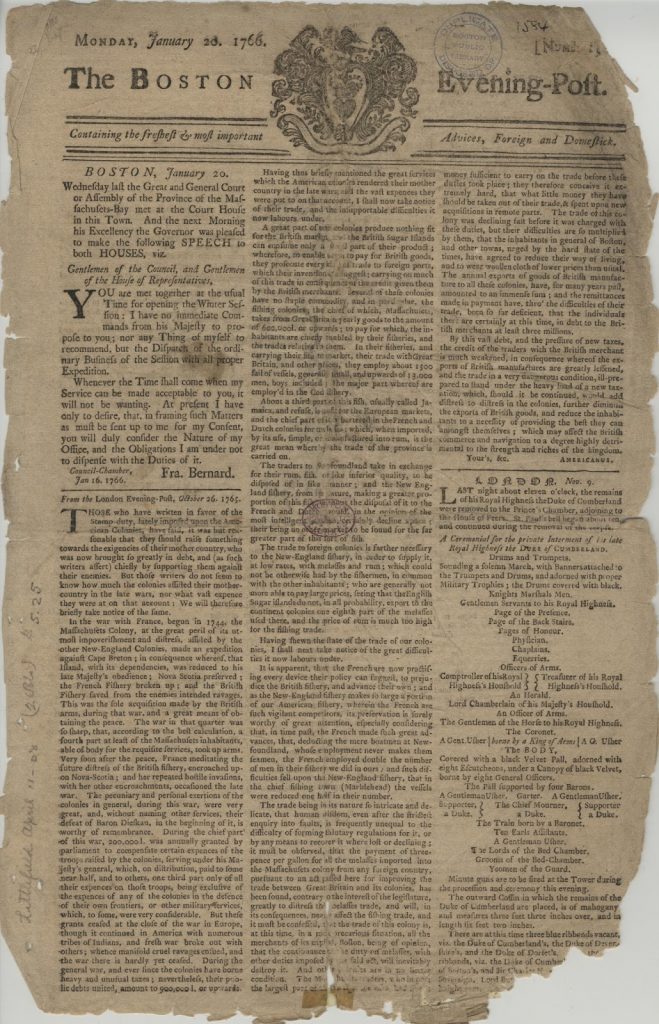

The Stamp Act was levied as a result of the financial distress caused by the 7 Years War, of which the French and Indian War was the American aspect. Much of the tax money was intended for the maintenance of British troops in the colonies. This January edition of the Boston Evening Post prints an article arguing that the colonies were being unfairly maligned for not having paid their share of the war costs.

As the article explains:

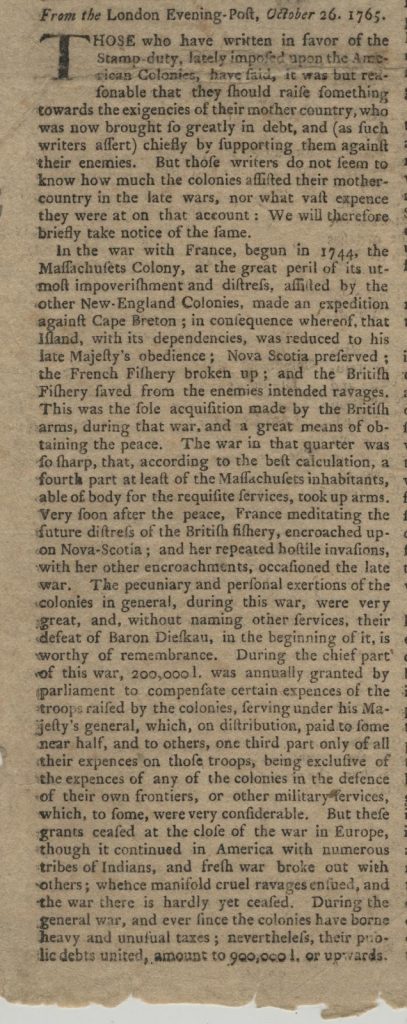

Those who have written in favor of the Stamp duty, lately imposed upon the American colonies, has said, it was but reasonable that they should raise something towards the exigencies of their mother country, who was now brought so greatly in debt, and (as such writers assert) chiefly by supporting them against their enemies. But those writers do not seem to know how much the colonies assisted their mother country in the late wars, not what vast expense there were at on that account. We will therefore briefly take notice of the same.

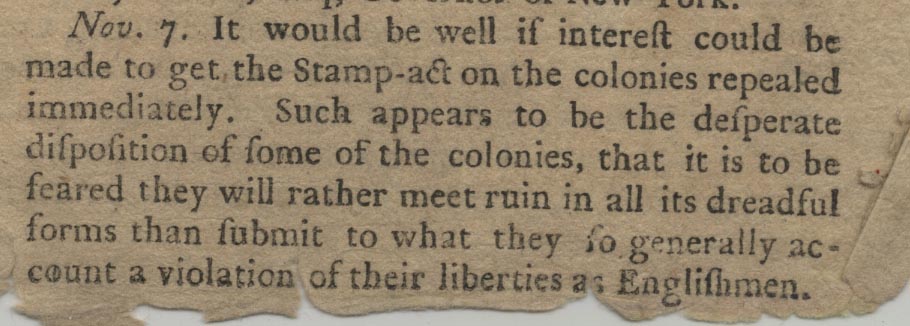

The same paper also includes another article of London news on its second page, which includes the note that:

It would be well if interest could be made to get the Stamp-act on the colonies repealed immediately. Such appears to be the desperate disposition of some of the colonies, that it is to be feared they will rather meet ruin in all its dreadful forms than submit to what they so generally account a violation of their liberties as Englishmen.

The “desperate disposition” referred to in this paper had led the colonists to decry the act in their elected assemblies, such as Virginia’s House of Burgesses, and to convene a special Stamp Act Congress in October 1765 to oppose the measure. It had also led to mob action and threats of violence against the stamp commissioners, who resigned their commissions and fled the colonies.

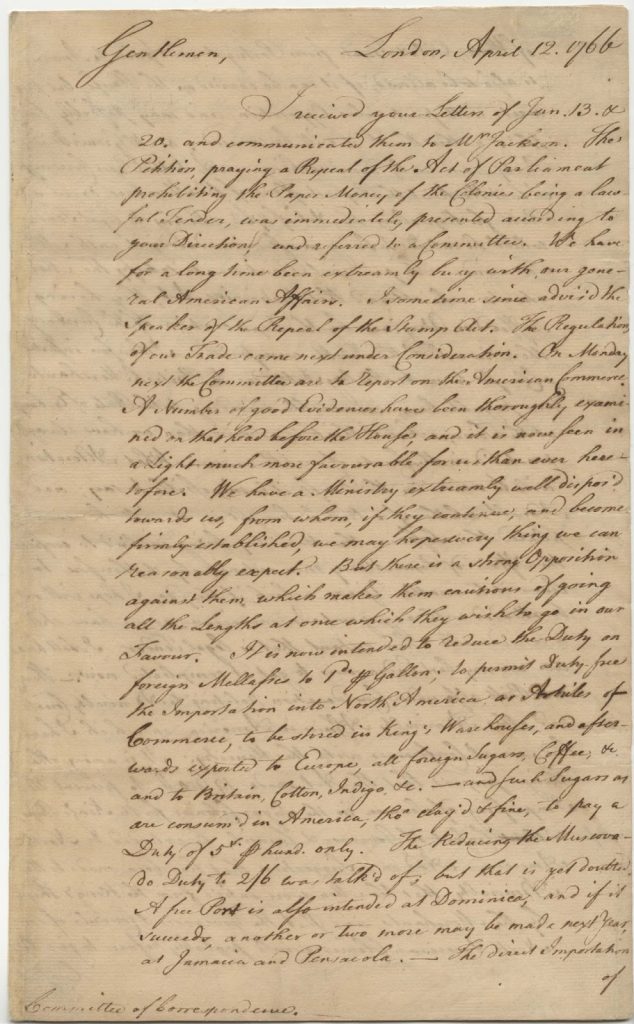

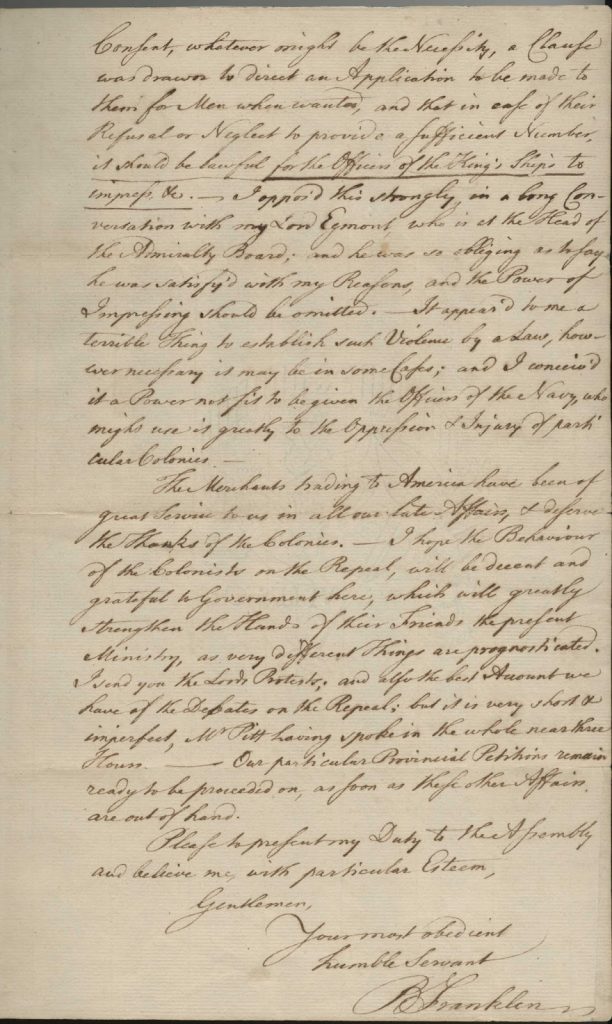

On March 18, 1766, parliament did repeal the bill, although in the Declaratory Act they reaffirmed their right to impose laws on the colonies. In this April 12 letter to the Pennsylvania Committee of Correspondence, Benjamin Franklin mentions the repeal, noting that “We have been extreamly busy with general American affairs. I sometimes since advised the Speaker of the Repeal of the Stamp Act,” before moving on to an update on trade duties and Admiralty courts. The letter also includes updates on a petition “praying a Repeal of the Act of Parliament prohibiting the Paper Money of the Colonies being a lawful Tender.”

He comes back to the Stamp Act in his closing paragraph, writing:

I hope the Behaviour of the Colonists on the Repeal, will be decent and grateful to Government here, which will greatly strengthen the Hands of their Friends the present Ministry, as very different Things are prognosticated. I send you the Lords Protests; and also the best Account we have of the Debates on the Repeal; but it is very short and imperfect Mr Pitt having spoke in the whole near three Hours.

The news of the repeal was, in fact, greeted with joy and public celebration in the colonies, although there were some dust-ups between Americans and British soldiers, as in the case of a Connecticut town where soldiers cut down a liberty pole erected for the repeal.

All in all, the Stamp Act lasted less than a year from passage to repeal and since collection only started in November 1765, it was actually in effect for less than five months. But the act and the responses it engendered from colonists and the British government were indicative of growing tensions that would continue to play out over the next ten years.