Two weeks ago I wrote about Judy Guston’s and my pilgrimage to sites related to Nakahama Manjiro, the mid-19th-century Japanese sailor, translator, and all-around renaissance man whose manuscript we recently loaned to the Sakamoto Ryoma Memorial Museum in Kochi, Japan. This week I thought I’d tell you a little more about the exhibition and the Ryoma Museum. The museum itself is a stunning glass-enclosed building located south of the center of Kochi city, on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

|

| The Sakamoto Ryoma Memorial Museum |

It seems to jut out over the hillside like a ship being launched, and in fact much of the design of the building was meant to echo a sailing ship–a fitting setting for an exhibition about Manjiro. Inside, metal beams soar up to the glass top of the building like the yards of a mast, and there’s even an observation deck on the roof from which you can see up and down the coast of Shikoku.

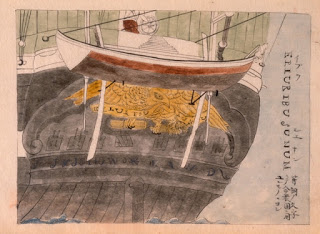

The Ryoma Museum’s exhibition is titled “The World of Manjiro as seen in Hyosen kiryaku,” and deals not only with Manjiro’s tale of “drifting” (as hyo is sometimes translated–the full title of the manuscript is often translated “Drifting: An Edited and Abridged Account”) but also with the other characters involved in disseminating that tale within Japan. There’s Manjiro himself, represented not only by our manuscript, which has drawings and notations in his hand, but by a copy made from our manuscript on display next to it. The copy was also created by the artist and scholar Kawada Shoryo, an official for the local lord in Kochi when Manjiro returned home. This version was fascinating to compare with the Rosenbach manuscript and deserves a blog post of its own. It includes illustrations that aren’t in our volumes (including an albatross, such as Manjiro and his companions found on the rocky island upon which they were shipwrecked) and even the format is distinct, with each page containing printed columns to keep Shoryo’s text tidy. Shoryo himself was highlighted within the exhibition, which displayed some of his remarkable paintings.

The sailors aboard the John Howland, which rescued Manjiro and his four companions from a deserted island after their shipwreck, also had a part to play in the exhibition.

|

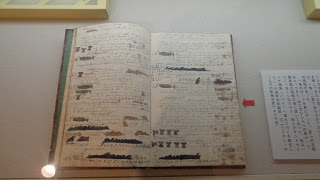

| Sailor’s log book from the John Howland, open to June 1841. Courtesy of the Manjiro-Whitfield Commemorative Center for International Exchange. |

A sailor’s log from the ship is on display, which is an extraordinary record of the daily activities of a whaling vessel. The sailor depicted tails whenever a whale’s flukes were sited, and an entire whale whenever one was pursued and killed. The darker lines of ink appear to be the silhouettes of islands or rocks that the crew could see from a distance. The red arrow on the right points to an entry about picking up five Japanese or Chinese on one island, whom the sailors could not understand, except that by signs they made it clear that they were starving. Mentioned almost in passing, this event signaled a change in fortune for Manjiro, from a poor, illiterate, shipwrecked teenager, to the seafaring, bilingual internationalist he would become over the next ten years.

The museum’s namesake, Sakamoto Ryoma, played an indirect role in Manjiro’s story, though many artifacts from his life were also on display. A minor samurai at the time Manjiro returned to Japan, Ryoma was determined to modernize his country’s government. Influenced by ideas of modern navigation and commerce such as those Manjiro brought back from the United States, and which he partly learned from contact with Kawada Shoryo and Katsu Kaishu (who sailed to the U.S. with Manjiro in 1860 for the first Japanese delegation to Washington), Ryoma forged alliances, helped develop a navy, and eventually negotiated the end of the shogunate and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor. The exhibition also introduces his wife Oryo, who aided Ryoma during their honeymoon in Kyoto when he was attacked by his rivals and wounded. Ryoma’s portrait can be found all over Kochi (his hometown), but our favorite was the cocoa dusting in his likeness on the cappuccino at a cafe next to the museum.

|

| Ryomaccino |

All of these remarkable stories–Manjiro’s, Shoryo’s, Ryoma’s, and that of Captain Whitfield and the crew of the Howland–were meticulously researched and beautifully presented at the museum. The books, manuscripts, and artwork that witnessed Manjiro’s adventures form a remarkable collection of artifacts from around the world and represent collaborations with many public and private collections. Such collaborations would not be possible without the hard work of the staff at the Sakamoto Ryoma Museum and the current torchbearers of Manjiro’s legacy in Japan and around the world, most especially Junji Kitadai. We especially want to thank Natsuki Miura, who curated the exhibition at the Ryoma Museum along with his colleagues Yukie Maeda, Mika Kameo, and Masayo Nakamura. They did a tremendous job bringing Manjiro’s world into focus for visitors to the exhibition.

Verrrry interrresting. Anyone looked into a documentary of Manjiro’s fascinating story.