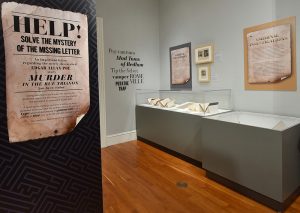

One of the first things you may see when you enter Clever Criminals and Daring Detectives is a wall of extremely odd words in bold typography: Peg tantrums. Tip the velvet. Potatoe trap. What could these strange expressions mean?

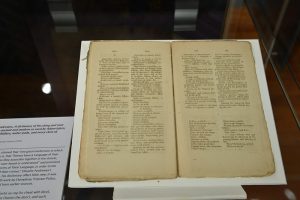

These colorful idioms come from A Dictionary of the Slang and Cant Languages by George Andrews (1809), which is on display in this exhibition. “Cant” may refer to a dialect or even a coded language used by a group, particularly if members of that group want to keep their meaning hidden from outsiders. As you can imagine, people who operate on the shady side of society—thieves, beggars, vagrants—would have good reason to obscure their conversation from casual listeners. On the other hand, everyone else—law enforcement, potential marks, nosy writers—would be desperate to be in on the secret. Cant dictionaries and pamphlets that purported to explain criminal slang were wildly popular as early as the 16th century.

George Andrewes’ cant dictionary was published with the author’s asserted intention to “expose” the language of criminals with the aim of “the more easy detection of their crimes.” It’s less clear how this would work in practice; I can’t help but imagine some ambitious amateur gumshoe creeping around the less fashionable addresses in London with cant dictionary in hand, stealthily flipping through the pages to keep up with an overheard criminal plan. But this would have proved an ineffective means of detecting criminals, as Andrewes’ definitions were taken almost word-for-word from an earlier work by Humphrey Tristram Potter, which itself was drawn from even older sources. Few cant dictionary writers could lay claim to first-hand knowledge of the jargon, although most implied that they did.

So if cant dictionaries weren’t a useful or effective tool in a crime-buster’s toolkit, why were they in such high demand that writers kept churning them out for centuries? Perhaps the cant dictionaries share some of the characteristics that made detective fiction so popular in the nineteenth century. There is certainly the allure of a furtive glimpse into the underworld: the average law-abiding citizen may have no reason to conceal their meaning behind mysterious words, but it’s rather titillating to think about those do. Fiction writers certainly made good use of cant dictionaries in writing dialogue for shady characters: notably, Charles Dickens was highly praised for his depiction of Oliver Twist‘s band of pickpockets, whose patter relies heavily on Andrewes’ precursors in cant research.

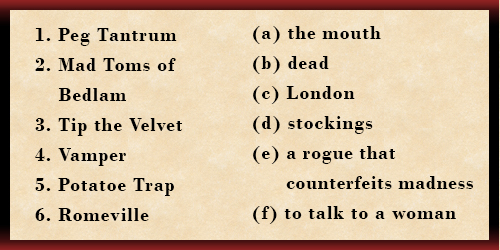

Perhaps there is also the pleasure in deciphering a code or unravelling a riddle: if a potatoe trap isn’t a device to catch tubers, then what is it? It’s a little linguistic puzzle to solve. See if you can match the meaning to the cant below. The answers are at the bottom of this post; click and drag to highlight and make them appear.

Answers: [1.(b) 2. (e) 3. (f) 4. (d) 5. (a) 6. (c)]