Kathy is away this week working on something Sherlockian

(which I’m sure you’ll read about here soon).

In the meantime, this week’s blog post is motivated by perhaps the most

notorious episode of NPR’s This American Life, which was the topic of lunchtime

conversation recently at the Rosenbach. The

theme: fiascos. If you want to hear

about the worst production of Peter Pan ever staged or how a

minor change in a local radio program turned into a state-wide cultural throwdown

then give a listen to the episode. If

you want to know which fiascos are hidden behind the covers and enclosures of

objects in this museum…well, that’s what I’m here for. Consider me Mr. Fiasco. I’ve got three stories of fiascos related to

objects in our collection, which I’ll post separately to avoid any single post becoming

an outrageously long…well, you know.

|

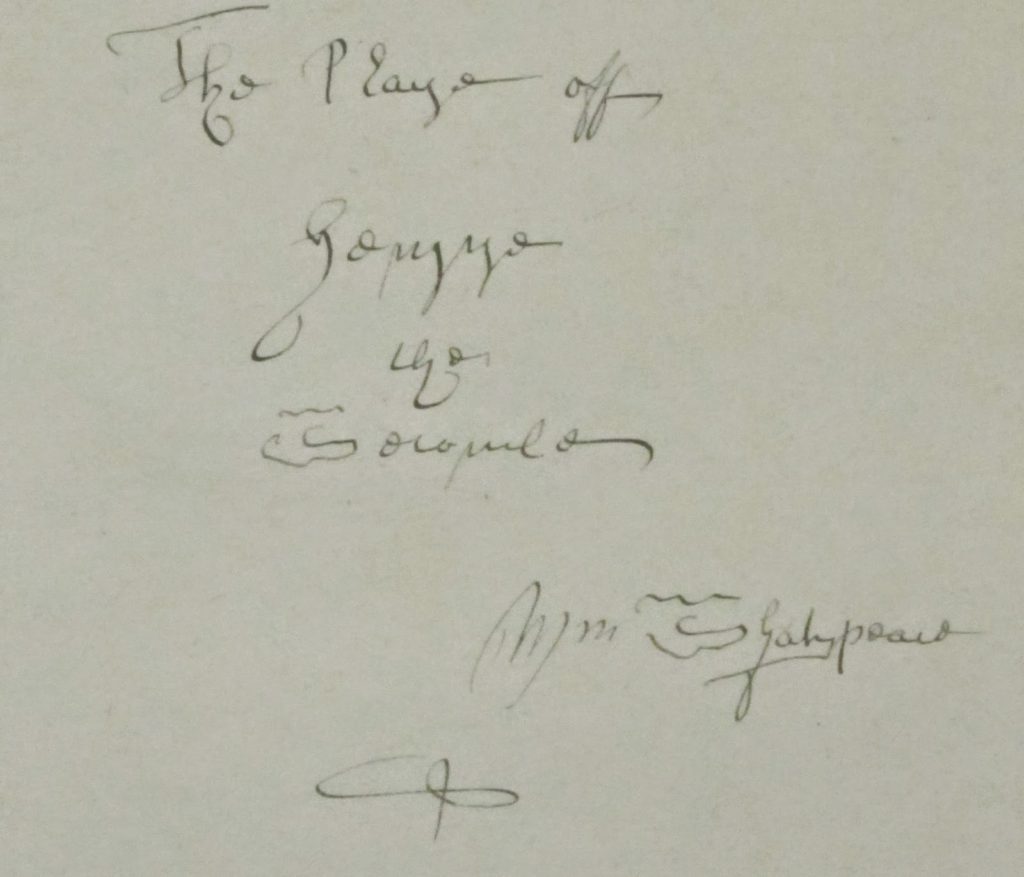

| Henry II, a “newly discovered” Shakespeare play forged by William Henry Ireland. The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia, EL3 f.I65i MS4. |

Shakespeare is always good fodder for a fiasco. So many of his plays draw their life force

from them—even plays he didn’t write!

That’s where William Henry Ireland comes in. This late 18th-century law clerk’s

specialty was forging documents supposedly in Shakespeare’s hand (no authentic

hand-written documents by Shakespeare are believed to have survived apart from

a few signatures, and forgers do abhor a literary vacuum). He supplied the world with letters and

declarations by Shakespeare, fragments of King Lear and Hamlet in

manuscript, even a lock of Will’s hair (so that’s where all the hair went!)—all supposedly

discovered within a vast trunk of documents belonging to a friend, Mr. H., who

wished to remain anonymous. The thing

about a fiasco is the snowball effect of rolling disaster that it creates, and

around 1795 Ireland’s fiasco began to roll downhill. Droves of people came to the Ireland family

home to lovingly inspect the documents, many of them exhibiting an almost

religious fanaticism. Samuel Ireland,

William Henry’s stern father and Shakespeare enthusiast, was so enraptured by his son’s discoveries that he

couldn’t help himself—he had to know more about Mr. H. So William Henry then had to impersonate Mr.

H. in a lively correspondence that he kept with his father, all the while

forging his magnum-opus, a lost tragedy called Vortigern and Rowena. When news of that play’s “discovery” reached

the ears of theater impresario Richard Sheridan he knew he had to put on the

first “new” Shakespeare play in more than a century. Meanwhile, the first voices of dissent made

themselves heard.

|

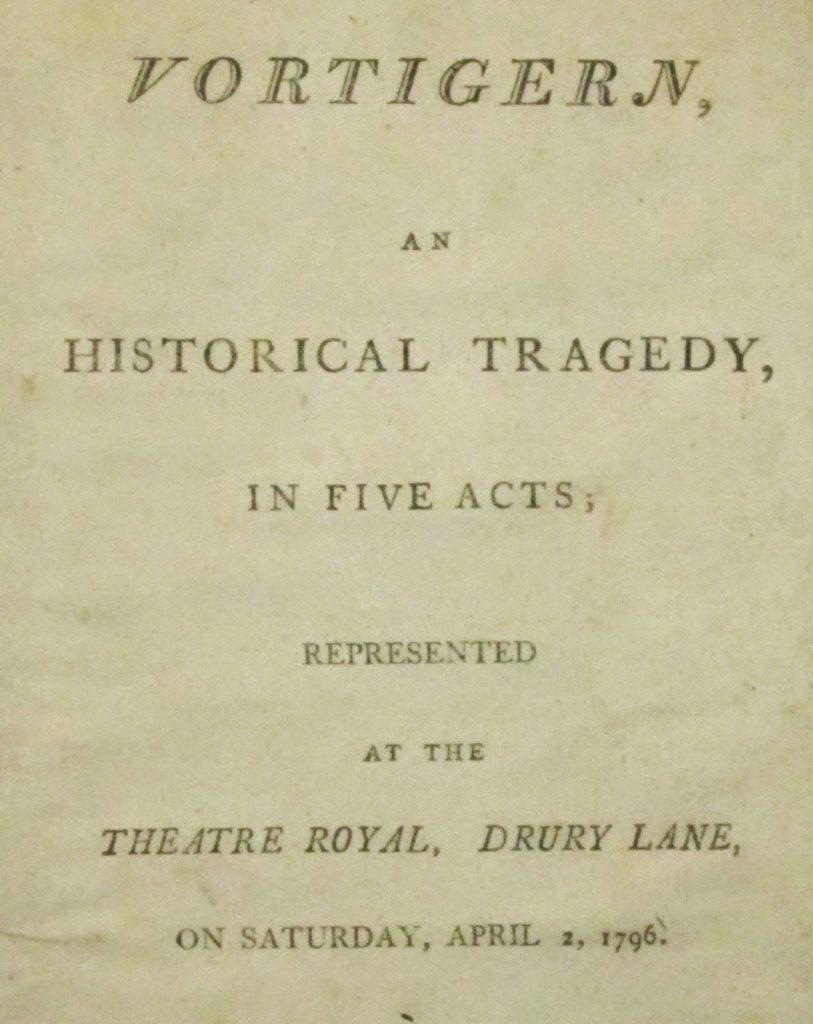

| Transcription of Ireland’s forged Vortigern. The Rosenbach of the Free Library, EL3 f.I65i MS3. |

Sheridan bought the rights to perform Vortigern at

Drury Lane theater, with the famous J. P. Kemble in the starring role (despite the actor’s skepticism of the play). Just before

the first performance of Vortigern on April 2, 1796, Shakespeare scholar

Edmond Malone dropped the gauntlet, publishing a widely-read criticism of

Ireland’s supposed Shakespeareana as a vile hoax.

|

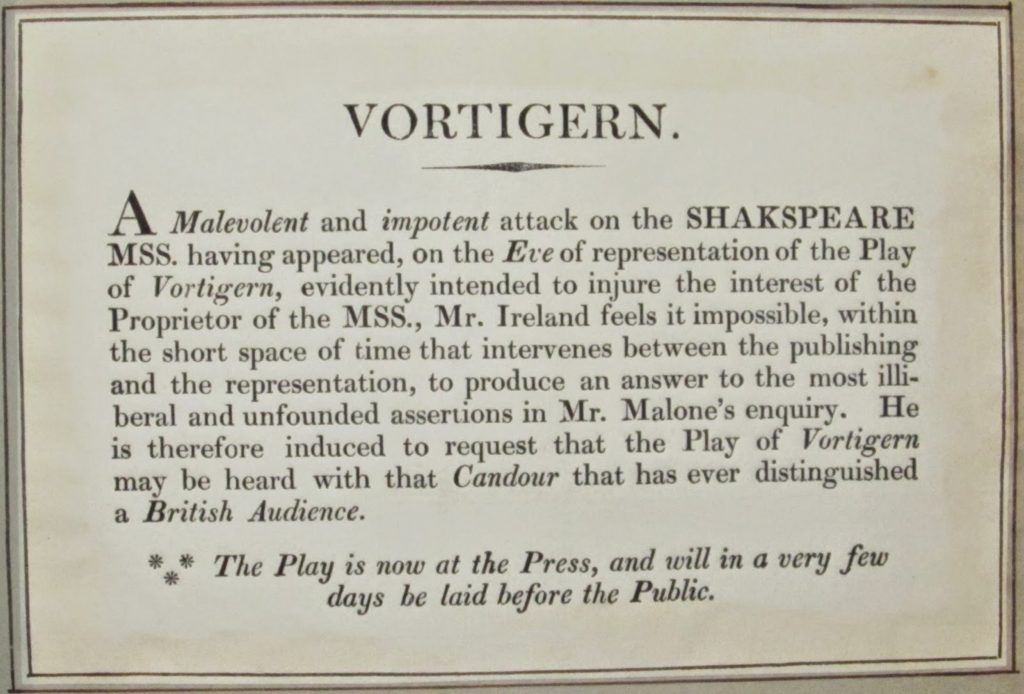

| A hand-bill distributed during the performance refuting Malone’s claims. The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia, EL3 f.I65i MS3. |

The night of the performance Drury Lane was a powder keg. Supporters of the Irelands and their discoveries, as well as doubters

who agreed with Malone’s assessment packed the theater. The

audience gave the play a chance to prove itself, listening without much quarrel

to the first few acts. It was Kemble

himself who gave vent to the simmering tensions of the dissenters in the crowd

when he pronounced these lines—mockingly addressed to Death—towards the end of the

play: “Thou clapp’st thy rattling fingers to

thy sides; And when this solemn mockery is ended—”

| The “solemn mockerye” passage from William Henry Ireland’s forged Votigern play. The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia, EL3 f.I65i MS3. |

You had to be there: the way that Kemble spat

the last line at the audience apparently left no question at which mockery he

was addressing. The crowd picked up on

it and started jeering and whistling.

Kemble let this go on then fired his second torpedo, repeating the line with an equal measure of

disdain for the same reaction. When the

play finally ended, it was announced that Vortigern would be shown again

the following Monday, which was greeted with loud booing from the crowd. Tempers were so high by then that a fight broke out in the pit between the

booers and the play’s supporters. Chaos

ensued. The sanctity of the Bard was at

stake and the theater became the battleground for this holy war. Kemble hastily took the stage to say, on

second thought, they’ll do a different play on Monday.

eventually broke up and everybody went home, but the Vortigern fiasco continued in print.

Newspaper reviews and much word-of-mouth excoriated the production and largely blamed the pretentious Samuel Ireland for the forgeries. Samuel refused to renounce them, and instead published a critique of Malone. This put immense pressure on William Henry Ireland to confess and clear his father’s name. He eventually did, though his father never

believed that his son had the talent or intelligence to play at being Shakespeare for as long

as he had, and the critics assumed it was some sort of trick Samuel had forced his son into doing. Not surprisingly, after his

exposure William Henry’s reputation was in the gutter. But since he was known as a forger, why not

make the most of it? He began to copy

his own forgeries and sell them as the original forgeries. You can see them here, including his copy of Vortigern—is

a forgery of a forgery a fiasco?

Mr. Fiasco is Curator of the Maurice Sendak Collection at The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Mr. Fiasco is Curator of the Maurice Sendak Collection at The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia.