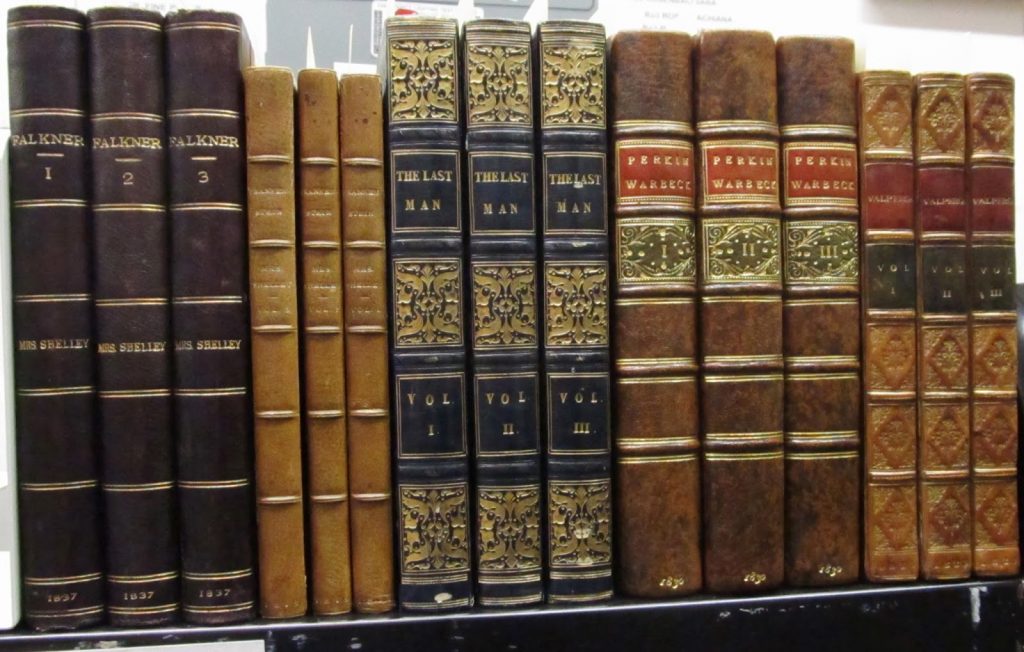

We’re delighted to announce that the Rosenbach has recently acquired a rare first edition (1818) of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, as well as first editions of Shelley’s novels Valperga (1823), The Last Man (1826), The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830), and Falkner (1837). These terrific additions to our collections of English Romantic literature were purchased thanks to major support from the B.H. Breslauer Foundation and gifts from Mark Samuels Lasner and Clarence Wolf. Here they stand in a row awaiting processing before they appear on our library’s shelves.

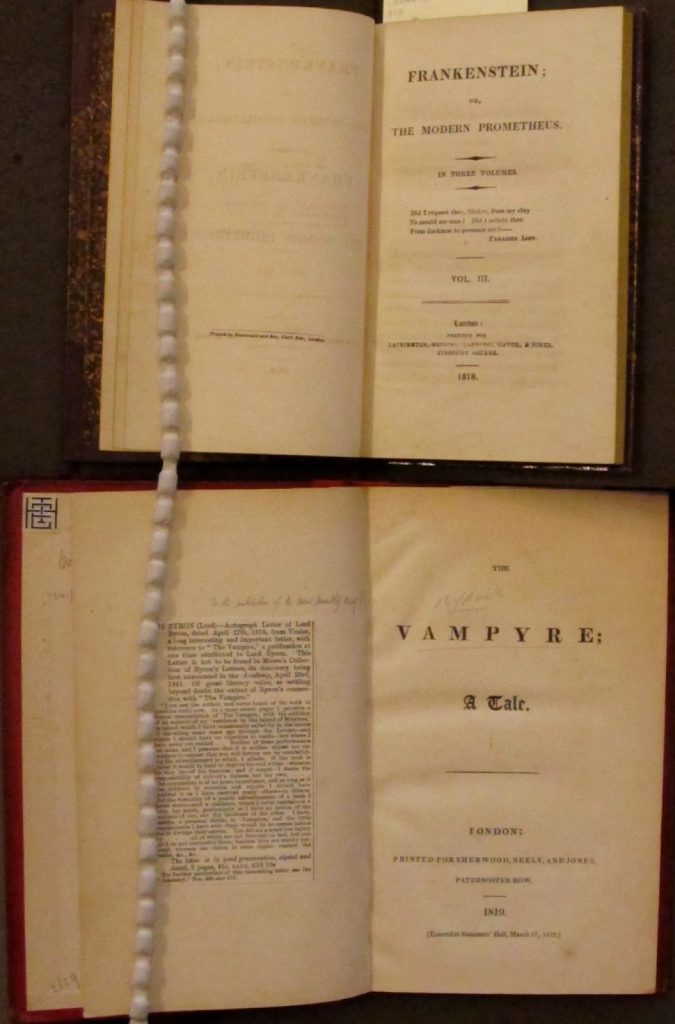

For as big an impact as Frankenstein would have in launching science fiction as a genre and taking Gothic fiction in a new direction, you’ll notice that the 3-volume novel (second from the left in an ochre binding) is the smallest of the lot despite being the best known work by Mary Shelley. In fact, she was not acknowledged as author of this first edition and only 500 copies were printed. Its success encouraged her father, writer William Godwin, to publish a new 2-volume edition in 1823 that contained hundreds of unauthorized word changes, after which Shelley published a 1-volume newly revised and expanded version in 1831. Her manuscripts for the novel are housed at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library and are wonderfully digitized and available online at the Shelley-Godwin Archive. The story of why she wrote Frankenstein is the well-known and dramatic tale of a group of writers scaring each other with ghost stories during the frozen summer of 1816 (if you have no idea what I’m talking about, see Kathy’s previous blog posts on this topic!). The other novel about an infamous monster to come out of that same gathering was John William Polidori’s The Vampyre, published a year after Frankenstein. Call me sentimental, but it seemed fitting to reunite first editions of each given their shared history!

If literary monsters are your thing you might look forward to an exciting exhibition we’re assembling for fall 2017. A major grant from the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage will allow us to begin work on Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Monster Within, an exhibition about the scientific and ethical concepts at the heart of both Shelley’s and Stoker’s celebrated novels. We’ll share plenty more details about this exhibition and its related programs in the near future.

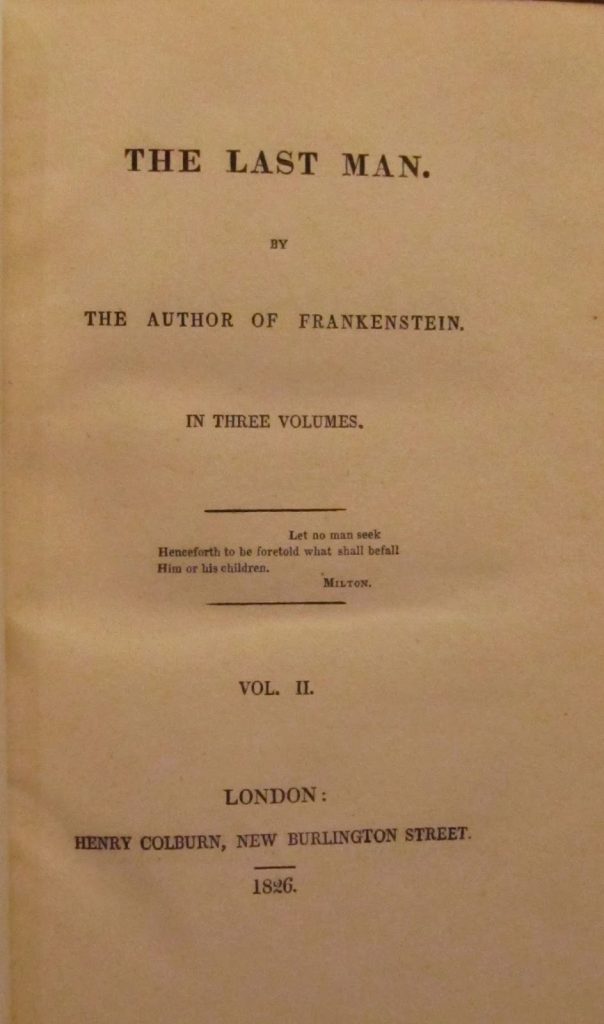

Shelley’s other works–Valperga, Perkin Warbeck, and Falkner–are deserving of blog posts in their own right (not to mention Lodore, 1835, which wasn’t part of this acquisition). Last but not least…but still last, is The Last Man, an 1826 novel by Mary Shelley. Its characters are loosely based on the same personalities who played a role in Mary’s creation of Frankenstein, such as her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron, but their ideals and intellects are put to a challenge that neither poet had to endure in life: the apocalypse! Mary Shelley envisioned a world at the end of the 21st century that bore a striking resemblance to that of the 1820s, albeit with some wild innovations: yes, the Greeks were still fighting for their independence from the Ottomans but hot air balloons with “feathered wings” are also a common conveyance in the British Isles. By the year 2092 a plague that is vaguely understood to have originated in the east gets spread by victorious Greeks to other parts of Europe. England is, of course, the last country to fall victim to the pestilence in which “the air is empoisoned and each human being inhales death.” The plague makes its way around the globe and gradually kills off every human being until only the titular last man remains. Exacerbating the ravages of the plague are a series of natural disasters, including the rising of a black sun, earthquakes, and floods that submerge half of England, as well as social disruptions familiar to fans of modern apocalyptic fiction (at one point American marauders cross the Atlantic, plunder Ireland, and invade England). Shelley was certainly way ahead of her time, and you can bet we’ll be exploring these newly acquired editions in exhibitions and programs over the coming years.