This blog post was written by Andrew White

With letters, photographs, first editions, and manuscripts of Oscar Wilde in our collections, many facets of Wilde and his life can be glimpsed at The Rosenbach. So much so, I sometimes struggle with what exactly to foreground: his spectacular gift for words, his careening success, or his tragic fall. Though we can’t visit The Rosenbach in person just now to go Behind the Bookcase with Rosenbach collections, we can see Oscar Wilde at two distinct points of his life’s trajectory here on the Rosenblog. Two handwritten notes from Wilde to friends are in our collection, and reproduced below. One is written by Wilde as a young man about to make his great leap into celebrity. The other is written at what should have been his middle years, after he’s plummeted back to earth.

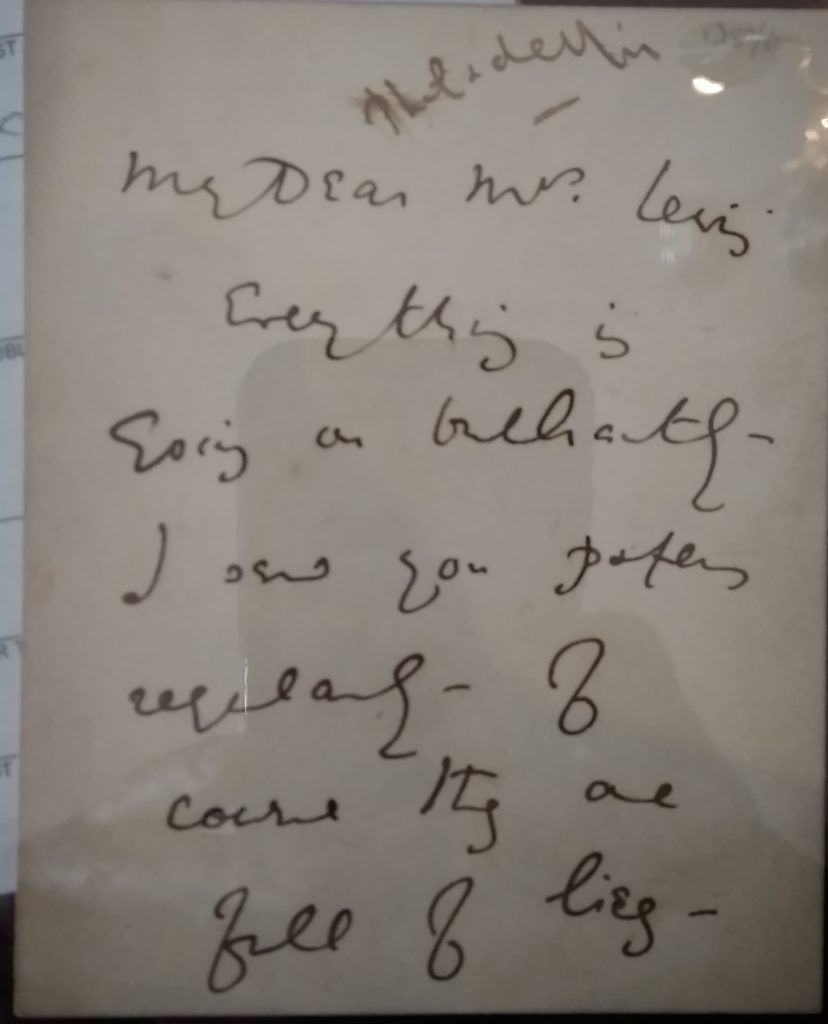

The first note, written when Wilde was 27, is shared on our Irish Authors Behind the Bookcase: an ebullient note Wilde wrote to Mrs. George Lewis in January of 1882. “Everything is going on brilliantly,” Wilde writes, as he was beginning his debut lecture tour on our side of the Atlantic, even if “the papers… are full of lies…”

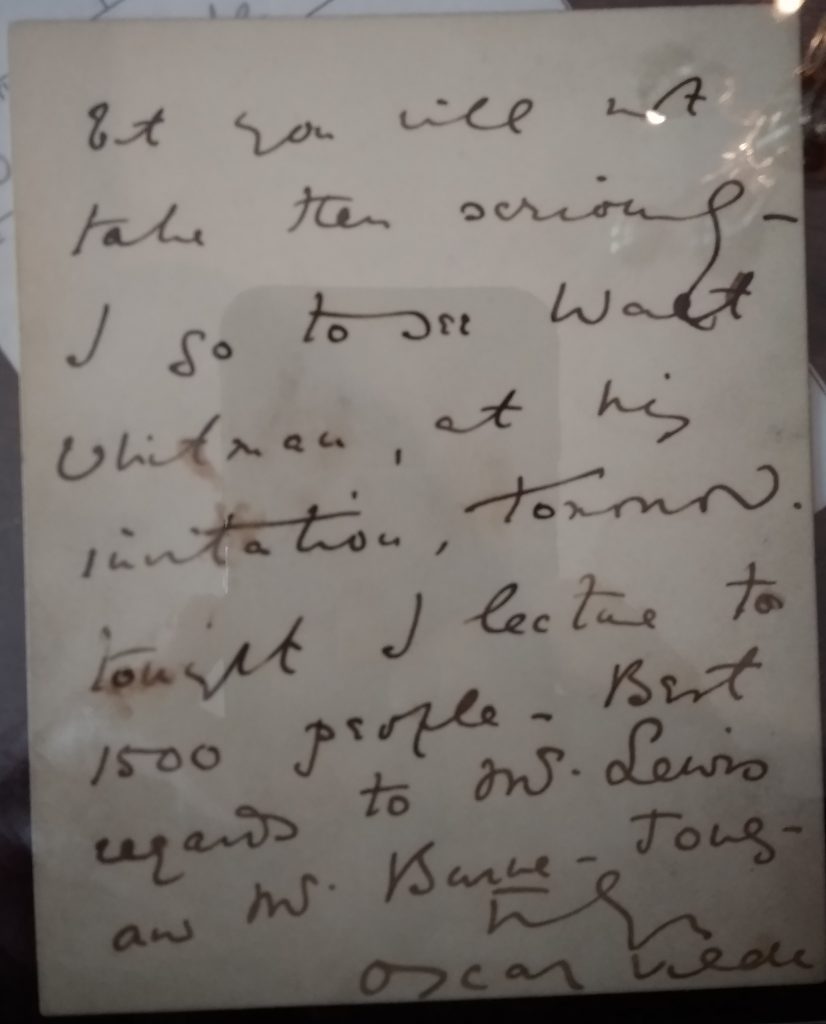

On the flip side, Wilde brags to Mrs. Lewis that he is going to Camden to “see Walt Whitman, at his invitation, tomorrow.” Wilde doesn’t mention that he publicly courted the invitation through flattering Whitman in a Philadelphia Press interview, nor does he mention that the New York Times described his first lecture as “an opportunity to laugh that was readily seized” (though whether the audience was laughing with or at Wilde isn’t clear from the article).

Young Wilde was determined to make the most of any opportunity to promote himself and wasn’t daunted by having been sent on the tour solely to provide an example of what Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience was satirizing: the exquisite, melting madness of the counter-Victorian Aesthetic Movement. Richard D’Oyly Carte was the impresario of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, and sent Wilde to the states for the sole purpose of helping American audiences understand what the target of lyricist Arthur Sullivan’s satire was. D’Oyly Carte may have been promoting Wilde solely as an object of ridicule, but Wilde was no one’s patsy.

Or wasn’t, that is, till he met Lord Alfred Douglas, a self-consciously pretty aristocrat who was equal parts Dorian Grey and Oswald Mosley. Wilde often calls Douglas “Bosie,” which is a decomposed version of the nickname his lordship’s mother gave him, “Boysie.” That this noxious lordling and his cloying nickname are now forever embedded in literary history is the only real crime Wilde is guilty of. Lord Alfred goaded Wilde into participating in his family’s favorite bloodsport, litigation, and suing Bosie’s furiously pugnacious father the Marquess of Queensbury. That it’s a bad idea to take someone to court for accusing you of being what you actually are (in this case, a “posing sodomite”) is clear to anyone who isn’t fatally love-blind. In trying to please Bosie, Wilde stumbled into the legal limelight, or specifically, section 11 of the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which outlawed even more consensual same sex behaviors than its precursor had in the time of Henry VIII (which can be summarized as: whatever you fellows get up to is fine, shy of penetration).

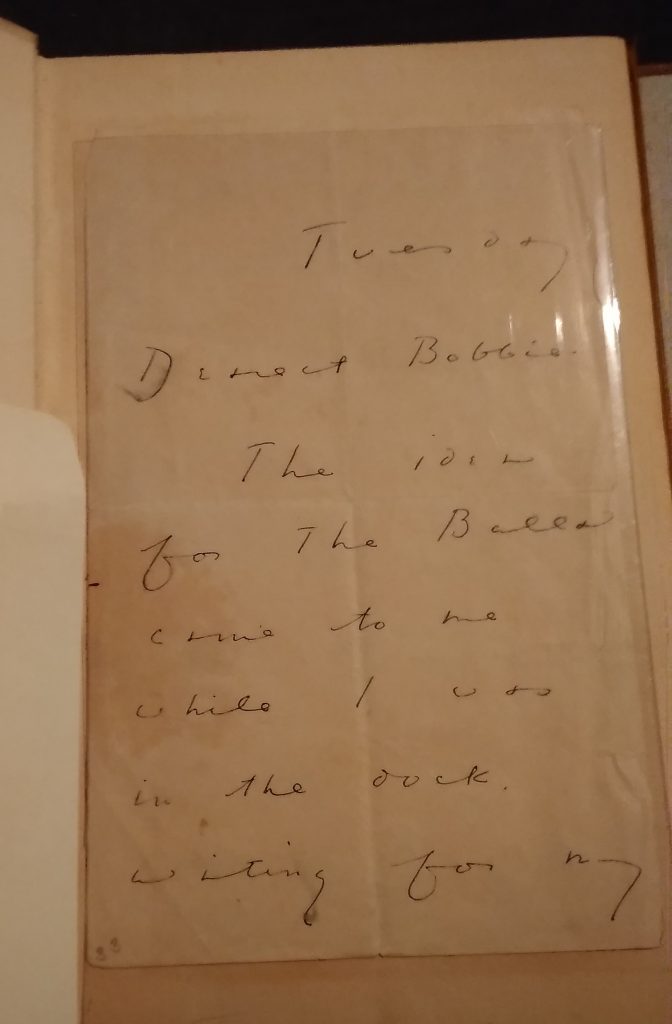

We have, in Wilde’s own hand, a note he wrote to his loyal friend Robert Ross after serving two years of hard labor for Bosie’s whim:

“Dearest Bobbie, the idea for the Ballad came to me while I was in the dock, waiting for my sentence to be pronounced.” Wilde’s handwriting here has lost some of its former bounce, as an older Wilde defends himself from Douglas’s claim that he had given Wilde the idea for the Ballad of Reading Gaol. Published in 1897, Reading Gaol drew on Wilde’s prison experiences and gives a sense of the brutality of prison labor known intimately by any convict of the time:

We tore the tarry rope to shreds

With blunt and bleeding nails;

We rubbed the doors, and scrubbed the floors,

And cleaned the shining rails:

And, rank by rank, we soaped the plank,

And clattered with the pails.

We sewed the sacks, we broke the stones,

We turned the dusty drill:

We banged the tins, and bawled the hymns,

And sweated on the mill:

But in the heart of every man

Terror was lying still.

Wilde’s prison address was cell block C, landing 3, cell 3; C.3.3. became the identity that Wilde published Reading Gaol under. That the poem brought a small income to ease the penury of his last days is a testament to the same resourceful spirit that turned a parody lecture tour into a P.R. triumph. “Bosie mustn’t say he originated it,” Wilde sighs, of the poem born of his life’s nadir.

He ends the letter to Ross with a line that scalds the hearts of all who read it: “I am very miserable. Ever, Oscar.”

From an unstoppable 27 year old crowing about how brilliantly everything is going to a heartbroken and health-broken man in his forties confessing misery, The Rosenbach collections bring you Wilde at his heights and his depths. The first of these notes is featured in our Irish Authors Behind the Bookcase presentation, the second in 19th Century Lesbian and Gay Lives. As I’m preparing to present either Behind the Bookcase, I find myself struggling to find the meaning in these tesserae of a beautiful, shattered mosaic of a life.

As always, Wilde has the answers. “The important thing,” he writes in his late testament DeProfundis “the thing that I have to do… is to absorb into my nature all that has been done to me, to make it part of me, to accept it without complaint, fear, or reluctance. …To deny one’s own experiences is no less than a denial of the soul.” I may worry that balancing Wilde’s dramatic triumphs with his equally dramatic downfall may be too much to ask of an object or two in ten minutes of an hour-long presentation, but if I listen to Wilde it becomes clear: All fragments of his story are equally true; all fragments of his story are equally representative.

It is rather sad to see that your account of the trial of Wilde vs. Queensberry is so one-sided. Solely to blame Lord Alfred Douglas for what happened is inaccurate. To suggest that had it not been for him, the trial would never have taken place, is peculiar, to put it mildly. In “De Profundis” one does NOT read that Oscar Wilde had tried to have Queensberry arrested after the latter had vainly endeavoured to disturb the premiere of “The Importance of Being Earnest.” The attempt failed, because the staff of the theatre refused to appear as witnesses for the prosecution; and without their testimonial, any attempt to have the Marquis prosecuted was doomed to failure. Douglas was wholly unaware of his friend’s effort to have Queensberry arrested, as he (Douglas) was abroad at the time. “I had not wished you to know,” Wilde wrote to him. One would have hoped that research by the likes of Rupert Croft-Cooke had done something to adjust the balance. People will always say (and here they echo “De Profundis” once more) that Bosie was the ruin of Wilde’s art; that Wilde could never write a single line as long as he was in Bosie’s company. Well, go to the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library and have a look there at the first draft of “An Ideal Husband,” written in Wilde’s own hand; and you will read there Wilde’s remark: “Written in the company of Alfred Douglas.” There is much more one could say, but I shall stop here; only to add this thought which occurred to me some time ago: what was the best thing Oscar Wilde ever did in his life? Maybe his decision to take Lord Queensberry to court. Had he won his case, he would have left the Old Bailey, a rehabilitated straight family father, grossly maligned by a mad nobleman who would have been punished for insinuating that the playwright preferred his own sex. Instead, he was sent to gaol–his cruel fate inspiring Dr Magnus Hirschfeld to begin the first campaign to save gays worldwide from prejudice and prosecution.

As you succinctly note ; Wilde was no one’s patsy & yet you portray him as being just that in how you describe Lord Alfred Douglas. Let’s get this straight (whoops!) They loved each other & yes it was disastrous for Wilde but they continued to see one another after he left prison. Is it that which you find so reprehensible? I might suggest you are a little envious of ‘Bosie’ even though he is now dust. Nothing is ever that black & white, good & bad.

Thanks for opening this interesting topic. I love Oscar Wilde’s plays but honestly knew little about his life save for a few details about his sexual orientation. Without the context you provide to these notes, I would have missed their significance. I think the elevated tone of the other comments here is a kind of testament to how complex he was as a literary figure. There is much one could debate and consider about Wilde. You post brought him to life for me and made him multi-dimensional. I look forward to the future when I can visit the museum again in person.