Dear Friends,

I hope you are all well this week. As many of us work at home during this time of quarantine, we adjust for better or worse to alternative behaviors and settings than those we have at our workplaces. I will share that I am writing to you from an otherwise lovely space, the breakfast table in my bedroom. It is not a particularly ergonomically appropriate workspace. It was hardly a surprise when—at seven weeks into our current situation and with many hours of typing behind me—I developed a stress-induced wrist condition.

This disclosure is not intended to induce sympathy, as there are so many people enduring much more serious ailments at this time, but merely to introduce three lines of discussion: (1) my brief but related post (alas, typing with a brace is a wee bit slow); (2) my reunification with our city en route to the doctor’s office, and my thoughts of the novel you are now consuming; and (3) my deep appreciation for everyone who provides us with care, both at this time and all the time.

So, no, my doctor said I could still type, so she did not eat my homework this week. But the brace that encloses my (left) hand and wrist (but leaves my fingers free) did make me think of James Joyce and his famous (left) eye patch:

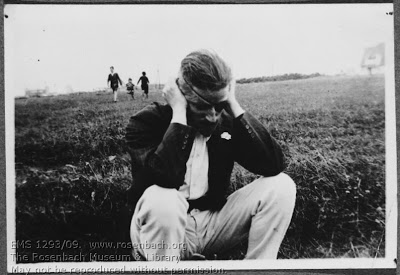

Joyce met English painter Frank Budgen in Zurich in 1918. They became drinking buddies, as evidenced in part by Joyce’s poem dedicated to him, “To Budgen, Raughty Tinker,” in which he lovingly called him “a boozer, bard, and canvas dauber.” Budgen would write about Joyce, as well, in his memoir of their friendship and Joyce’s famed novel, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses (1934).

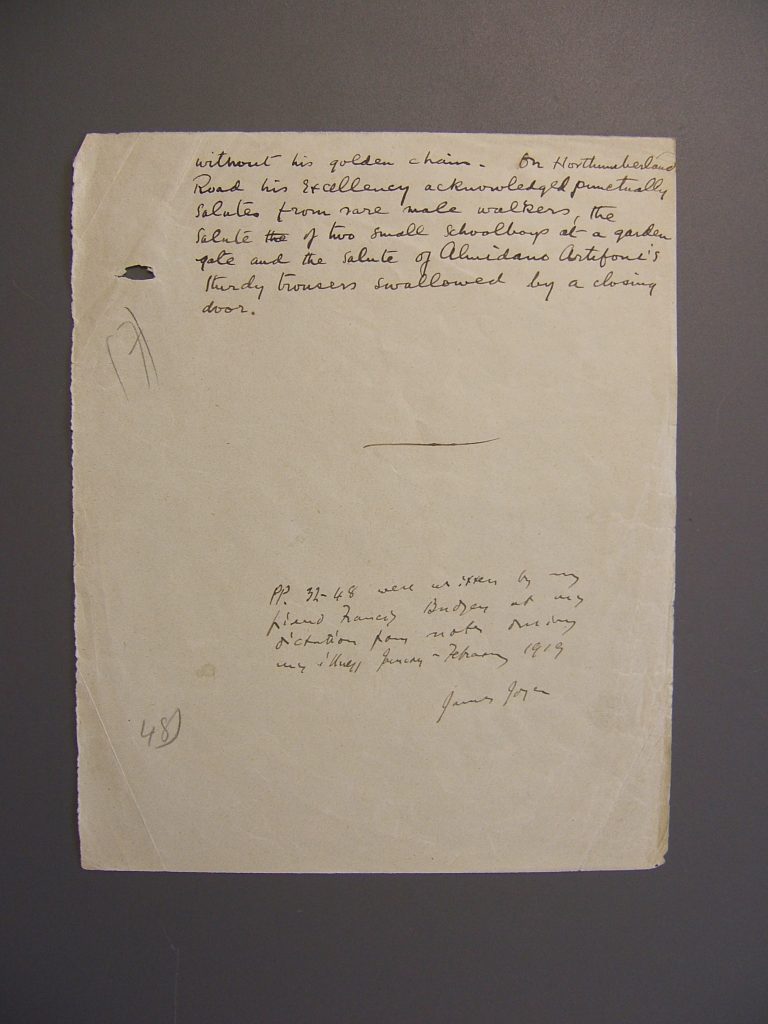

But more to the point of our story today, Budgen played a significant role in the making of The Rosenbach manuscript. Joyce struggled with another bout of iritis during the writing of the Wandering Rocks episode—which you have just read this week (if you are keeping up with Ulysses Every Day). Towards the completion of the episode in early 1919, Joyce dictated a portion as Budgen wrote. Knowing that John Quinn (see my first week’s post for more on Quinn and the purchase and sale of the manuscript) was concerned with the appearance of the manuscript he was purchasing, Joyce wrote a note at the end of this section indicating “pp. 32-48 were written by my friend Francis Budgen at my dictation from notes during my illness January – February 1919/ James Joyce” (see this note pictured below):

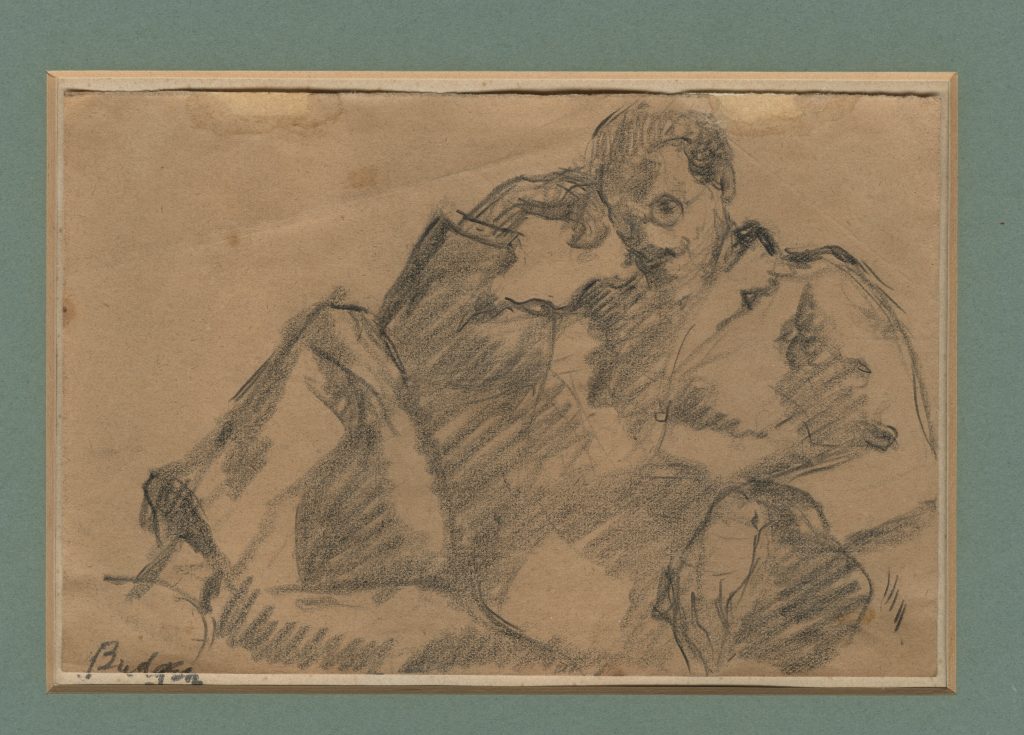

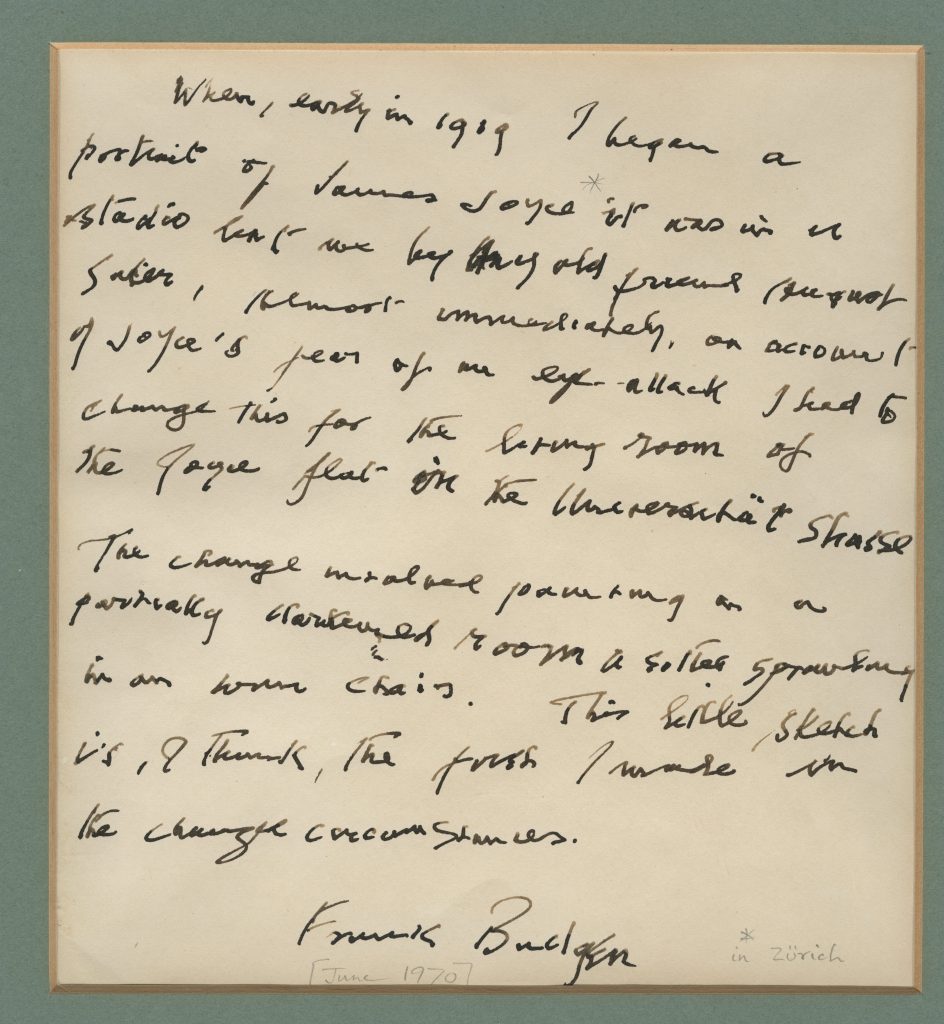

Perhaps just before this dictation took place, Budgen—in his studio—began to sketch his friend Joyce. But, as he explained in a handwritten note, Joyce began to “fear an eye attack” and they had to move to “the living room of the Joyce flat,” where Budgen continued to draw. The outcome was the sketch shown below. Because of the date and circumstances, the sketch and note are forever linked to the section of Wandering Rocks in The Rosenbach manuscript that Budgen and Joyce wrote in tandem.

So, as I share this small bit of literary history with you today, I think about how difficult it must have been for Joyce to write impeded by his eye ailment, but how much of his walk through Dublin could be reconstructed not just from his notes, as in this instance, but from his head and heart. I hadn’t been out of my house—except for a few surrounding blocks—for the weeks since we’d been asked to stay at home until I needed to seek medical assistance earlier this week. I’d missed walking across the city and had an idea of what I thought Philadelphia “was.” The landscape seemed changed. We have some re-creating to do. Can we reimagine our cities, making them creative, inclusive, and equitable places for the future? I am hopeful. Are you?

I’ll end with a note of gratitude to everyone who’s out there every day doing the hard “essential” work, whatever your job or your paygrade. Thank you.

Next week: on to Cyclops!

Be well.