In March of 1926, the Rosenbach brothers had made it. Abe was traveling back and forth to England for high profile and wealthy clients, brokering deals for some of the rarest and most historically important books in the Western Hemisphere. Phil ran the retail side of the business, managing two stores filled with highly provenanced decorative objects.

The Rosenbach family, sisters Rebecca and Miriam, and brothers Abe and Phil, were newly moved into 2006 Delancey Street in Philadelphia, a substantial brownstone on an exclusive and peaceful treelined street. Taking care of the home front was 60-year-old sister Rebecca. Rebecca had never married and she ensured a pious, Kosher, and family-centered homelife for them all. She was also the primary caretaker for her younger sister Miriam, who is known to have had a cognitive condition, possibly a form of Down’s Syndrome.

Here are Miriam (left) and Rebecca (right):

In early March 1926, Abe headed off to England. Almost as soon as he left, Rebecca and Miriam got the flu.

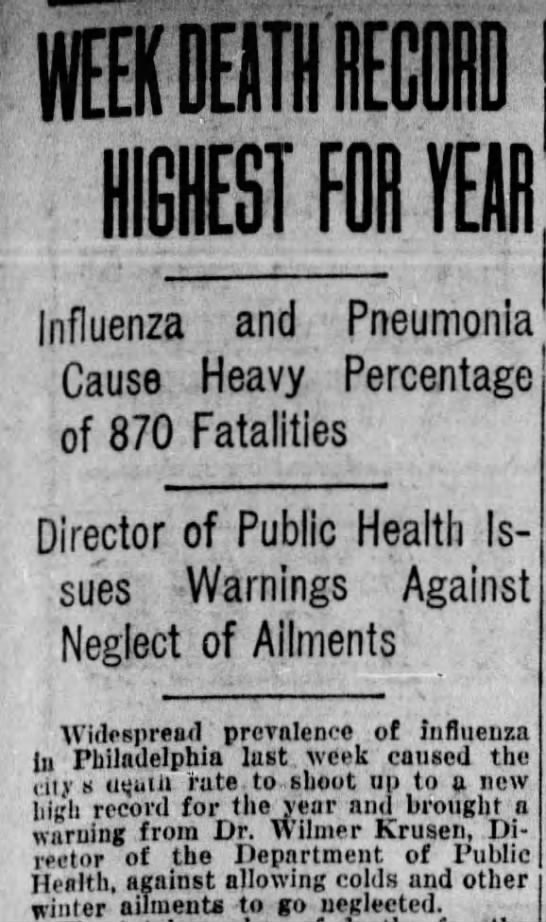

As we are all living through the social, political, and economic upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the sufferings of those who experienced epidemics of the past seem all the more real to us now, and we can begin to connect with how it feels to read the following headline from the Philadelphia Inquirer, March 7, 1926. The flu had already caused a noticeable and significant spike in the death rate.

It’s important to note that this was the fourth flu epidemic in a 10-year period. The first, and more famous, was the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic which took the lives of 16,000 Philadelphians in six months. Nearly a decade later, it must have felt like a cruel twist of fate that the flu monster had returned in a 1926 epidemic. In fact, there had been flu spikes in 1922, 1925, and 1926. The Public Health Record noted that, “In fact, were it not for the over-shadowing pandemic of 1918… the 1926 outbreak would have been regarded as a calamity.” (Public Health Report, August 20, 1926)

This was probably the same flu that attacked Rebecca and Miriam. They started to show symptoms during the second week of March. From the biography we learn that the family decided not to inform Abe that his sisters were ill. “The Doctor was on his way to England and it did not seem worthwhile bothering him about it.” (Wolf, 248)

On the evening of March 14, both sisters took a turn for the worse. It’s unclear if there was a communication to Dr. Rosenbach. Phil, however, was at his sisters’ bedside along with Dr. Solomon Solis-Cohen. The biography indicates that Rebecca had taken care of Miriam for so long that “…she was obsessed with the thought that she might die and Miriam be left to face the world alone.” And here we find a heart-breaking story where Rebecca, searching for air and probably aware that these were her last breaths, refuses to succumb until she is sure that her sister Miriam would not be left alone.

“Phillip, desperate, stood beside his sister’s bed, and, as she was visibly sinking, grasped her by the arm and said, “See here, Rebecca, you’ve got to get better.” In a whisper, his sister asked, “Is Miriam still alive?” “Yes.” Miraculously, Rebecca refused to die. That afternoon Miriam quietly passed away. Within a few hours after Miriam’s death, Rebecca understood that her responsibilities had ended. Wearily she gave up her fight.” (248)

A cable was sent to Abe. And here the biography gives a hint into a part of Abe that I had only previously intuited. “He spent his life suppressing most of his basic emotions and drinking so that he could release enough of them to feel human. When something touched his inner self as deeply and as brutally as did his sister’s death, he was shaken beyond his conscious control.” (249)

He must have rushed back because the funeral was held on March 16, only two days later. What a brutal trip that must have been. While it is customary in the Orthodox and Reformed Jewish faiths to bury the dead within 24 hours if possible, as we are finding today with the tragic COVID-19 death toll in New York city, the funeral parlors may have been overwhelmed and perhaps hesitant to provide services for potentially still contagious bodies. The funeral was held at 2006 Delancey Street; at home.

Abe’s life changed. As hinted in the biography, he may have increasingly sought solace in drink. The constant back and forth to England slowed down. He didn’t go in 1927. And he went again only two times; in 1928 and 1930. “The world, and even comparatively good friends, who thought of the Doctor as flitting back and forth across the ocean at the sound of the turning of a page, were amazed to learn that when he died, he had not been to Europe in twenty-two years.” (Wolf 249)

We all have no idea how the trauma of COVID-19 will affect us in the future. Already psychologists are describing ‘anticipatory grief,’ where we grieve now for things that we know will never be the same. The trauma of March 1926 is not something we regularly talk about during our tour; it’s a weighty subject. Personally, I don’t like perfect historical narratives – nobody has a life without sadness, grief, and loss. This story brings Abe and Phil closer. It opens up Miriam and Rebecca and allows me, and by extension visitors to the Rosenbach, to connect to real humans, who have lived real lives just like ours.

References:

Wolf, Edwin, and John F. Fleming. Rosenbach; a Biography. 1st ed., World Pub. Co, 1960.

“The Influenza Epidemic of 1926: A Preliminary Note on Certain Epidemiological Indications.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970), vol. 41, no. 34, 1926, pp. 1759–1774. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4577980.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 7, 1926.