For those of you who have seen Peter Dobrin’s recent articles

in the Philadelphia Inquirier (both Sunday‘s and Tuesday‘s), you already know that the Sendak

Collection held here on deposit since 1968 will be leaving us shortly and returning

to the Sendak Foundation in Connecticut.

Our exhibition Sendak in the ‘60s will remain on view

through its scheduled end-date, November 2, so be sure to check it out! There are some amazing pieces from Where

the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen on display, but the ‘60s

was perhaps Sendak’s most varied and inventive period so there’s something for

everyone in there.

in the Philadelphia Inquirier (both Sunday‘s and Tuesday‘s), you already know that the Sendak

Collection held here on deposit since 1968 will be leaving us shortly and returning

to the Sendak Foundation in Connecticut.

Our exhibition Sendak in the ‘60s will remain on view

through its scheduled end-date, November 2, so be sure to check it out! There are some amazing pieces from Where

the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen on display, but the ‘60s

was perhaps Sendak’s most varied and inventive period so there’s something for

everyone in there.

In the meantime, I thought I’d share some behind-the-scenes

memories and reflections of our work with Maurice Sendak over the decades. Tens of thousands of people have enjoyed

Sendak’s work through exhibitions and programs here over almost 50 years, but (at

least for those who haven’t met him) not everyone knows how generous Maurice

was with his time and insights on a personal level. He visited here often, bringing artwork with

him, speaking to docents about his work, and doing lectures and signings of his

latest books for visitors.

memories and reflections of our work with Maurice Sendak over the decades. Tens of thousands of people have enjoyed

Sendak’s work through exhibitions and programs here over almost 50 years, but (at

least for those who haven’t met him) not everyone knows how generous Maurice

was with his time and insights on a personal level. He visited here often, bringing artwork with

him, speaking to docents about his work, and doing lectures and signings of his

latest books for visitors.

|

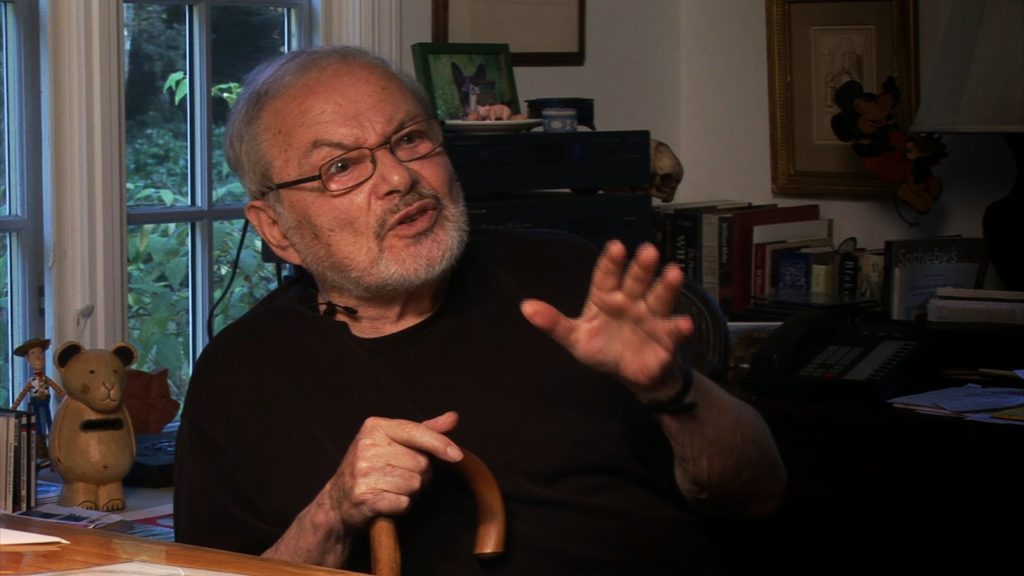

| Maurice Sendak in 2007. Photo courtesy of Michael O’Reilly. |

When we interviewed him in 2007, Sendak remembered his first

visits to the Rosenbach in the late ‘60s fondly: “I remember I would lay in Dr.

Rosenbach’s room, and they would bring me in some drawings for a French novel by Fragonard

and there was a big animal fur blanket and I used to lay under it with my

Fragonards all around. Hey—that was

living! Of course, they took it all back

in the morning.” The Rosenbach’s first big Sendak exhibition went up in 1970,

displaying much of Sendak’s work up to that point while also including works by

artists who influenced Sendak that were either borrowed from his personal

collection or from other area museums. Admission

then was $1.50. In a review in Artforum,

critic Selma Lanes (who ten years later would publish a compendious biography

of Sendak) noted how this early retrospective lifted Sendak out of the

easy-to-dismiss “kiddie-book” category to which he had often been consigned,

and placed him within a continuum of inventive illustrators: “During an era

when bold use of color, abstract design, outsize format and showy technical

virtuosity abounded, his work has always remained low-key, curiously

retrograde, and 19th-century in spirit. From the exhibited selections, made by both

the artist and Clive Driver, the Rosenbach’s young curator, Sendak clearly

emerges as a conscientious and respectful student of the past, an innovator

within a long tradition rather than a smasher of stylistic idols. As Sendak himself has put it, ‘I borrowed

techniques and tried to forge them into a personal language.’”

visits to the Rosenbach in the late ‘60s fondly: “I remember I would lay in Dr.

Rosenbach’s room, and they would bring me in some drawings for a French novel by Fragonard

and there was a big animal fur blanket and I used to lay under it with my

Fragonards all around. Hey—that was

living! Of course, they took it all back

in the morning.” The Rosenbach’s first big Sendak exhibition went up in 1970,

displaying much of Sendak’s work up to that point while also including works by

artists who influenced Sendak that were either borrowed from his personal

collection or from other area museums. Admission

then was $1.50. In a review in Artforum,

critic Selma Lanes (who ten years later would publish a compendious biography

of Sendak) noted how this early retrospective lifted Sendak out of the

easy-to-dismiss “kiddie-book” category to which he had often been consigned,

and placed him within a continuum of inventive illustrators: “During an era

when bold use of color, abstract design, outsize format and showy technical

virtuosity abounded, his work has always remained low-key, curiously

retrograde, and 19th-century in spirit. From the exhibited selections, made by both

the artist and Clive Driver, the Rosenbach’s young curator, Sendak clearly

emerges as a conscientious and respectful student of the past, an innovator

within a long tradition rather than a smasher of stylistic idols. As Sendak himself has put it, ‘I borrowed

techniques and tried to forge them into a personal language.’”

That was the first of many Sendak shows over the next four

decades. Later exhibitions would delve

into specific Sendak books (Chicken Soup with Rice or In the Night

Kitchen, for example), or investigate themes and techniques in his artwork

(such as Maurice Sendak, Comic Strip Technique, and Wilhelm Busch in

1993, or the 1986 exhibition Man’s Best Friend about Sendak’s dog

Jennie). Periodically—when a new

exhibition went up or a new Sendak book was published—Sendak would stop by and

speak with our docents. It’s rare for

educators to have access to a living artist whose work they interpret for

visitors, and we’re fortunate that past staff had the foresight to record some

of those sessions on cassette tapes. Listening

to them now, I’m struck by how earnest, warm, and excited Sendak sounded in

those conversations. You can hear him

turning the pages of his picture books as he shows the docents particular illustrations. He clearly wanted our docents to be

well-supplied with information and insights on which to chew. In one conversation he expounded on the

distinction he saw between illustrating a “picture book” (giving Where the

Wild Things Are as an example) and a “story book” (citing Higglety,

Pigglety, Pop!). He likened a

picture book to an opera, where images and texts move back and forth in a kind

of syncopation. But a story book, he

explained, must remain focused on the narrative, noting that the trick is to

add something to the pictures; he said he tried to inject a certain “emotional

coloring” to his pictures for Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Zlateh the Goat to

counterbalance Singer’s dry wit in the text.

In other conversations he comments on his fellow-illustrators, like N.C.

Wyeth (“Complicated feelings. A great

master… but he has somewhat the problem of Arthur Rackham, where he has one style,

that N.C.-Wyeth-look.”), and Dr. Seuss (“a master and a maniac…condemned to

being a best-seller”), as well as various authors like Melville (“You don’t

want [your illustrations] to get in the way of him…he’s a trumpet, a noisy

writer”), Randall Jarrell (“He was one of the few writers I’ve ever worked with

who could…visualize what a book could look like. Very few writers understand the business of

illustrating their books. They just want

nice pictures”), and Isaac Singer (“The best part of the collaboration

was him. The worst part was him”). And, of course, Sendak took many questions

from our docents about everything from his work in theater and opera to his

childhood memories and familial relationships.

decades. Later exhibitions would delve

into specific Sendak books (Chicken Soup with Rice or In the Night

Kitchen, for example), or investigate themes and techniques in his artwork

(such as Maurice Sendak, Comic Strip Technique, and Wilhelm Busch in

1993, or the 1986 exhibition Man’s Best Friend about Sendak’s dog

Jennie). Periodically—when a new

exhibition went up or a new Sendak book was published—Sendak would stop by and

speak with our docents. It’s rare for

educators to have access to a living artist whose work they interpret for

visitors, and we’re fortunate that past staff had the foresight to record some

of those sessions on cassette tapes. Listening

to them now, I’m struck by how earnest, warm, and excited Sendak sounded in

those conversations. You can hear him

turning the pages of his picture books as he shows the docents particular illustrations. He clearly wanted our docents to be

well-supplied with information and insights on which to chew. In one conversation he expounded on the

distinction he saw between illustrating a “picture book” (giving Where the

Wild Things Are as an example) and a “story book” (citing Higglety,

Pigglety, Pop!). He likened a

picture book to an opera, where images and texts move back and forth in a kind

of syncopation. But a story book, he

explained, must remain focused on the narrative, noting that the trick is to

add something to the pictures; he said he tried to inject a certain “emotional

coloring” to his pictures for Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Zlateh the Goat to

counterbalance Singer’s dry wit in the text.

In other conversations he comments on his fellow-illustrators, like N.C.

Wyeth (“Complicated feelings. A great

master… but he has somewhat the problem of Arthur Rackham, where he has one style,

that N.C.-Wyeth-look.”), and Dr. Seuss (“a master and a maniac…condemned to

being a best-seller”), as well as various authors like Melville (“You don’t

want [your illustrations] to get in the way of him…he’s a trumpet, a noisy

writer”), Randall Jarrell (“He was one of the few writers I’ve ever worked with

who could…visualize what a book could look like. Very few writers understand the business of

illustrating their books. They just want

nice pictures”), and Isaac Singer (“The best part of the collaboration

was him. The worst part was him”). And, of course, Sendak took many questions

from our docents about everything from his work in theater and opera to his

childhood memories and familial relationships.

The bulk of Sendak’s artwork might be leaving the Rosenbach,

but so much remains. The authors and

illustrators in our permanent collection that so inspired him (Dickinson,

Melville, Carroll, Tenniel, Blake…) will still be here to inspire others. The Rosenbach still owns a few hundred pieces of

Sendak artwork, including the one-of-a-kind Chertoff mural, which is an

inspiration of itself. But perhaps most

importantly, the perspectives on art and literature that Sendak shared with

staff, docents, and visitors here have unquestionably left their mark on this

institution.

but so much remains. The authors and

illustrators in our permanent collection that so inspired him (Dickinson,

Melville, Carroll, Tenniel, Blake…) will still be here to inspire others. The Rosenbach still owns a few hundred pieces of

Sendak artwork, including the one-of-a-kind Chertoff mural, which is an

inspiration of itself. But perhaps most

importantly, the perspectives on art and literature that Sendak shared with

staff, docents, and visitors here have unquestionably left their mark on this

institution.

Patrick Rodgers is Curator of the Maurice Sendak Collection at the Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia.