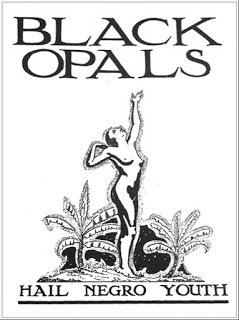

On February 9, poets Yolanda Wisher and Dick Lourie will co-host a program at the Rosenbach entitled Blues for Black Opals. Published between 1927 and 1928, Black Opals was a Philadelphia-based literary magazine founded and edited by young black intellectuals and writers. Blues for Black Opals will celebrate the poetry from that era of social change, merging past and present with readings from poets Quincy Scott Jones, Iréne Mathieu, and Trapeta Mayson, and performances with musicians Jim Dragoni, Sirlance Gamble, and Mark Palacio.

Rosen-blog: How did you first learn about the literary magazine Black Opals?

Yolanda Wisher: A few years ago, I was doing research on Black poets in 19th and 20th century Philadelphia and came across a sentence or two about the Black Opals Collective online. I learned that there were original copies of the magazine in the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University. So I went to pay my respects and makes copies of my favorite poems.

RB: How did the two of you get started collaborating on creative projects?

YW: Dick edited my first book of poems at Hanging Loose Press in 2014. I thought it was just perfect that a blues musician was going to be my editor. We had a lot of great conversations about language and music on the phone as edited the book together. I learned a lot from him about how to put a book together. Afterwards Dick suggested that we do a gig together. I was, of course, ecstatic about that! Our first time performing together was at the Philalalia Festival this past September 2016 at the Institute of Contemporary Art.

Dick Lourie: Hanging Loose, the magazine and small press I started with three other poets fifty years ago (no wonder I feel tired) is always on the lookout for interesting and exciting poets. Along comes Yolanda; we starting having her poems in our magazine, and then about four years ago we were eager to publish her book, Monk Eats an Afro. As her editor, I worked with Yolanda closely by phone and email—editing a book always involves some degree of author/editor collaboration—and we soon discovered a shared creative interest in poetry / music performance. At some point in there we actually laid eyes on each other, and kept talking about performing together, which we did last fall—spoken word, song, chant, trumpet, saxophone, and Yolanda’s wonderful band the Afro Eaters. We had more fun than we deserved, and we decided we should keep it up. So I’m grateful to the Rosenbach for giving us another chance.

RB: You are both known for musical performance as well as for your poetry. How does music inform your poetry, or vice versa?

DL: I write in syllabics—no regular meter, no rhyme, but the same number of syllables in every line (in my case, ten). Thus each line is of roughly the same length, although the spoken rhythm of each is unique. And the music I play, mostly, is the blues, a musical form structured usually in twelve-measure choruses, 4/4 time (four equal beats to each measure). At a certain point I started to realize that each line of a poem could be spoken to fit into one measure of a blues chorus. I began speaking the poems with blues band accompaniment and adding sax or trumpet solos that seemed to fit the mood of the poem. That all seemed to work, so I have kept at it. And those performances kept my mind on music, and on the tradition of the blues, so a number of my poems now are written about blues music, its history, its culture.

YW: Writing poetry is like composing a kind of music with words. And musical performance is a way to share the force of the creative process and to feel it evolve in the presence of an audience.

RB: I know it’s hard to choose a favorite, but what is one literary or musical piece from next Thursday’s performance that you are particularly excited to share?

DL: I hope we will be again performing one of Yolanda’s pieces, “Cornrow Song,” that we did together in the fall. It’s contemporary in form and idiom, and at the same time takes us all the way back in history (to Babylon…) and on from there, and in Yolanda’s performance, with music, it moves along like a soulful time machine. On the page as well, it is special—that’s why she and I decided it should be the final poem in the book, traditionally a place of honor that sums up the whole achievement. (And besides, in the performance I get to play a trumpet solo).

YW: I’m excited to hear Irène, Trapeta, and Quincy read the work of Black Opals poets like Walter Waring, Edward S. Silvera II, Nellie R. Bright, Bessie Calhoun Bird, and Lewis Alexander. It will be exciting to witness a younger generation of Black poets getting acquainted with these literary ancestors.

RB: What have you read recently that sparked your imagination or admiration?

DL: What I’ve been reading recently are Langston Hughes’s “Simple” stories, about Jesse B. Semple, nicknamed Simple, a 1940s–50s Harlem man on the street. These are lively, funny yet gritty, tales of a particular time period and a particular community. The original stories were part of Hughes’s column in the Chicago Defender, an important African American newspaper of the time. They were later collected, and new ones written. They remain a fascinating look from the inside at the Harlem of that period.

RB: What’s your favorite book or object at the Rosenbach?

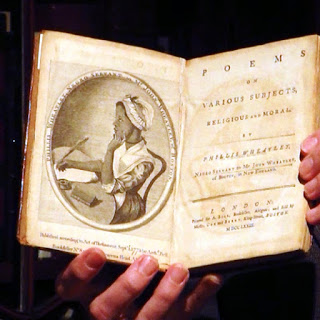

YW: I held Phillis Wheatley’s first collection of poems in my hands the first time I visited the Rosenbach a year ago. It gave me goosebumps! Wheatley was one of my first influences and someone whose life holds enough triumph and mysteries to keep me forever intrigued and rapt. That book is like an amulet or holy grail of African American literature. It was a sacred moment to hold it in my hands.